🍁Happy Tariff Day🍁

- Thread starter B00Mer

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

But but but Dutch Elm Disease. If Liberals dont fuck the dollar Ontario auto parts will suffer.Canada already has a 35% advanage with the Canadian dollar being so low, it would not have hurt us to wait, rather than Trudeau with his hatred for Trump go all Rambo with retaliatory Tariffs and playing this up like a Liberal win. It's not.

Dutch Disease

Remarks

Mark Carney

Spruce Meadows Round Table

Calgary, Alberta

September 7, 2012

Introduction

Some regard Canada’s wealth of natural resources as a blessing. Others see it as a curse.

The latter look at the global commodity boom and make the grim diagnosis for Canada of “Dutch Disease.” 1 They dismiss the enormous benefits, including higher incomes and greater economic security, our bountiful natural resources can provide.

Their argument goes as follows: record-high commodity prices have led to an appreciation of Canada’s exchange rate, which, in turn, is crowding out trade-sensitive sectors, particularly manufacturing. The disease is the notion that an ephemeral boom in one sector causes permanent losses in others, in a dynamic that is net harmful for the Canadian economy.

While the tidiness of the argument is appealing and making commodities the scapegoat is tempting, the diagnosis is overly simplistic and, in the end, wrong. Canada’s economy is much more diverse and much better integrated than the Dutch Disease caricature. Numerous factors influence our currency and, most fundamentally, higher commodity prices are unambiguously good for Canada.

That is not to trivialise the difficult structural adjustments that higher commodity prices can bring. Nor is it to suggest a purely laissez-faire response. Policy can help to minimise adjustment costs and maximise the benefits that arise from commodity booms, but like any treatment, it is more likely to be successful if the original diagnosis is correct.

The Global Outlook

The global economy is experiencing a broad-based deceleration from an already modest pace.

A New Normal for the United States

The U.S. recovery is following the same dreary path of other advanced economies that have experienced financial crises. GDP growth has averaged just 2.2 per cent since the trough in 2009. Indeed, it is only with justified comparisons to the Great Depression that the success of the U.S. policy response is apparent.

The only good news is that some progress on repairing balance sheets is being made.

U.S. banks have substantially increased their capital (common equity to total assets is up by more than 25 per cent). American households have recovered more than two-thirds of the $16 trillion fall in their net worth in the aftermath of the crisis, though we estimate that it will take several more years for households to make up the balance.

Despite this, total debt in America has barely fallen from its peak of 250 per cent of GDP-a level last seen in the Great Depression. This is because U.S. government debt has increased $4 for every $1 reduction of household debt. Such treading water will persist for some time since private domestic demand is still not sufficiently robust to outweigh an aggressive fiscal tightening.

Bottom line, with less capital investment and more structural unemployment, the Bank estimates that the U.S. economy will remain over $1 trillion smaller in 2015 than we had projected prior to the crisis (Chart 1).

Even in this room, that is a big number.

An Existential Crisis in Europe

Europe is stagnating with GDP still 2 per cent below its pre-crisis peak and private domestic demand a stunning 6 per cent below. A tough combination of fiscal austerity and structural adjustment will mean falling wages, high unemployment and tight credit conditions. As a consequence, Europe is unlikely to return to its pre-crisis level of GDP until a full seven years after the start of its last recession.

Given ties of trade, finance and confidence, the rest of the world is feeling the effects.

Europe’s contraction is driving banking losses and fiscal shortfalls. But these challenges are merely symptoms of an underlying sickness: a balance of payments crisis.

To repay the creditors in the core, the debtors of the periphery must regain competitiveness. This will be neither easy nor quick.

The burden cannot solely be on increasing unemployment and reducing wages in countries like Spain. An increase in German wages (and inflation) would ease the transition, especially if the structural reforms now under way across the deficit countries actually boost productivity.

Important measures have been announced over the summer to begin to restore the single financial market, break the toxic links between banks and sovereigns and, potentially, help ensure that all euro-area countries can finance at more sustainable rates.

All of these measures need to be fully implemented, not just announced. In that regard, the Bank very much welcomes yesterday’s announcement by the European Central Bank (ECB) of significant new measures to address convertibility risk and improve the transmission of monetary policy. However, it will take some time to restore market confidence, and it will take years for fiscal and structural adjustments to work. Moreover, the discussions over the federal institutions that may be ultimately required to support a durable monetary union are still in their infancy.

Emerging-Market Economies

In China and other emerging economies, the deceleration in growth in recent months has been greater than anticipated, reflecting past policy tightening, weaker external demand and the challenges of rebalancing to domestic sources of growth.

Real GDP in China grew 7.6 per cent in the second quarter-the slowest pace in three years. Recent data suggest continued softening in this quarter.

In part, this reflects a welcome policy-induced slowdown from the increasingly unsustainable rates of growth in recent years. With large vulnerabilities building in the housing sector, evidence of overinvestment increasing, and inflation above target, Chinese policy-makers appropriately responded by tightening monetary and macroprudential policies.

