The constant refusal of some CC members to accept technological change got me to wondering about how many other society changing inventions were condemned at the time of their inception. Well, it turns out that there are quite a few. Here are seven of the more important.

7 world-changing inventions people thought were dumb fads

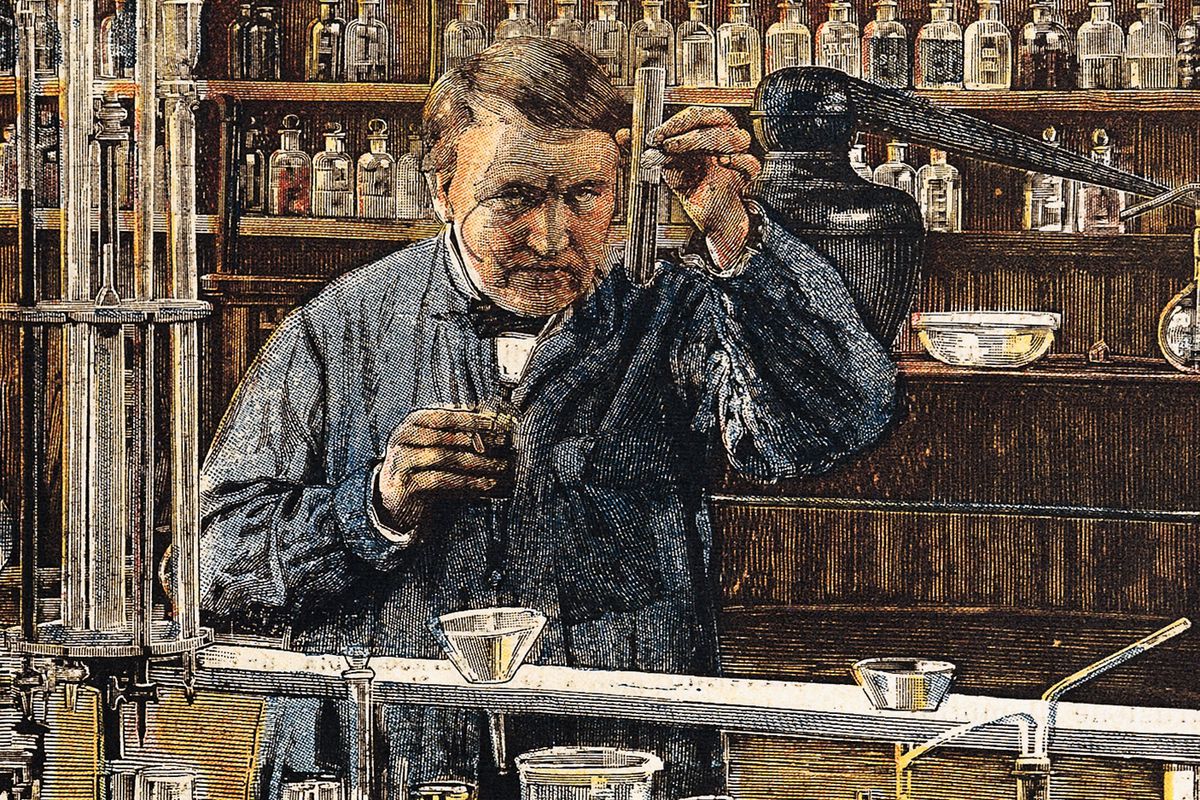

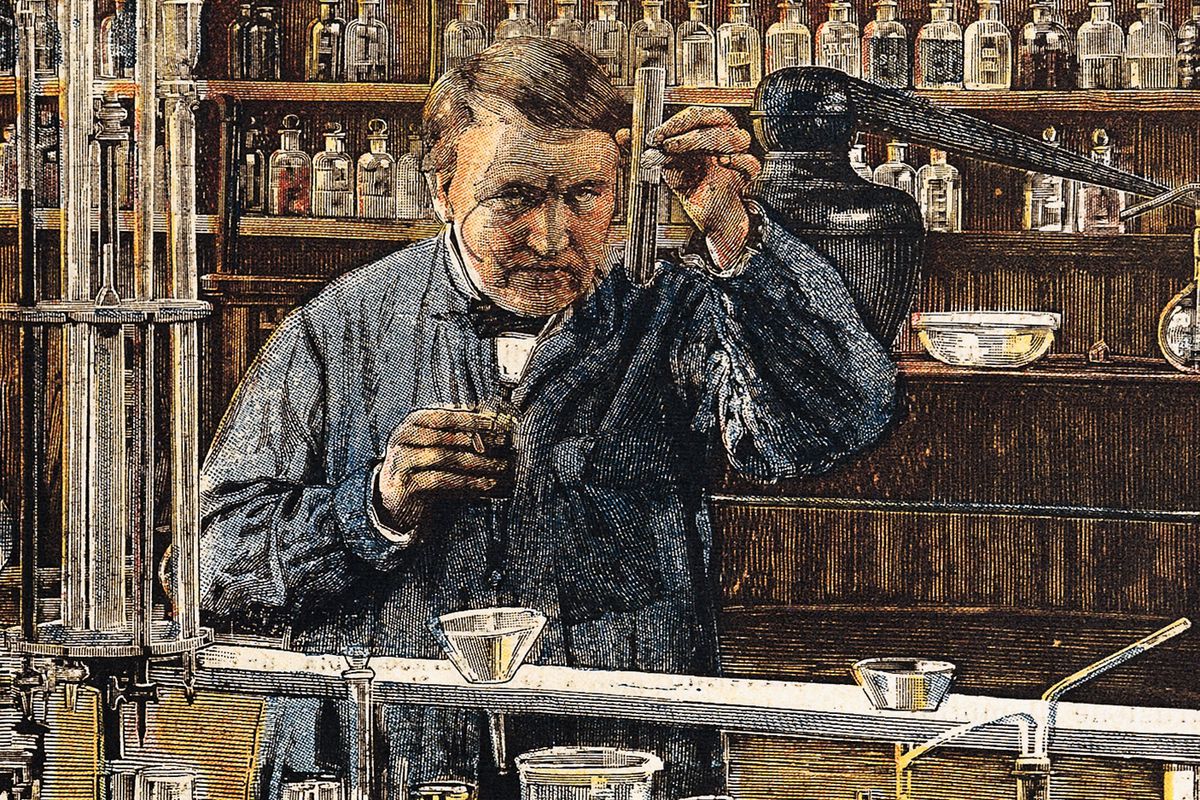

In 1879, Henry Morton, a leading scientific mind and president of the Stevens Institute of Technology, called one man's tinkering a "conspicuous failure." The man was Thomas Edison. The invention was the light bulb.

That was obviously wrong, and the light bulb turned out to be a solid invention. But Morton's statement was also revealing. Sometimes it's genuinely difficult to know whether new inventions will be duds or hits. Who knows — maybe our grandkids will come to love Google Glass, Segways, and Dippin' Dots.

Related These 7 inventions were supposed to change the world. They failed. Badly.

Morton's pronouncement shows just how hard it is to predict the future. In his case, he didn't doubt that Edison's lightbulb was useful. His main objection was that there was no way to carry electricity long distances and get light bulbs in every home (even Edison couldn't figure that out on his own.) Forecasting the fate of a new invention often means forecasting broad social and technological changes — and that's incredibly hard.

With that in mind, here's a look at seven other important inventions — from the bicycle to nail polish to the answering machine — that had their doubters early on. There's a lot to learn from wrong predictions:

1) Bicycles: "The popularity of the wheel is doomed"

Critical mass, 1890s-style. (Leemage/Getty Images)

Critical mass, 1890s-style. (Leemage/Getty Images)

