Apparently they don't understand what the word "toxic" means which is why so many people object to the law. Plastics in & of themselves are not toxic unless ingested or altered in some way (burned?). It's one thing to object to said plastics from getting into the oceans & rivers, it's another to say it's "toxic" when in actual fact it's not.Feds to appeal court ruling that struck down cabinet order labelling plastics toxic

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Mia Rabson

Published Nov 20, 2023 • 2 minute read

Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault says the federal government will appeal a Federal Court ruling which struck down a cabinet order which underlies Ottawa's ban of some single-use plastics.

Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault says the federal government will appeal a Federal Court ruling which struck down a cabinet order which underlies Ottawa's ban of some single-use plastics.

OTTAWA — The federal government will appeal a recent Federal Court ruling that struck down a cabinet order underlying Ottawa’s ban of some single-use plastics, Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said Monday.

The Nov. 16 decision said Ottawa had overstepped by labelling all “plastic manufactured items” as toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act.

Evidence shows “thousands” of different items in that category have different uses and chemical makeups, and there is no evidence all of them can harm human health or the environment, Justice Angela Furlanetto found.

The ruling itself did not undo the government’s ban on the manufacture and import of six single-use plastics — stir sticks, straws, grocery bags, cutlery, takeout containers and six-pack beverage rings.

The designation of toxicity is necessary for the government to regulate substances, however, so without it the federal regulations would have to be rolled back.

Guilbeault said he’s determined to make sure that doesn’t happen.

“The body of scientific evidence showing the impacts on human health, on the environment, of plastic pollution is undebatable,” he said.

The government has been taking steps to eliminate plastic waste by 2030, aiming to take items that are difficult to recycle out of existence entirely, while making sure the rest are recyclable or reusable.

The existing ban on manufacturing most impacted items went into effect in December 2022, with plans to prohibit their sale next month. The manufacture of six-pack rings was banned in June, with their sale to be banned in June 2024.

The court challenge was brought by the Responsible Plastic Use Coalition, which represents plastics companies that do business in Canada, and three chemical companies that produce the materials.

The coalition has said it is “supportive” of the judge’s decision.

“In the interest of Canadians who rely on plastic products that are essential to everyday life, we believe that the federal government and industry can work collaboratively to reduce plastic waste,” it said in a statement.

Some municipalities and provinces have implemented their own bans on plastics, including P.E.I. and B.C. Provincial policies are not impacted by the ruling.

Furlanetto’s decision left room for the government to ban just the items it wants by designating individual items as toxic, rather than manufactured plastic items as a whole.

The government chose those six items to ban, said Guilbeault, because they have alternatives on the market already and are among the most prevalent. They generally represent just three per cent of plastic waste.

In 2019 a Canadian report on plastics said over three million tonnes of plastic is thrown away each year and less than one-tenth of it is actually recycled.

Feds to appeal court ruling that struck down cabinet order labelling plastics toxic

The decision said Ottawa had overstepped by labelling all "plastic manufactured items" as toxic.torontosun.com

Science & Environment

- Thread starter socratus

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

I remember as a kid on lsd one time we got together to watch a... what we called then a 'japanese candle' which we set up in buddy's bedroom (his parents were out) turn out the lights...Apparently they don't understand what the word "toxic" means which is why so many people object to the law. Plastics in & of themselves are not toxic unless ingested or altered in some way (burned?). It's one thing to object to said plastics from getting into the oceans & rivers, it's another to say it's "toxic" when in actual fact it's not.

ok, it was just a green garbage bag with a string of tight knots in it, so it would burn slow enough so the plastic would melt in flame and drip, making this zip, zip, zip noise as it dripped into... I forget.. a metal waste bucket below, maybe... so you had the sound effect with the trails from the flaming drips... lol

well we probably should have done that outside, as it wasn't long before the room filled up with plastic smoke...

so that was a little god-awful ... but! it didn't kill me... and! I turned out pretty normal, didn't I?

>8?/

well???

DIDN'T I??????

8?o

ok, rhetorical question

[we never had this discussion]

:?D

The first time I did acid I was a little Leary.I remember as a kid on lsd one time

One person dead, 63 confirmed cases in salmonella outbreak linked to cantaloupe: PHAC

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Published Nov 26, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 1 minute read

The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

OTTAWA — The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

An update from the agency posted on Friday offered no details on the person who died, but says there have been 63 confirmed salmonella cases linked to the outbreak and seventeen people hospitalized.

The agency issued food recall warnings three times in November for Malichita cantaloupes sold between October 11 and November 14.

On November 24, it updated its warning to include Rudy brand cantaloupes sold between October 10 and November 24.