Less anticipated has been the extent to which weaker external demand, especially from Europe, has weighed on export growth.

More recently, in light of slowing growth and moderating price pressures, the People’s Bank of China has eased monetary policy and the fiscal stance has been relaxed. In both regards, authorities retain considerable additional policy flexibility. The Bank of Canada expects Chinese growth to average about 7.5 per cent over the next few years, materially below the unsustainable double digit rates seen since the trough of the crisis.

More

Dutch Disease

Governor Mark Carney discusses the impact of high commodity prices for the Canadian economy.

This 10% Tariff on Canadian Oil is only a temporary, and soon will be 25% in a year. Trump still needs our crude, for now but added a 10% to appease US Oil Companies and Associations.

Right now in Texas and Louisiana companies are looking for ways to ramp up production to freeze out Canadian heavy crude with Texas sweet crude from the USA.

They are even attacking Canada's US investments which could have drastic implications on Canada's CCP. 6 Canadian projects that Trudeau invested in (Green Projects of course) are in pearl which could cost Canadians and our CCP billions of dollars.

This is very hush, hush.. CBC and CTV won't let you know.

Canada is so fucked right now..

Right now in Texas and Louisiana companies are looking for ways to ramp up production to freeze out Canadian heavy crude with Texas sweet crude from the USA.

They are even attacking Canada's US investments which could have drastic implications on Canada's CCP. 6 Canadian projects that Trudeau invested in (Green Projects of course) are in pearl which could cost Canadians and our CCP billions of dollars.

This is very hush, hush.. CBC and CTV won't let you know.

Canada is so fucked right now..

The president of Venezuela has more sense than Justin Trudeau!

So I guess Mexico's part of the tariff's is on pause a month because they "made an agreement".

At this point, believing Trump on anything is a dangerous game.

At this point, believing Trump on anything is a dangerous game.

A lot of ripped-off investors would question "At this point. . ."So I guess Mexico's part of the tariff's is on pause a month because they "made an agreement".

At this point, believing Trump on anything is a dangerous game.

So I guess Mexico's part of the tariff's is on pause a month because they "made an agreement".

At this point, believing Trump on anything is a dangerous game.

Thank Gawd..

Trudeau and Doug Ford were tossing Mexico under the bus a month ago...

I like President Sheinbaum,

Shes smart, really cares about her people.. we need more leaders like her in this world.

Don't know why she was even in communication with Trudeau or working with Canada regarding these tariffs.

Claudia Sheinbaum - Wikipedia

Last edited:

Only a partial deal with Mexico deploying 10,000 troops to the border.Thank Gawd..

Trudeau and Doug Ford were tossing Mexico under the bus a month ago...

View attachment 27275

I like President Sheinbaum,

Shes smart, really cares about her people.. we need more leaders like her in this world.

Don't know why she was even in communication with Trudeau or working with Canada regarding these tariffs.

Claudia Sheinbaum - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Trump doesn't want to deal with the Liberals. Poilievre should handling this not a fucking retarded fruitcake.

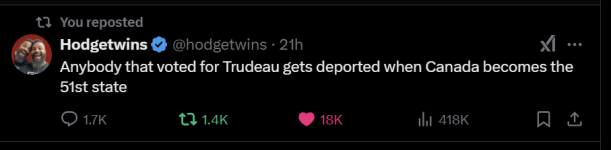

Some of the tweets though, priceless.

View attachment 27270

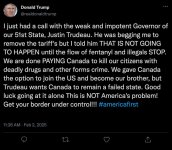

Just went out and purchased some Florida Orange juice, Kentucky Bourbon and a plane ticket to Arizona to leave this arctic tundra wasteland.

View attachment 27271

G'bye then, traitor, no one will miss you.

Only a partial deal with Mexico deploying 10,000 troops to the border.

Trump doesn't want to deal with the Liberals. Poilievre should handling this not a fucking retarded fruitcake.

Yeah no kidding, meanwhile Premiers are making it difficult to remove the tariffs because they are each imposing regional tariffs.

US Citizens are also getting nasty towards Canadians in this tariff war..

One Yankee was saying close the border, we don't want anything from that Socialist shithole.

My reply was polite, "well I guess you're going to starve to death.. 90% of your potash to fertilize your crops come from Canada.

I guess after your all dead, we can just move in and claim you as the 11th Province."

One Yankee was saying close the border, we don't want anything from that Socialist shithole.

My reply was polite, "well I guess you're going to starve to death.. 90% of your potash to fertilize your crops come from Canada.

I guess after your all dead, we can just move in and claim you as the 11th Province."

I can't believe there are people that still vote Liberal in this country..

ElectionsYeah no kidding, meanwhile Premiers are making it difficult to remove the tariffs because they are each imposing regional tariffs.

So we're 'on hold' like Mexico and outside of a border czar, there wasn't anything new said that could be added to before this crap happened.

So I guess Trump failed.

So I guess Trump failed.