Today, we think of bikes as a major source of transportation, but they started out as a trendy fashion statement. That's why some critics were skeptical that they'd stick around (spoiler: they did).

Bikes had a rapid rise: on August 20, 1890, the Washington Post called bicycling a hot fad for fancy ladies and not just for the "bleached-haired, music-hall type" anymore (read: hipsters). The craze was driven by improved technology, as big-wheeled bikes became closer to the ones we use today. The bicycle's growth was so rapid that on February 29, 1896, the Washington Post called bicycling the national sport.

But then the fad faded. On August 17, 1902, the Post called bicycling a passing fancy, and experts declared "the popularity of the wheel is doomed." Critics thought bikes were unsafe, impossible to improve, and ultimately impractical for everyday use. On December 31, 1906, the New York Sun rendered its verdict: "As a fad cycling is dead, and few individuals now ride for all the good they claim to see in the pastime when it was fashion."

The Sun turned out to be wrong. Over the years, bikes acquired better tires, and sturdier frame. America's roads also got smoother. That made bicycles an increasingly practical option — and not just a passing fad.

2) Automobiles: "The prices will never be sufficiently low"

An early automobile racer. (New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

An early automobile racer. (New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

In 1902, the New York Times called the automobile impractical — and they had a few good reasons why. In the wake of the bike fad of the 1890s, reporters and analysts were wary of the "next big thing" in transportation. As one critic put it:

But it did. Once Henry Ford perfected the mass production of automobiles, the price came down and cars took off, eventually becoming the dominant form of transportation.