The cantaloupes were distributed across the country, and the agency says confirmed salmonella cases have been identified in five provinces so far: Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island. .

It says it’s investigating other potential cases and notes the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are also probing a salmonella outbreak linked to cantaloupes they describe as being the same genetic strain as the one in Canada. U.S. health officials said two people had died and 45 people were hospitalized nationwide due to the outbreak as of Friday

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Published Nov 26, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 1 minute read

The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

OTTAWA — The Public Health Agency of Canada says one person has died after a salmonella outbreak linked to Malichita and Rudy brand cantaloupes.

An update from the agency posted on Friday offered no details on the person who died, but says there have been 63 confirmed salmonella cases linked to the outbreak and seventeen people hospitalized.

The agency issued food recall warnings three times in November for Malichita cantaloupes sold between October 11 and November 14.

On November 24, it updated its warning to include Rudy brand cantaloupes sold between October 10 and November 24.

The cantaloupes were distributed across the country, and the agency says confirmed salmonella cases have been identified in five provinces so far: Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island. .

It says it’s investigating other potential cases and notes the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are also probing a salmonella outbreak linked to cantaloupes they describe as being the same genetic strain as the one in Canada. U.S. health officials said two people had died and 45 people were hospitalized nationwide due to the outbreak as of Friday

One person dead, 63 confirmed cases in salmonella outbreak linked to cantaloupe: PHAC

An update from the agency posted on Friday offered no details on the person who died, but says there have been 63 confirmed salmonella cases

Cannabis use may raise risk of heart failure, strokes and heart attacks: Studies

The two studies were done in the U.S.

Author of the article:Jane Stevenson

Published Nov 26, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 3 minute read

Regular cannabis use may raise the risk for heart failure, stroke or heart attack, according to two preliminary studies done in the U.S.

The All of Us Research Program focused on the relationship between lifestyle, biology and environment in diverse populations and analyzed the association between daily marijuana use and heart failure.

Lead study author Dr. Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, a resident physician at Medstar Health in Baltimore, followed 156,999 individuals who were free from heart failure at the time they enrolled for nearly four years.

The analysis, which was adjusted to account for individual demographic and economic factors, alcohol use, smoking and other cardiovascular risk factors linked with heart failure, found 2,958 people or almost 2% developed heart failure.

“I think many people have shown that there’s an association between cannabis and heart disease in small case studies where you have a group of patients,” said Dr. Mark Chandy, Barnett-Ivey Heart and Stroke Chair at Western University in London.

“But now we’re getting very, very high quality evidence from the epidemiological field, they’re showing in large populations of patients — as we’re seeing with the legalization of cannabis, more and more people are using it (because) of less restriction — and as a result of that we’re starting to see more adverse events such as heart disease and heart failure.”

The first study also found that people who reported daily marijuana use had a 34% increased risk of developing heart failure (a weakening of the heart to the point it can’t pump blood), compared to those who reported never using marijuana.

In a second U.S. study, researchers evaluated data from the 2019 National Inpatient Sample — the largest nationwide database of hospitalizations — to investigate whether hospital stays were complicated by a cardiovascular event, including heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest or arrhythmia, in patients who used marijuana.

Researchers used records of adults older than age 65 years with cardiovascular risk factors who reported no tobacco use, and divided them into marijuana users and non-marijuana users.

The study found of the 28,535 cannabis users with existing cardiovascular risk factors (high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes or high cholesterol), 20% had an increased chance of having a major heart or brain event while hospitalized, compared to the group who did not use cannabis.

George Smitherman, president and CEO of the Cannabis Council of Canada — representing more than 30 licensed producers and processors of cannabis products, said both studies were helpful.

“I thought it was very, very valuable data in so far is it re-enforces something that is sometimes, I believe, missed which is that no one should associate cannabis consumption, perhaps best in that combusted form, as being benign,” said Smitherman.

“And I think the studies in that context were important and beneficial. There’s a high proportion of cannabis consumers in the recreational marketplace that associate their consumption with wellness, and that’s excellent, but we need to be eyes wide open.”

The second study also found 13.9% of cannabis users with cardiovascular risk factors had a major adverse heart and brain event while hospitalized compared to non-cannabis users.

Additionally, the cannabis users in comparison to non-cannabis users had a higher rate of heart attacks (7.6% versus 6%, respectively) and were more likely to be transferred to other facilities (28.9% vs. 19%).

Smitherman said he hopes the U.S. studies will have an impact on Canadian health policy going forward, with regard to the five-year-old Cannabis Act.

