“In light of what we now know regarding wrongful prosecution and conviction rates in this country, we must face the harsh reality that our criminal justice system is not just fallible,” Rudolf writes, with a book’s worth of examples to back up his claim. “It suffers from systemic, inherent faults and abuses of power by police and prosecutors — abuses of power that routinely produce erroneous convictions of innocent people.”

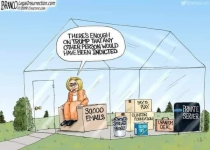

Leave aside this action by the Biden justice department — and for that matter, any number of examples from the Trump and Obama and Bush and Clinton justice departments. When criminal justice loses its credibility — due to a decades-long parade of wrongful convictions and a litany of politically-motivated prosecutions — all that is left is a power struggle between various players. And no player is more powerful than the government.

Canadians are inclined to see the excesses of the American justice system and think we are better off. That’s likely true, but cold comfort. It may be because we just know less about how our system works.

Decades of police and prosecutorial abuses have demonstrated that it is right for us to be suspicious

apple.news

This is not about the past. Just this week Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino told a House of Commons committee that the

RCMP employs spyware — collecting data from devices, turning on mobile phone microphones or cameras — but it is used sparingly and with judicial approval.

Why would anyone believe him? The minister was spectacularly wrong when he claimed that the police had asked for the Emergencies Act to be invoked, suspending basic civil liberties and invading personal privacy. He was either

Mendacious Marco or Misunderstood Mendicino, but in either case he was not telling the truth.

If the RCMP was truly desirous of protecting Canadian liberties, it may have run its spyware by the privacy commissioner first, not leaving him to read about the program in the papers.

“It would be preferable, far preferable, that privacy impact assessment be done at the front end, that my office be consulted and that this can be conveyed somehow to Canadians so that they are reassured,” Privacy Commissioner Philippe Dufresne told MPs.

We have recently watched the spectacle of the RCMP commissioner, Brenda Lucki,

insisting that she “did not interfere in the ongoing investigations into the largest mass shooting in Canadian history.” Her own subordinates claim she did just that to advance the political agenda of the Liberal government.

It’s possible that Merrick Garland is not telling the truth about the Trump raid, which he may have ordered for political purposes. It is certainly plausible that Donald Trump is not telling the truth. And we see the consequences.

Our situation is also dire. Many — including me — do not believe the denials of our public safety minister and Canada’s top cop that politics was not decisive in criminal justice matters of the most grave importance. We do not believe them because their claims are simply not believable.

And because decades of police and prosecutorial abuses have demonstrated that it is right to be suspicious.