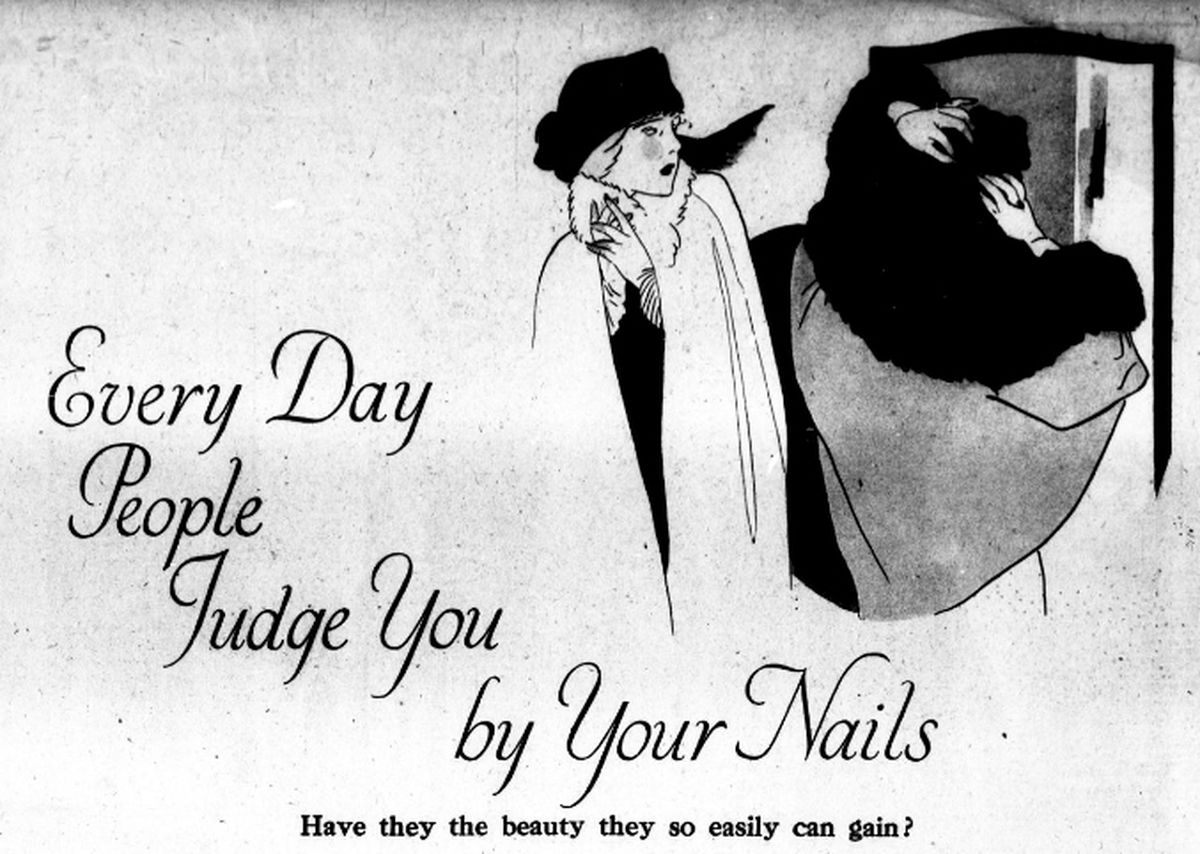

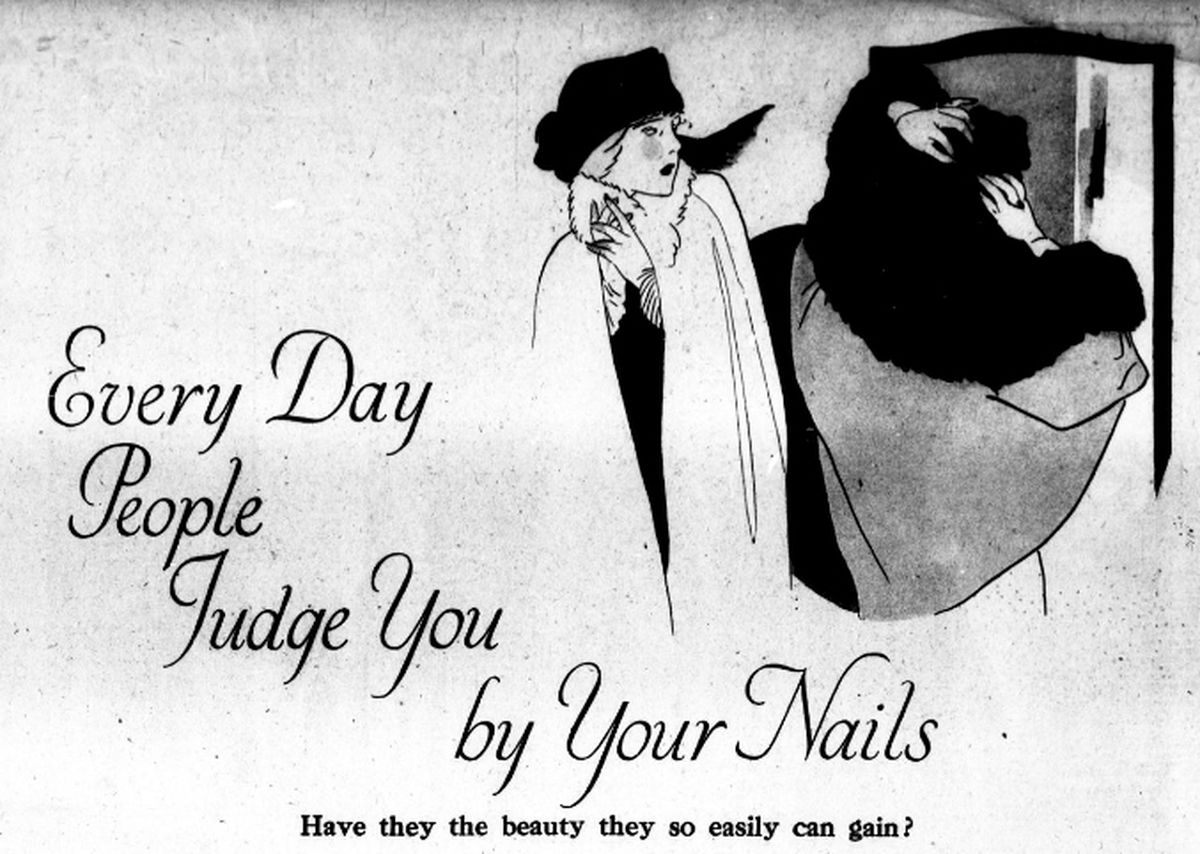

3) Liquid nail polish was a "strange and unique fad"

Nail polish shame: where it began. (Library of Congress)

Nail polish shame: where it began. (Library of Congress)

In 1917, Cutex invented the closest thing to modern mass-market liquid nail polish. But it took a while for nail polish to hit the mainstream. In 1927, the New York Times reported on it as a "London fad," and the year before, writer Viola Paris took to the pages of Vogue to assess the new invention. "There seems to be some doubt," she wrote, "in the minds of a great many women as to whether nail polish is in any way harmful or, at least, not so good for the nails as the powder or paste polish."

As late as March 31, 1932, the Atlanta Daily World questioned how long colored fingernails could possibly stick around. "Dame fashion, whimsical and wayward as the wind," the paper snarked, "has so many strange and unique fads that her latest vagary, that of tinting the fingernails...has become quite popular."

Ultimately, nail polish wasn't just a passing fancy. Better manufacturing processes, a new age of mass marketing, and clear advantages over powders and pastes helped it stick around.

4) Talkies: "Talking doesn't belong in pictures"

Joseph Schenck, pondering the future, silently. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Joseph Schenck, pondering the future, silently. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1928, Joseph Schenck, President of United Artists, seemed confident about one thing: talking pictures were a fad.

He told The New York Times that "talking doesn't belong in pictures." Though he conceded that sound effects could be useful, he felt that dialogue was overrated. "I don't think people will want talking pictures long," he said, and he wasn't alone.

In 1967, actress Mary Astor recalled the mood when the silent era drew to a close. She wrote, "The Jazz Singer was considered a box-office freak," and that talkies were "a box-office gimmick." In an early talkie screening, she and her colleagues thought "the noise would simply drive audiences from the theaters... we were in an entirely different medium."

In the end, however, talkies proved out to be more compelling than the old mediums. Audiences adjusted, audio-recording technology improved, and a new generation of Hollywood bigwigs embraced dialogue.