“I’m just about to turn 60 and through legalization there’s been no public health messaging to me through the public health agency or anyone to say, ‘Hey, daily user of cannabis have you thought about maybe getting your THC other than through your lungs,’” he said. People can consume THC by such means as ingesting edibles, and oils.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

The two studies were done in the U.S.

Author of the article:Jane Stevenson

Published Nov 26, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 3 minute read

Regular cannabis use may raise the risk for heart failure, stroke or heart attack, according to two preliminary studies done in the U.S.

The All of Us Research Program focused on the relationship between lifestyle, biology and environment in diverse populations and analyzed the association between daily marijuana use and heart failure.

Lead study author Dr. Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, a resident physician at Medstar Health in Baltimore, followed 156,999 individuals who were free from heart failure at the time they enrolled for nearly four years.

The analysis, which was adjusted to account for individual demographic and economic factors, alcohol use, smoking and other cardiovascular risk factors linked with heart failure, found 2,958 people or almost 2% developed heart failure.

“I think many people have shown that there’s an association between cannabis and heart disease in small case studies where you have a group of patients,” said Dr. Mark Chandy, Barnett-Ivey Heart and Stroke Chair at Western University in London.

“But now we’re getting very, very high quality evidence from the epidemiological field, they’re showing in large populations of patients — as we’re seeing with the legalization of cannabis, more and more people are using it (because) of less restriction — and as a result of that we’re starting to see more adverse events such as heart disease and heart failure.”

The first study also found that people who reported daily marijuana use had a 34% increased risk of developing heart failure (a weakening of the heart to the point it can’t pump blood), compared to those who reported never using marijuana.

In a second U.S. study, researchers evaluated data from the 2019 National Inpatient Sample — the largest nationwide database of hospitalizations — to investigate whether hospital stays were complicated by a cardiovascular event, including heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest or arrhythmia, in patients who used marijuana.

Researchers used records of adults older than age 65 years with cardiovascular risk factors who reported no tobacco use, and divided them into marijuana users and non-marijuana users.

The study found of the 28,535 cannabis users with existing cardiovascular risk factors (high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes or high cholesterol), 20% had an increased chance of having a major heart or brain event while hospitalized, compared to the group who did not use cannabis.

George Smitherman, president and CEO of the Cannabis Council of Canada — representing more than 30 licensed producers and processors of cannabis products, said both studies were helpful.

“I thought it was very, very valuable data in so far is it re-enforces something that is sometimes, I believe, missed which is that no one should associate cannabis consumption, perhaps best in that combusted form, as being benign,” said Smitherman.

“And I think the studies in that context were important and beneficial. There’s a high proportion of cannabis consumers in the recreational marketplace that associate their consumption with wellness, and that’s excellent, but we need to be eyes wide open.”

The second study also found 13.9% of cannabis users with cardiovascular risk factors had a major adverse heart and brain event while hospitalized compared to non-cannabis users.

Additionally, the cannabis users in comparison to non-cannabis users had a higher rate of heart attacks (7.6% versus 6%, respectively) and were more likely to be transferred to other facilities (28.9% vs. 19%).

Smitherman said he hopes the U.S. studies will have an impact on Canadian health policy going forward, with regard to the five-year-old Cannabis Act.

“I’m just about to turn 60 and through legalization there’s been no public health messaging to me through the public health agency or anyone to say, ‘Hey, daily user of cannabis have you thought about maybe getting your THC other than through your lungs,’” he said. People can consume THC by such means as ingesting edibles, and oils.

Cannabis use may raise risk of heart failure, strokes and heart attacks: Studies

Regular cannabis use may raise the risk for heart failure, stroke or heart attack according to two preliminary studies.

One of world’s largest icebergs drifting beyond Antarctic waters after it was grounded for 3 decades

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Published Nov 26, 2023 • 1 minute read

