Fortunes spent on plastic shields with no proof they stop COVID-19

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Carey Goldberg

Publishing date:Jun 08, 2021 • 18 hours ago • 4 minute read • Join the conversation

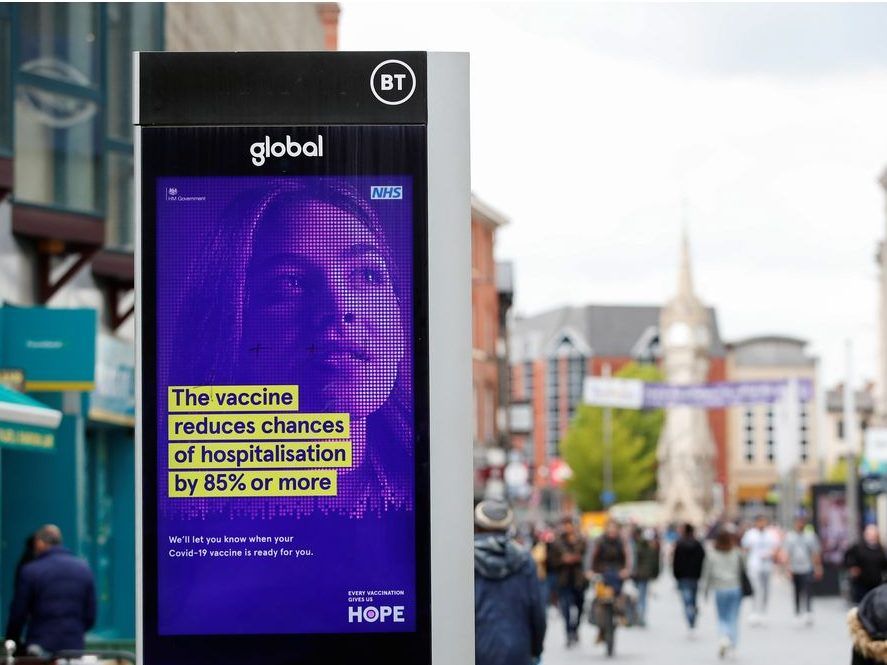

Israeli Yeshiva (Jewish educational institution for studies of traditional religious texts) students are picture at their learning centre separated by plastic barriers to insure that social distancing measures imposed by Israeli authorities meant to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus are being respected, in Tel Aviv on July 7, 2020.

Israeli Yeshiva (Jewish educational institution for studies of traditional religious texts) students are picture at their learning centre separated by plastic barriers to insure that social distancing measures imposed by Israeli authorities meant to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus are being respected, in Tel Aviv on July 7, 2020. PHOTO BY GIL COHEN-MAGEN /AFP via Getty Images

Article content

(Bloomberg) — Everybody wanted them: Sales of clear plastic dividers soared in the U.S. after the pandemic hit — tripling year-over-year to roughly $750 million in the first quarter of last year, by industry estimates.

Offices, schools, restaurants and retail stores all sought plexiglass protection from the droplets that health authorities suspected were spreading the coronavirus.

How to increase confidence when buying a used car

Trackerdslogo

There was just one hitch. Not a single study has shown that plastic barriers in places like schools and offices actually control the virus, said Joseph Allen of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“We spent a lot of time and money focused on hygiene theater,” said Allen, an indoor-air researcher. “The danger is that we didn’t deploy the resources to address the real threat, which was airborne transmission — both real dollars, but also time and attention.”

“The tide has turned,” he said. “The problem is, it took a year.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

For the first months of Covid-19, top health authorities pointed to larger droplets as the key transmission culprits, despite a chorus of protests from researchers like Allen. Tinier floating droplets can also spread the virus, they warned, meaning plastic shields can’t stop them. Not until last month did the World Health Organization and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fully affirm airborne transmission.

That meant plastic shielding had created “a false sense of security,” said building scientist Marwa Zaatari, a pandemic task force member of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

“Especially when we use it in offices or in schools specifically, plexiglass does not help,” Zaatari said. “If you have plexiglass, you’re still breathing the same shared air of another person.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Recent CDC research found that desk or table barriers in Georgia elementary schools didn’t correlate with lower infection rates. Mask mandates and ventilation improvements did.