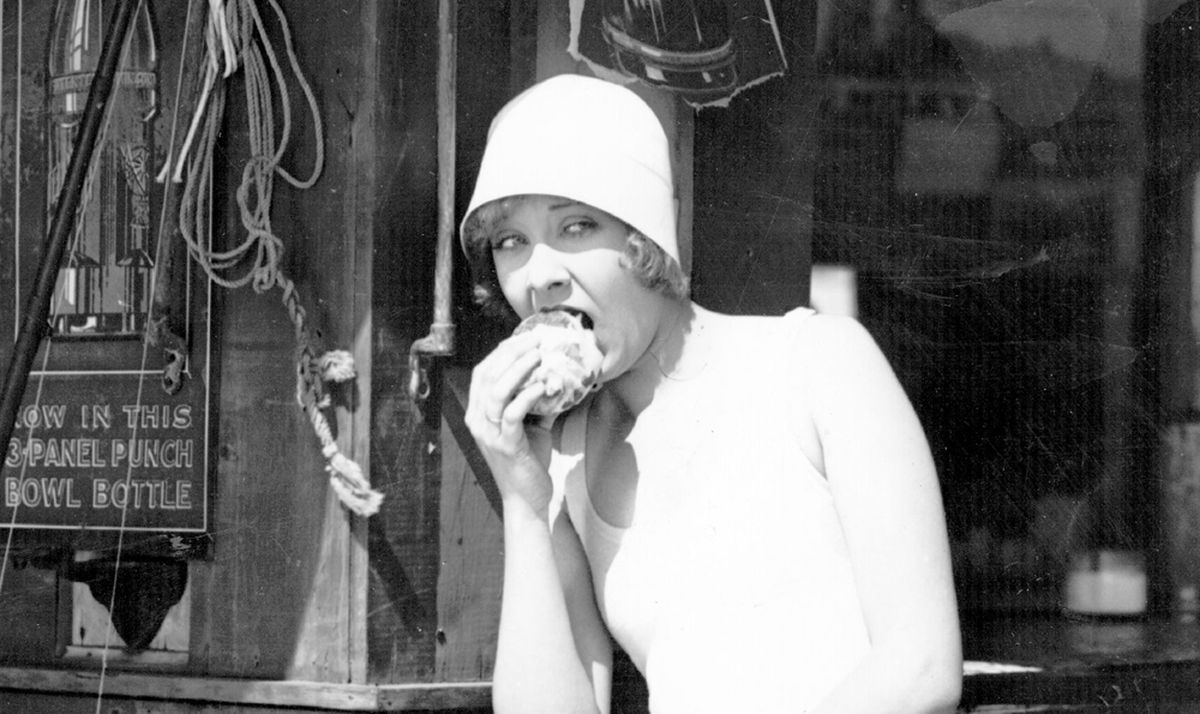

5) Cheeseburgers: "Typical of California"

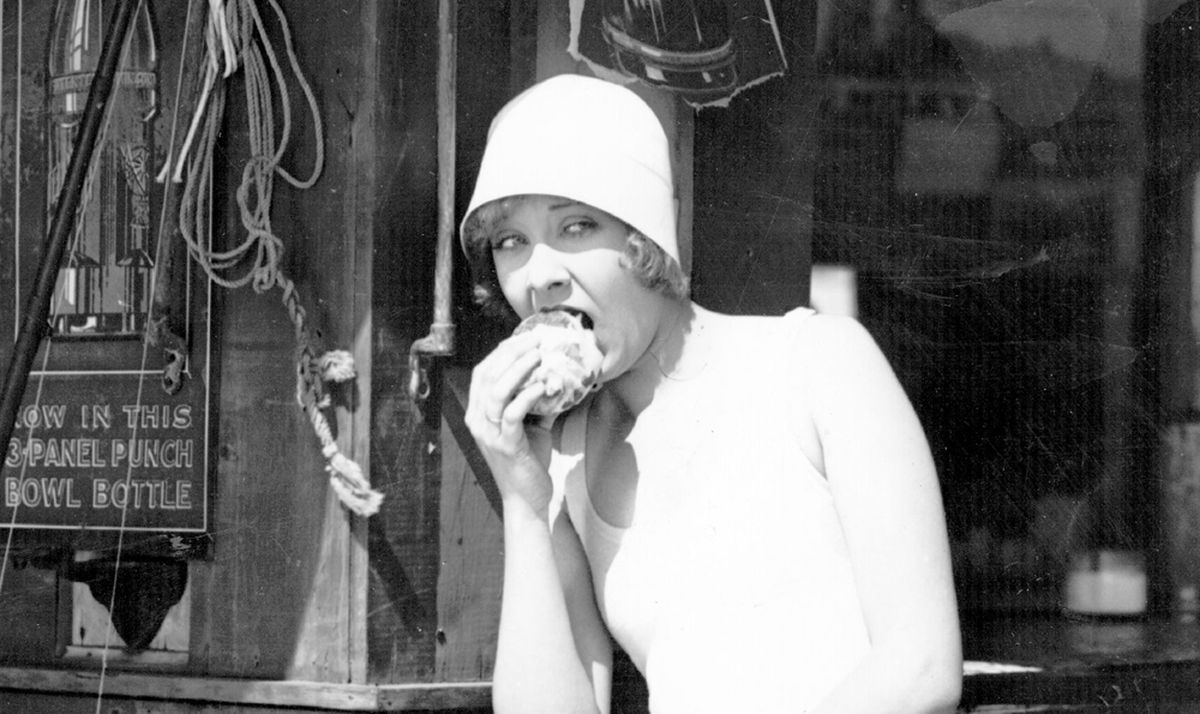

Actress Gwen Lee eats a burger in California in 1930. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Actress Gwen Lee eats a burger in California in 1930. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Most sources credit Lionel Sternberger with inventing the cheeseburger in 1934, though there's a lot of debate. Regardless of who came up with it, the notion of beef and cheese was initially regarded as a crazy California novelty rather than as a revelation.

The first time the New York Times wrote about cheeseburgers in 1938, they ranked the burgers as a Californian eccentricity, putting them third in a list along with nutburgers, porkburgers, and turkeyburgers. In 1947, a Times writer actually deigned to try a cheeseburger, albeit skeptically:

6) Answering machines: "In the beginning, it was pure yuppie."

In 1970, this machine was slick. (Science and Society Picture Library/Getty Images)

In 1970, this machine was slick. (Science and Society Picture Library/Getty Images)

It didn't take long for people to see how answering machines could be useful. But when they were first introduced, it seemed like the telephone companies would squash them in favor of their own hardware and services.