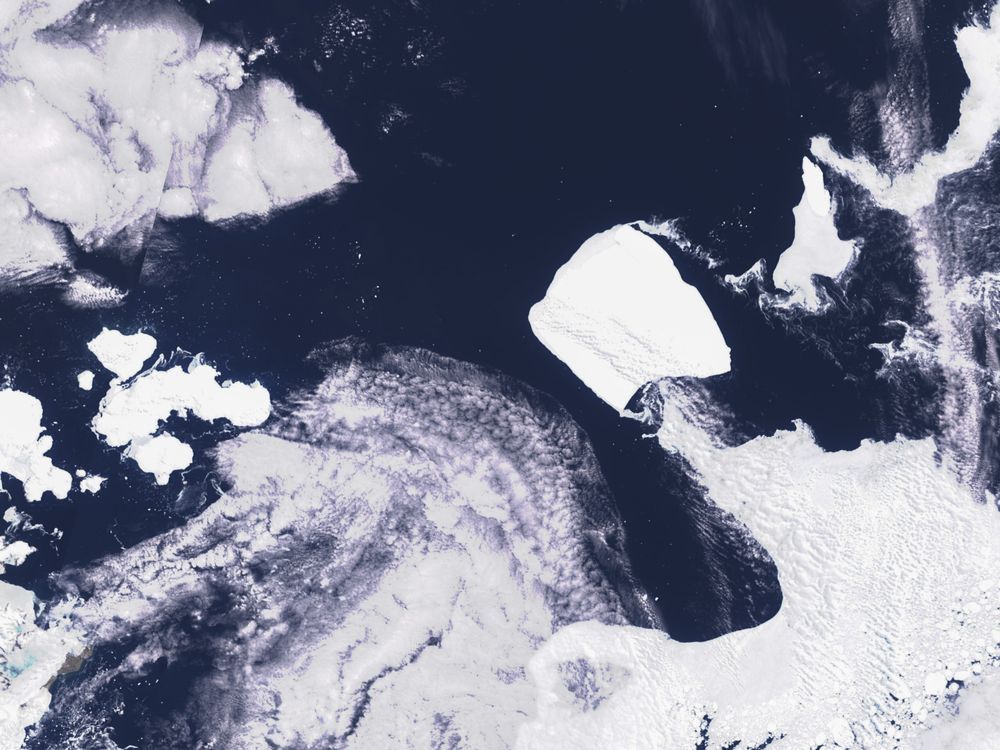

This images provided by Maxar Technologies shows the A23a iceberg moving through the sea sea near the Antarctica, on Wednesday Nov. 15, 2023. One of the world's largest icebergs, known as A23a, appears to be moving beyond Antarctic waters after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey. (Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies via AP)

This images provided by Maxar Technologies shows the A23a iceberg moving through the sea sea near the Antarctica, on Wednesday Nov. 15, 2023. One of the world's largest icebergs, known as A23a, appears to be moving beyond Antarctic waters after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey. (Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies via AP) THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

LONDON (AP) — One of the world’s largest icebergs is drifting beyond Antarctic waters, after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey.

The iceberg, known as A23a, split from the Antarctic’s Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986. But it became stuck to the ocean floor and had remained for many years in the Weddell Sea.

The iceberg is about three times the size of New York City and more than twice the size of Greater London, measuring around 4,000 square kilometers (1,500 square miles).

Andrew Fleming, a remote sensing expert from the British Antarctic Survey, told the BBC on Friday that the iceberg has been drifting for the past year and now appears to be picking up speed and moving past the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, helped by wind and ocean currents.

“I asked a couple of colleagues about this, wondering if there was any possible change in shelf water temperatures that might have provoked it, but the consensus is the time had just come,” Fleming told the BBC.

“It was grounded since 1986, but eventually it was going to decrease (in size) sufficiently was to lose grip and start moving,” he added.

Fleming said he first spotted movement from the iceberg in 2020. The British Antarctic Survey said it has now ungrounded and is moving along ocean currents to sub-Antarctic South Georgia.

![antarctica-iceberg[1].jpg antarctica-iceberg[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18422-d184f2adcf94960cfce298431b509f8f.jpg)

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Published Nov 26, 2023 • 1 minute read

This images provided by Maxar Technologies shows the A23a iceberg moving through the sea sea near the Antarctica, on Wednesday Nov. 15, 2023. One of the world's largest icebergs, known as A23a, appears to be moving beyond Antarctic waters after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey. (Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies via AP)

This images provided by Maxar Technologies shows the A23a iceberg moving through the sea sea near the Antarctica, on Wednesday Nov. 15, 2023. One of the world's largest icebergs, known as A23a, appears to be moving beyond Antarctic waters after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey. (Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies via AP) THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

LONDON (AP) — One of the world’s largest icebergs is drifting beyond Antarctic waters, after being grounded for more than three decades, according to the British Antarctic Survey.

The iceberg, known as A23a, split from the Antarctic’s Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986. But it became stuck to the ocean floor and had remained for many years in the Weddell Sea.

The iceberg is about three times the size of New York City and more than twice the size of Greater London, measuring around 4,000 square kilometers (1,500 square miles).

Andrew Fleming, a remote sensing expert from the British Antarctic Survey, told the BBC on Friday that the iceberg has been drifting for the past year and now appears to be picking up speed and moving past the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, helped by wind and ocean currents.

“I asked a couple of colleagues about this, wondering if there was any possible change in shelf water temperatures that might have provoked it, but the consensus is the time had just come,” Fleming told the BBC.