An April study published by the journal Science suggested that desk shields might even slightly raise the risk of Covid-like symptoms. And a prepublication paper from Japan late last month linked plastic shielding with infections in a poorly ventilated office.

Such studies raise the ironic possibility that when venues install too much plastic and impede ventilation, they could be raising the very risk they’re trying to reduce.

Err Apparent

Last fall, a coronavirus outbreak swept through the main office of Wellesley High School in suburban Boston, despite preventive measures that included clear plastic barriers around work stations.

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

When school and health officials puffed smoke into the work stations to analyze air flow, they found that it lingered and swirled instead of ascending to ceiling filters. “The smoke just kind of hung out. It didn’t move as you would expect it to move,” said Superintendent David Lussier.

The investigation concluded that among other factors, the plexiglass side panels around desks seemed to increase the risk of virus transmission by blocking air flow. The side panels were removed, even though “I wouldn’t want anyone to believe plexiglass doesn’t help, because we still use plexiglass,” Lussier said. “As a barrier it can be, and is, helpful.”

Hospital infection-fighters also still support plastic shields. Epidemiologist Shira Doron at Tufts Medical Center in Boston acknowledged that “there’s no research” to support plexiglass barriers against coronavirus spread. “We don’t know a lot,” she said. But one tenet of infection prevention, she said, boils down to, “If it might help, and it makes sense, and it doesn’t hurt, then do it.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Doron acknowledged that “you could have a situation where plexiglass impedes ventilation” and has the opposite of its intended effect. “But it has not been scientifically proven to be correlated with transmission,” she said.

Allen and Zaatari acknowledge that plastic makes sense in certain limited settings: in front of a cashier who faces many people at close range through the workday, for instance, as long as the shields don’t block needed air flow.

But they maintain that for schools and offices, money has been best spent on improved ventilation and air filtration, along with masks.

Improvements to air also carry benefits beyond Covid, Allen said: “They’re good for seasonal influenza. They’re good for productivity. They’re good for mental health.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

The widespread tendency to put up plastic “cascades from the original misguidance on droplets,” he said.

Harvard Business School senior lecturer John Macomber pointed to other factors that fueled the shield boom: Plastic hoods were known to fight germs at salad bars. They were relatively cheap and likely to be within the budget and control of an individual office tenant or school facility manager. They were highly visible — and reassuring.

“Sort of like taking our shoes off at the airport,” said Macomber, who has 30 years of experience in construction and real estate. “Or hotels where they put the piece of paper around the toilet seat to show the maid has been there. Businesses try to signal they’ve done something, but that something isn’t necessarily very deep.”

With U.S. case numbers dropping, so are some plastic shields, according to scattered reports from restaurants, gyms and casinos. If current trends continue, building scientist Zaatari believes it will take only “a matter of weeks to remove all the plexiglass. The question is what they’re going to do with it.” ”

There’s good news on that front, said Craig Saunders, president of the International Association of Plastics Distribution:

“It’s 100% recyclable thermoplastic,” he said. It “just comes down to the logistics” of gathering it up and shipping it off for a post-pandemic second life.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Carey Goldberg

Publishing date:Jun 08, 2021 • 18 hours ago • 4 minute read • Join the conversation

Israeli Yeshiva (Jewish educational institution for studies of traditional religious texts) students are picture at their learning centre separated by plastic barriers to insure that social distancing measures imposed by Israeli authorities meant to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus are being respected, in Tel Aviv on July 7, 2020.

Israeli Yeshiva (Jewish educational institution for studies of traditional religious texts) students are picture at their learning centre separated by plastic barriers to insure that social distancing measures imposed by Israeli authorities meant to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus are being respected, in Tel Aviv on July 7, 2020. PHOTO BY GIL COHEN-MAGEN /AFP via Getty Images

Article content

(Bloomberg) — Everybody wanted them: Sales of clear plastic dividers soared in the U.S. after the pandemic hit — tripling year-over-year to roughly $750 million in the first quarter of last year, by industry estimates.

Offices, schools, restaurants and retail stores all sought plexiglass protection from the droplets that health authorities suspected were spreading the coronavirus.

How to increase confidence when buying a used car

Trackerdslogo

There was just one hitch. Not a single study has shown that plastic barriers in places like schools and offices actually control the virus, said Joseph Allen of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“We spent a lot of time and money focused on hygiene theater,” said Allen, an indoor-air researcher. “The danger is that we didn’t deploy the resources to address the real threat, which was airborne transmission — both real dollars, but also time and attention.”