In 1973, a story about the bourgeoning voicemail phenomenon noted that answering machines weren't even allowed in most homes. Robert Howard, a spokesman for the New York Telephone Company, claimed that illegally installed machines posed a hazard to line repairmen. Since the 1940s, most companies had banned them, and AT&T said "there is no need for the device."

Even once answering machines moved from quasi-legal purgatory in 1975, thanks to an FCC decision, the devices were still seen as a niche yuppie annoyance. That might be why it took until 1991 for the New York Times to reluctantly accept answering machines with a telling headline: "For Yuppies, Now Plain Folks Too."

The answering machine made it big because technology, laws, and telephone culture changed. Answering-machine technology became easier to manage and answering services faded away.

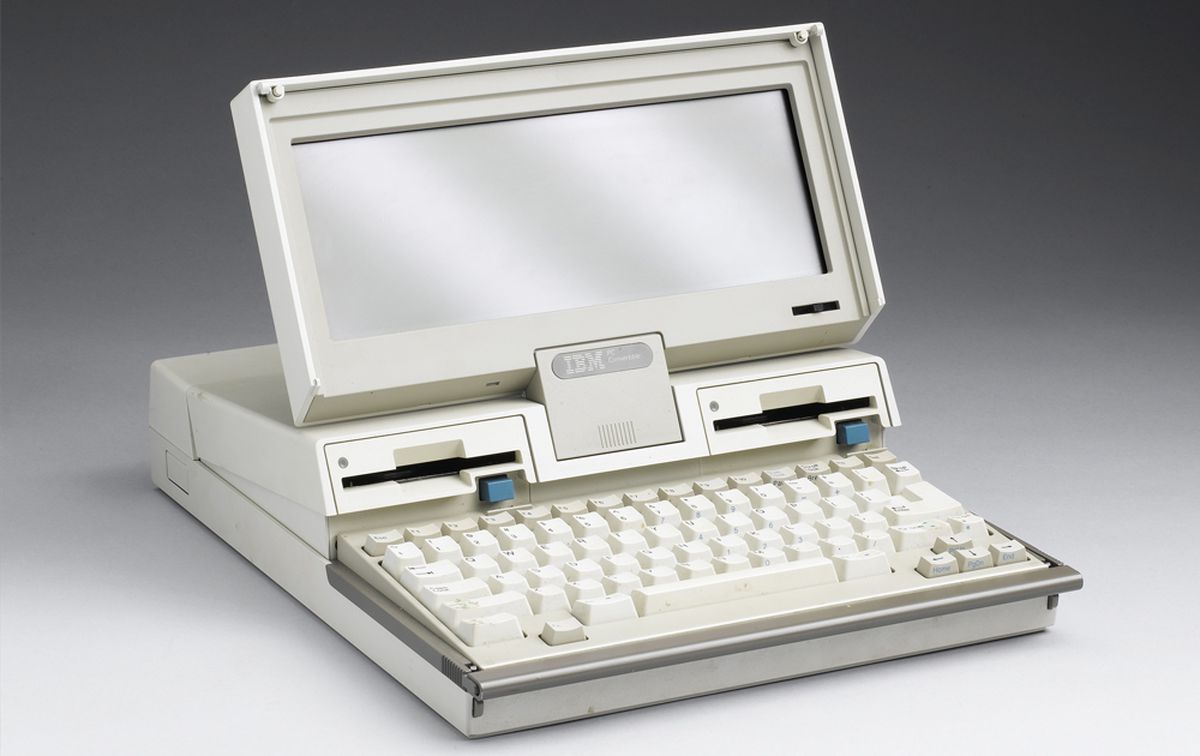

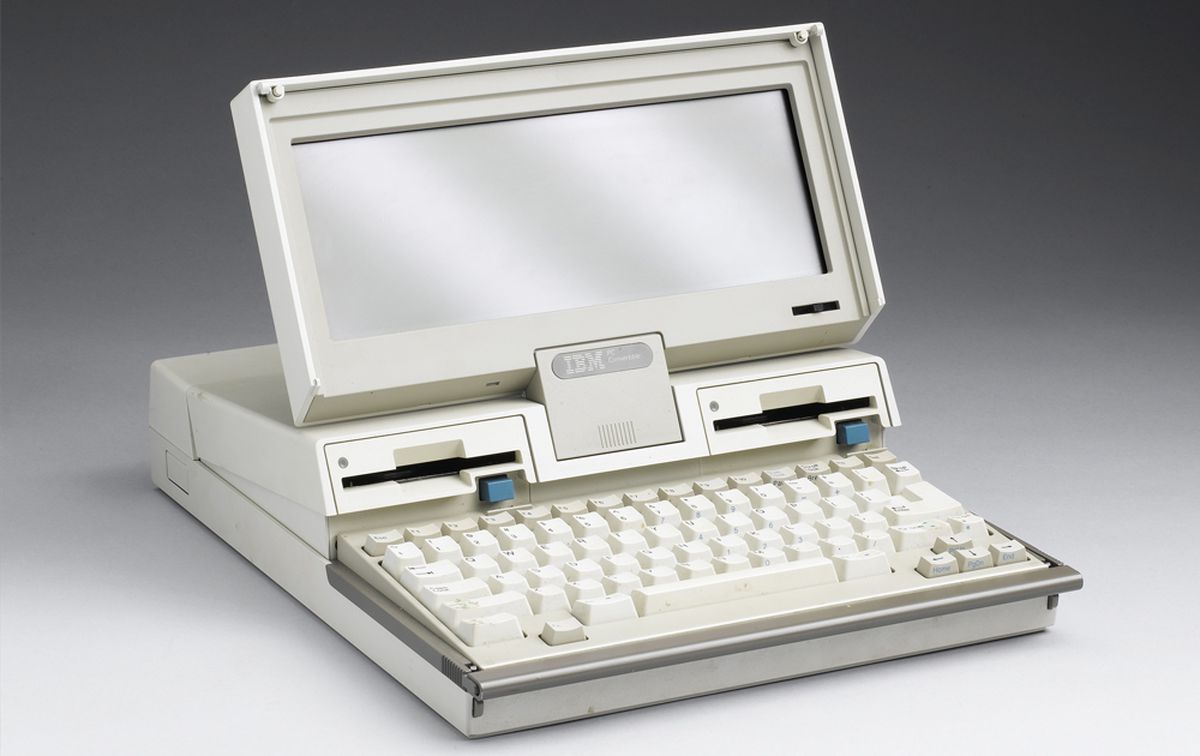

7) Laptops: "Was the laptop dream an illusion?"

1987's laptops were a work in progress. (Science and Society Archive/Getty Images)

1987's laptops were a work in progress. (Science and Society Archive/Getty Images)

In 1985, the New York Times reported on the tragic demise of a once promising trend — laptops, the newspaper said, were on their way out. From now on, airplane tray tables would hold beers and cocktails instead of computers.

The Times doubted the potential of laptop technology, and with good reason: they were heavy, pricey, and had poor battery life, all of which made it hard to imagine them becoming mainstream.

It was a reasonable complaint, but short-sighted:

7 world-changing inventions people thought were dumb fads

In 1879, Henry Morton, a leading scientific mind and president of the Stevens Institute of Technology, called one man's tinkering a "conspicuous failure." The man was Thomas Edison. The invention was the light bulb.

That was obviously wrong, and the light bulb turned out to be a solid invention. But Morton's statement was also revealing. Sometimes it's genuinely difficult to know whether new inventions will be duds or hits. Who knows — maybe our grandkids will come to love Google Glass, Segways, and Dippin' Dots.

Related These 7 inventions were supposed to change the world. They failed. Badly.