“It was grounded since 1986, but eventually it was going to decrease (in size) sufficiently was to lose grip and start moving,” he added.

Fleming said he first spotted movement from the iceberg in 2020. The British Antarctic Survey said it has now ungrounded and is moving along ocean currents to sub-Antarctic South Georgia.

![antarctica-iceberg[1].jpg antarctica-iceberg[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18422-d184f2adcf94960cfce298431b509f8f.jpg)

One of world’s largest icebergs drifting beyond Antarctic waters after it was grounded for 3 decades

Iceberg was previously grounded for three decades.

Shopper says he finds live worm in package of fish from Toronto grocery store

Author of the article enette Wilford

enette Wilford

Published Nov 28, 2023 • Last updated 18 hours ago • 1 minute read

Worm in package of fish purchased at Metro location in Toronto.

Worm in package of fish purchased at Metro location in Toronto. PHOTO BY SUPPLIED

A Toronto man says he was shocked to find what appeared to be a worm crawling in a package of fish he had just purchased from a local grocery store.

Yaroslav Kasyanenko had done a grocery run at a Metro location in Liberty Village on Nov. 27, got home and was about to cook when he saw the live worm next to what was going to be his dinner.

“We bought a Pacific snapper, it seemed fresh, and when we were about to start cooking at home, we found the worm,” Kasyanenko told The Toronto Sun.

“Half an hour later I was back in the store and I asked to speak to the manager,” he said.

Kasyanenko explained that he has worked 17 years in the heavily regulated hospitality industry and claimed the “response and attitude” he received from the manager he spoke to was “very unprofessional.”

“She never apologized and on top of everything, she told me, ‘This is normal for fish to have worms, you can Google it.’”

Kasyanenko said this wasn’t the first time he had an issue with seafood purchased at that particular Metro store.

“About three months ago, right after the strike ended, I bought lobster also packed in-store,” he said.

“The lobster was frozen however when I defrosted it, it turned dark brown and smelled bad,” Kasyanenko recalled.

“I took it to the store and asked for a reimbursement.”

Kasyanenko said a store manager tried to contact him Tuesday to say that “these things happen.”

Metro offered to give him a customer credit, but Kasyanenko refused, complaining the situation was “poorly handled.”

A representative from Metro told the Sun, “We are in touch with the customer to resolve this matter and we apologize for the inconvenience they experienced.”

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article

Published Nov 28, 2023 • Last updated 18 hours ago • 1 minute read

Worm in package of fish purchased at Metro location in Toronto.

Worm in package of fish purchased at Metro location in Toronto. PHOTO BY SUPPLIED

A Toronto man says he was shocked to find what appeared to be a worm crawling in a package of fish he had just purchased from a local grocery store.

Yaroslav Kasyanenko had done a grocery run at a Metro location in Liberty Village on Nov. 27, got home and was about to cook when he saw the live worm next to what was going to be his dinner.

“We bought a Pacific snapper, it seemed fresh, and when we were about to start cooking at home, we found the worm,” Kasyanenko told The Toronto Sun.

“Half an hour later I was back in the store and I asked to speak to the manager,” he said.

Kasyanenko explained that he has worked 17 years in the heavily regulated hospitality industry and claimed the “response and attitude” he received from the manager he spoke to was “very unprofessional.”

“She never apologized and on top of everything, she told me, ‘This is normal for fish to have worms, you can Google it.’”

Kasyanenko said this wasn’t the first time he had an issue with seafood purchased at that particular Metro store.

“About three months ago, right after the strike ended, I bought lobster also packed in-store,” he said.

“The lobster was frozen however when I defrosted it, it turned dark brown and smelled bad,” Kasyanenko recalled.

“I took it to the store and asked for a reimbursement.”

Kasyanenko said a store manager tried to contact him Tuesday to say that “these things happen.”

Metro offered to give him a customer credit, but Kasyanenko refused, complaining the situation was “poorly handled.”

A representative from Metro told the Sun, “We are in touch with the customer to resolve this matter and we apologize for the inconvenience they experienced.”

