I also did not realize I had a regional accent until text to talk either. Well, not much of one anyway.

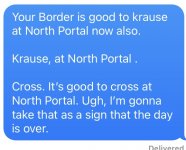

I know from having in-laws in Utah that we in Saskatchewan generally speak about half the speed that they do, but just the way we pronounce certain words really messes up text to talk. There’s a handful of words where we verbally substitute “n” for “m” creating completely different words when it’s actually written out, etc…or the “c” sound as a “p” sound, etc…

I’m not even all that bad either (regional accent, I mean) due to my exposure to a whole bunch of accents being in logistics, but it’s still there.

PS, when somebody from Utah is really excited they can speak about four times the speed of somebody from Saskatchewan, with what to us, sounds like a perfect pronunciation and diction, except after a short amount of time, it makes our heads hurt.

I know from having in-laws in Utah that we in Saskatchewan generally speak about half the speed that they do, but just the way we pronounce certain words really messes up text to talk. There’s a handful of words where we verbally substitute “n” for “m” creating completely different words when it’s actually written out, etc…or the “c” sound as a “p” sound, etc…

I’m not even all that bad either (regional accent, I mean) due to my exposure to a whole bunch of accents being in logistics, but it’s still there.

PS, when somebody from Utah is really excited they can speak about four times the speed of somebody from Saskatchewan, with what to us, sounds like a perfect pronunciation and diction, except after a short amount of time, it makes our heads hurt.