“The tide has turned,” he said. “The problem is, it took a year.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

For the first months of Covid-19, top health authorities pointed to larger droplets as the key transmission culprits, despite a chorus of protests from researchers like Allen. Tinier floating droplets can also spread the virus, they warned, meaning plastic shields can’t stop them. Not until last month did the World Health Organization and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fully affirm airborne transmission.

That meant plastic shielding had created “a false sense of security,” said building scientist Marwa Zaatari, a pandemic task force member of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

“Especially when we use it in offices or in schools specifically, plexiglass does not help,” Zaatari said. “If you have plexiglass, you’re still breathing the same shared air of another person.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Recent CDC research found that desk or table barriers in Georgia elementary schools didn’t correlate with lower infection rates. Mask mandates and ventilation improvements did.

An April study published by the journal Science suggested that desk shields might even slightly raise the risk of Covid-like symptoms. And a prepublication paper from Japan late last month linked plastic shielding with infections in a poorly ventilated office.

Such studies raise the ironic possibility that when venues install too much plastic and impede ventilation, they could be raising the very risk they’re trying to reduce.

Err Apparent

Last fall, a coronavirus outbreak swept through the main office of Wellesley High School in suburban Boston, despite preventive measures that included clear plastic barriers around work stations.

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

When school and health officials puffed smoke into the work stations to analyze air flow, they found that it lingered and swirled instead of ascending to ceiling filters. “The smoke just kind of hung out. It didn’t move as you would expect it to move,” said Superintendent David Lussier.

The investigation concluded that among other factors, the plexiglass side panels around desks seemed to increase the risk of virus transmission by blocking air flow. The side panels were removed, even though “I wouldn’t want anyone to believe plexiglass doesn’t help, because we still use plexiglass,” Lussier said. “As a barrier it can be, and is, helpful.”

Hospital infection-fighters also still support plastic shields. Epidemiologist Shira Doron at Tufts Medical Center in Boston acknowledged that “there’s no research” to support plexiglass barriers against coronavirus spread. “We don’t know a lot,” she said. But one tenet of infection prevention, she said, boils down to, “If it might help, and it makes sense, and it doesn’t hurt, then do it.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Doron acknowledged that “you could have a situation where plexiglass impedes ventilation” and has the opposite of its intended effect. “But it has not been scientifically proven to be correlated with transmission,” she said.

Allen and Zaatari acknowledge that plastic makes sense in certain limited settings: in front of a cashier who faces many people at close range through the workday, for instance, as long as the shields don’t block needed air flow.

But they maintain that for schools and offices, money has been best spent on improved ventilation and air filtration, along with masks.

Improvements to air also carry benefits beyond Covid, Allen said: “They’re good for seasonal influenza. They’re good for productivity. They’re good for mental health.”

Advertisement

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

The widespread tendency to put up plastic “cascades from the original misguidance on droplets,” he said.

Harvard Business School senior lecturer John Macomber pointed to other factors that fueled the shield boom: Plastic hoods were known to fight germs at salad bars. They were relatively cheap and likely to be within the budget and control of an individual office tenant or school facility manager. They were highly visible — and reassuring.

“Sort of like taking our shoes off at the airport,” said Macomber, who has 30 years of experience in construction and real estate. “Or hotels where they put the piece of paper around the toilet seat to show the maid has been there. Businesses try to signal they’ve done something, but that something isn’t necessarily very deep.”

With U.S. case numbers dropping, so are some plastic shields, according to scattered reports from restaurants, gyms and casinos. If current trends continue, building scientist Zaatari believes it will take only “a matter of weeks to remove all the plexiglass. The question is what they’re going to do with it.” ”

There’s good news on that front, said Craig Saunders, president of the International Association of Plastics Distribution:

“It’s 100% recyclable thermoplastic,” he said. It “just comes down to the logistics” of gathering it up and shipping it off for a post-pandemic second life.

Fortunes spent on plastic shields with no proof they stop COVID-19

(Bloomberg) — Everybody wanted them: Sales of clear plastic dividers soared in the U.S. after the pandemic hit — tripling year-over-year to roughly $750 million in …