Shopper says he finds live worm in package of fish from Toronto grocery store

A Toronto man was horrified to find what appeared to be a little worm crawling in fish he had just purchased from a local grocery store.

oh ffs, such melodrama! would it have been better if the worm was dead?

here's what ya do... quit your whining, pick out the worm, rinse off your fish and cook and enjoy your fish. one worm will not affect the flavour of your fish to any great degree. yeah yeah it's the principle, I know. You're paying 50bux/lb for fresh fish and you don't want a fvcking worm in it. hey here's a thought, for that price how about you look at what you're buying before you buy it? that worm could have been easily noticed... anything smaller? well, isn't that why we cook food in the first place? to kill anything microscopic we can't visually detect? otherwise.... more protein!

and that's nothing compared to what bugs the gates/schwab/soros compact will have you eating if we don't rise up en masse with pitchforks not made in china and put an end to their utopian nightmare.

dammit we need a war just so crybabies can know there really are things to cry about.

here's what ya do... quit your whining, pick out the worm, rinse off your fish and cook and enjoy your fish. one worm will not affect the flavour of your fish to any great degree. yeah yeah it's the principle, I know. You're paying 50bux/lb for fresh fish and you don't want a fvcking worm in it. hey here's a thought, for that price how about you look at what you're buying before you buy it? that worm could have been easily noticed... anything smaller? well, isn't that why we cook food in the first place? to kill anything microscopic we can't visually detect? otherwise.... more protein!

and that's nothing compared to what bugs the gates/schwab/soros compact will have you eating if we don't rise up en masse with pitchforks not made in china and put an end to their utopian nightmare.

dammit we need a war just so crybabies can know there really are things to cry about.

Diner claims she found part of manager's digit in salad

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Emily Heil, The Washington Post

Published Nov 29, 2023 • 2 minute read

A woman filed a lawsuit in Connecticut claiming she found part of a finger in her Chopt salad.

A woman filed a lawsuit in Connecticut claiming she found part of a finger in her Chopt salad. PHOTO BY CHOPT CREATIVE SALAD CO. /Instagram

A Connecticut woman is suing the fast-casual chain Chopt Creative Salad Company after being served a salad she says contained part of the severed finger of a manager, an account bolstered by a county health department’s inspection report.

According to the lawsuit, which was filed on Monday, Greenwich resident Allison Cozzi was eating a salad on April 7 when she “realized she was chewing on a portion of a human finger” that had been mixed into the dish. The digit, a part of a left index finger, belonged to a manager who had injured herself earlier in the day, the filing alleges.

The manager had been chopping arugula when she accidentally cut off part of her finger and went to the hospital for treatment, the lawsuit claims. Afterward, it alleges, the greens were not removed from the restaurant’s line, but remained and were served to customers, including Cozzi.

Chopt did not respond to an email seeking comment.

Details about the incident are also described in documents from the Westchester County Health Department, which inspected the Chopt location in Mount Kisco, N.Y., that Cozzi had visited.

According to an inspection report from the county, a manager identified as Keny M. told the inspector that she cut off the tip of her left forefinger while preparing arugula. After she left to seek medical treatment, “workers did not realize the arugula was contaminated with human blood and a finger tip skin” and was served to customers, according to the report.

A customer’s complaint about finding the finger was reported “to the store and to corporate,” but not to health officials, it states.

The report, which named Cozzi as the customer, said the “corrective action” included discussion of the requirement to notify the department of potential contamination and any potential illnesses caused by food served.

A hearing was held on the matter on May 25, according to the health department documents, during which a Chopt district manager said the “violations were corrected” and expressed “contrition for failure to report.” Chopt was fined a total of $900, records show.

Cozzi accused the restaurant of negligence and is seeking unspecified damages, claiming that she suffered from various injuries including shock, anxiety, panic attacks, nausea, vomiting and dizziness following the incident.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Emily Heil, The Washington Post

Published Nov 29, 2023 • 2 minute read

A woman filed a lawsuit in Connecticut claiming she found part of a finger in her Chopt salad.

A woman filed a lawsuit in Connecticut claiming she found part of a finger in her Chopt salad. PHOTO BY CHOPT CREATIVE SALAD CO. /Instagram

A Connecticut woman is suing the fast-casual chain Chopt Creative Salad Company after being served a salad she says contained part of the severed finger of a manager, an account bolstered by a county health department’s inspection report.

According to the lawsuit, which was filed on Monday, Greenwich resident Allison Cozzi was eating a salad on April 7 when she “realized she was chewing on a portion of a human finger” that had been mixed into the dish. The digit, a part of a left index finger, belonged to a manager who had injured herself earlier in the day, the filing alleges.

The manager had been chopping arugula when she accidentally cut off part of her finger and went to the hospital for treatment, the lawsuit claims. Afterward, it alleges, the greens were not removed from the restaurant’s line, but remained and were served to customers, including Cozzi.

Chopt did not respond to an email seeking comment.

Details about the incident are also described in documents from the Westchester County Health Department, which inspected the Chopt location in Mount Kisco, N.Y., that Cozzi had visited.

According to an inspection report from the county, a manager identified as Keny M. told the inspector that she cut off the tip of her left forefinger while preparing arugula. After she left to seek medical treatment, “workers did not realize the arugula was contaminated with human blood and a finger tip skin” and was served to customers, according to the report.