Morton's pronouncement shows just how hard it is to predict the future. In his case, he didn't doubt that Edison's lightbulb was useful. His main objection was that there was no way to carry electricity long distances and get light bulbs in every home (even Edison couldn't figure that out on his own.) Forecasting the fate of a new invention often means forecasting broad social and technological changes — and that's incredibly hard.

With that in mind, here's a look at seven other important inventions — from the bicycle to nail polish to the answering machine — that had their doubters early on. There's a lot to learn from wrong predictions:

1) Bicycles: "The popularity of the wheel is doomed"

Today, we think of bikes as a major source of transportation, but they started out as a trendy fashion statement. That's why some critics were skeptical that they'd stick around (spoiler: they did).

Bikes had a rapid rise: on August 20, 1890, the Washington Post called bicycling a hot fad for fancy ladies and not just for the "bleached-haired, music-hall type" anymore (read: hipsters). The craze was driven by improved technology, as big-wheeled bikes became closer to the ones we use today. The bicycle's growth was so rapid that on February 29, 1896, the Washington Post called bicycling the national sport.

But then the fad faded. On August 17, 1902, the Post called bicycling a passing fancy, and experts declared "the popularity of the wheel is doomed." Critics thought bikes were unsafe, impossible to improve, and ultimately impractical for everyday use. On December 31, 1906, the New York Sun rendered its verdict: "As a fad cycling is dead, and few individuals now ride for all the good they claim to see in the pastime when it was fashion."

The Sun turned out to be wrong. Over the years, bikes acquired better tires, and sturdier frame. America's roads also got smoother. That made bicycles an increasingly practical option — and not just a passing fad.

2) Automobiles: "The prices will never be sufficiently low"

In 1902, the New York Times called the automobile impractical — and they had a few good reasons why. In the wake of the bike fad of the 1890s, reporters and analysts were wary of the "next big thing" in transportation. As one critic put it:

Automobiling is following the history of cycling with such remarkable closeness in almost every detail, both as a sport and an industry, that the question is often asked if the present period of expansion will be followed by a collapse as complete and as disastrous as was that of the cycling boom of a few short years ago.