A customer’s complaint about finding the finger was reported “to the store and to corporate,” but not to health officials, it states.

The report, which named Cozzi as the customer, said the “corrective action” included discussion of the requirement to notify the department of potential contamination and any potential illnesses caused by food served.

A hearing was held on the matter on May 25, according to the health department documents, during which a Chopt district manager said the “violations were corrected” and expressed “contrition for failure to report.” Chopt was fined a total of $900, records show.

Cozzi accused the restaurant of negligence and is seeking unspecified damages, claiming that she suffered from various injuries including shock, anxiety, panic attacks, nausea, vomiting and dizziness following the incident.

CHOPT FINGER: Diner claims she found part of manager's digit in salad

A woman is suing the fast-casual chain Chopt Creative Salad Company after being served a salad she says contained part of a severed finger.

El Nino brings a warm start to winter, but that could change: Weather Network

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Rosa Saba

Published Nov 29, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 3 minute read

Chilly nights and snow-covered slopes may not be easy to come by in much of Canada during the first part of the winter season, according to the winter outlook from one of Canada’s prominent forecasters.

The Weather Network predicts El Nino conditions will lead to above-average temperatures and lower-than-normal precipitation levels in much of the country, particularly in Western and Central Canada.

While that trend is expected to hold throughout the winter in British Columbia and the Prairie provinces, the network said areas further east may see more variable conditions as the season progresses.

“It’s an El Nino unlike anything we’ve quite seen before. And that means there could be a few surprises in store this year for Canadians,” said Chris Scott, chief meteorologist at The Weather Network.

“Yes, El Nino means mild, but we’re going to have to watch for a change midwinter that could lead us down a different road than we’ve been down before.”

The forecaster said El Nino is associated with warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures in the tropical region of the Pacific Ocean to the west of South America, which affects the global jet stream pattern.

British Columbia is expected to have a milder and drier than normal winter for much of the season, The Weather Network said in a press release, though there could be a few periods of excessive rainfall.

The Prairie provinces, especially Alberta and Saskatchewan, should also expect a milder winter, with below-normal snowfall across western and central parts of the region. Scott noted that Edmonton has so far seen no snow in November — something that last happened almost 100 years ago.

For Western Canada, “this is the winter that you’d worry more than normal about having a brown Christmas,” he said.

But more traditional winter conditions could return to the Prairies for January and February, Scott said, especially in Manitoba.

The network anticipates a similar story to play out in Ontario and Quebec, where residents are slated to enjoy warmer temperatures and less snow than normal before things could take a turn for the colder.

El Nino tends to have its biggest influence on Western Canada because it’s a Pacific Ocean phenomenon, Scott explained. By the time the jet stream makes its way to southern Ontario and Quebec, it either continues east or travels south instead.

“While yes, part of this winter looks quite mild, we’re very interested in what happens in the midwinter period because this forecast really takes a fork in the road,” said Scott. “It either goes pretty mild for Ontario and Quebec, or it actually goes cold and we get some real winter to come.”

The result, Scott predicted, is that temperatures in cities like Toronto and Montreal will likely average out to be near seasonal norms.

The forecast for Atlantic Canada, meanwhile, suggests the region is in for a near-normal winter with periods of mild weather offset by colder stretches. Precipitation, too, will be near normal, expect for the southern Maritimes and the southeastern tip of Newfoundland, which could see above-normal levels.

“Even though this is an El Nino like we’ve never seen before, it doesn’t mean that we’re suddenly going to go mild in Atlantic Canada,” said Scott.

The network predicts Northern Canada should see a slightly milder winter this year, though colder weather may come to Yukon at the beginning of the season and northern Hudson Bay and Baffin Island could see a period of colder-than-normal temperatures deeper into the winter.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Rosa Saba

Published Nov 29, 2023 • Last updated 1 day ago • 3 minute read

Chilly nights and snow-covered slopes may not be easy to come by in much of Canada during the first part of the winter season, according to the winter outlook from one of Canada’s prominent forecasters.

The Weather Network predicts El Nino conditions will lead to above-average temperatures and lower-than-normal precipitation levels in much of the country, particularly in Western and Central Canada.

While that trend is expected to hold throughout the winter in British Columbia and the Prairie provinces, the network said areas further east may see more variable conditions as the season progresses.

“It’s an El Nino unlike anything we’ve quite seen before. And that means there could be a few surprises in store this year for Canadians,” said Chris Scott, chief meteorologist at The Weather Network.