The Times complained that the price of cars "will never be sufficiently low to make them as widely popular as were bicycles." It didn't help that some of the early proposals for an auto-centric transportation system were outlandish. In 1902, The Steel Roads Committee of the Automobile Club of America was angling for a steel highway system. Bizarre proposals like that made it harder to believe the car would ever make it big.

But it did. Once Henry Ford perfected the mass production of automobiles, the price came down and cars took off, eventually becoming the dominant form of transportation.

3) Liquid nail polish was a "strange and unique fad"

In 1917, Cutex invented the closest thing to modern mass-market liquid nail polish. But it took a while for nail polish to hit the mainstream. In 1927, the New York Times reported on it as a "London fad," and the year before, writer Viola Paris took to the pages of Vogue to assess the new invention. "There seems to be some doubt," she wrote, "in the minds of a great many women as to whether nail polish is in any way harmful or, at least, not so good for the nails as the powder or paste polish."

As late as March 31, 1932, the Atlanta Daily World questioned how long colored fingernails could possibly stick around. "Dame fashion, whimsical and wayward as the wind," the paper snarked, "has so many strange and unique fads that her latest vagary, that of tinting the fingernails...has become quite popular."

Ultimately, nail polish wasn't just a passing fancy. Better manufacturing processes, a new age of mass marketing, and clear advantages over powders and pastes helped it stick around.

4) Talkies: "Talking doesn't belong in pictures"

In 1928, Joseph Schenck, President of United Artists, seemed confident about one thing: talking pictures were a fad.

He told The New York Times that "talking doesn't belong in pictures." Though he conceded that sound effects could be useful, he felt that dialogue was overrated. "I don't think people will want talking pictures long," he said, and he wasn't alone.

In 1967, actress Mary Astor recalled the mood when the silent era drew to a close. She wrote, "The Jazz Singer was considered a box-office freak," and that talkies were "a box-office gimmick." In an early talkie screening, she and her colleagues thought "the noise would simply drive audiences from the theaters... we were in an entirely different medium."

In the end, however, talkies proved out to be more compelling than the old mediums. Audiences adjusted, audio-recording technology improved, and a new generation of Hollywood bigwigs embraced dialogue.

5) Cheeseburgers: "Typical of California"

Most sources credit Lionel Sternberger with inventing the cheeseburger in 1934, though there's a lot of debate. Regardless of who came up with it, the notion of beef and cheese was initially regarded as a crazy California novelty rather than as a revelation.

The first time the New York Times wrote about cheeseburgers in 1938, they ranked the burgers as a Californian eccentricity, putting them third in a list along with nutburgers, porkburgers, and turkeyburgers. In 1947, a Times writer actually deigned to try a cheeseburger, albeit skeptically:

At first, the combination of beef with cheese and tomatoes, which are sometimes used, may seem bizarre. If you reflect a bit, you'll understand that the combination is sound gastronomically.

[FONT=Alright Sans, sans-serif]In the end, plenty of people agreed that the cheeseburger was "sound gastronomically." And once fast food chains — like McDonald's — included it on their menus, it was guaranteed a place on the American plate.[/FONT]

6) Answering machines: "In the beginning, it was pure yuppie."

It didn't take long for people to see how answering machines could be useful. But when they were first introduced, it seemed like the telephone companies would squash them in favor of their own hardware and services.

In 1973, a story about the bourgeoning voicemail phenomenon noted that answering machines weren't even allowed in most homes. Robert Howard, a spokesman for the New York Telephone Company, claimed that illegally installed machines posed a hazard to line repairmen. Since the 1940s, most companies had banned them, and AT&T said "there is no need for the device."

Even once answering machines moved from quasi-legal purgatory in 1975, thanks to an FCC decision, the devices were still seen as a niche yuppie annoyance. That might be why it took until 1991 for the New York Times to reluctantly accept answering machines with a telling headline: "For Yuppies, Now Plain Folks Too."

The answering machine made it big because technology, laws, and telephone culture changed. Answering-machine technology became easier to manage and answering services faded away.

7) Laptops: "Was the laptop dream an illusion?"

In 1985, the New York Times reported on the tragic demise of a once promising trend — laptops, the newspaper said, were on their way out. From now on, airplane tray tables would hold beers and cocktails instead of computers.

The Times doubted the potential of laptop technology, and with good reason: they were heavy, pricey, and had poor battery life, all of which made it hard to imagine them becoming mainstream.

It was a reasonable complaint, but short-sighted:

The limitations come from what people actually do with computers, as opposed to what the marketers expect them to do. On the whole, people don't want to lug a computer with them to the beach or on a train to while away hours they would rather spend reading the sports or business section of the newspaper. Somehow, the microcomputer industry has assumed that everyone would love to have a keyboard grafted on as an extension of their fingers. It just is not so.

Laptops took a few more years to become practical, but technology improved enough that the laptop became lighter, more durable, and easier to use.