“Yes, El Nino means mild, but we’re going to have to watch for a change midwinter that could lead us down a different road than we’ve been down before.”

The forecaster said El Nino is associated with warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures in the tropical region of the Pacific Ocean to the west of South America, which affects the global jet stream pattern.

British Columbia is expected to have a milder and drier than normal winter for much of the season, The Weather Network said in a press release, though there could be a few periods of excessive rainfall.

The Prairie provinces, especially Alberta and Saskatchewan, should also expect a milder winter, with below-normal snowfall across western and central parts of the region. Scott noted that Edmonton has so far seen no snow in November — something that last happened almost 100 years ago.

For Western Canada, “this is the winter that you’d worry more than normal about having a brown Christmas,” he said.

But more traditional winter conditions could return to the Prairies for January and February, Scott said, especially in Manitoba.

The network anticipates a similar story to play out in Ontario and Quebec, where residents are slated to enjoy warmer temperatures and less snow than normal before things could take a turn for the colder.

El Nino tends to have its biggest influence on Western Canada because it’s a Pacific Ocean phenomenon, Scott explained. By the time the jet stream makes its way to southern Ontario and Quebec, it either continues east or travels south instead.

“While yes, part of this winter looks quite mild, we’re very interested in what happens in the midwinter period because this forecast really takes a fork in the road,” said Scott. “It either goes pretty mild for Ontario and Quebec, or it actually goes cold and we get some real winter to come.”

The result, Scott predicted, is that temperatures in cities like Toronto and Montreal will likely average out to be near seasonal norms.

The forecast for Atlantic Canada, meanwhile, suggests the region is in for a near-normal winter with periods of mild weather offset by colder stretches. Precipitation, too, will be near normal, expect for the southern Maritimes and the southeastern tip of Newfoundland, which could see above-normal levels.

“Even though this is an El Nino like we’ve never seen before, it doesn’t mean that we’re suddenly going to go mild in Atlantic Canada,” said Scott.

The network predicts Northern Canada should see a slightly milder winter this year, though colder weather may come to Yukon at the beginning of the season and northern Hudson Bay and Baffin Island could see a period of colder-than-normal temperatures deeper into the winter.

El Nino brings a warm start to winter, but that could change: Weather Network

Chilly nights and snow-covered slopes may not be easy to come by in much of Canada during the first part of the winter season.

Golden mole not seen for 80 years and presumed extinct is found again in South Africa

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Gerald Imray

Published Nov 30, 2023 • 2 minute read

This photo provided by RE:wild shows a rediscovered mole on the west coast of South Africa. Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a mole species that has an iridescent golden coat and "swims" through sand dunes after it hadn't been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct.

This photo provided by RE:wild shows a rediscovered mole on the west coast of South Africa. Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a mole species that has an iridescent golden coat and "swims" through sand dunes after it hadn't been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct. PHOTO BY NICKY SOUNESS /THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) — Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a species of mole with an iridescent golden coat and the ability to almost “swim” through sand dunes after it hadn’t been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct.

The De Winton’s golden mole — a small, blind burrower with “super-hearing powers” that eats insects — was found to be still alive on a beach in Port Nolloth on the west coast of South Africa by a team of researchers from the Endangered Wildlife Trust and the University of Pretoria.

It had been lost to science since 1936, the researchers said.

With the help of a sniffer dog, the team found traces of tunnels and discovered a golden mole in 2021. But because there are 21 species of golden moles and some look very similar, the team needed more to be certain that it was a De Winton’s.

They took environmental DNA samples — the DNA animals leave behind in skin cells, hair and bodily excretions — but had to wait until 2022 before a De Winton’s DNA sample from decades ago was made available by a South African museum to compare. The DNA sequences were a match.

The team’s research and findings were peer reviewed and published last week.

“We had high hopes, but we also had our hopes crushed by a few people,” one of the researchers, Samantha Mynhardt, told The Associated Press. “One De Winton’s expert told us, ‘you’re not going to find that mole. It’s extinct.”‘

The process took three years from the researchers’ first trip to the west coast of South Africa to start searching for the mole, which was known to rarely leave signs of its tunnels and almost “swim” under the sand dunes, the researchers said. Golden moles are native to sub-Saharan Africa and the De Winton’s had only ever been found in the Port Nolloth area.

Two De Winton’s golden moles have now been confirmed and photographed in Port Nolloth, Mynhardt said, while the research team has found signs of other populations in the area since 2021.

“It was a very exciting project with many challenges,” said Esther Matthew, senior field officer with the Endangered Wildlife Trust. “Luckily we had a fantastic team full of enthusiasm and innovative ideas, which is exactly what you need when you have to survey up to 18 kilometers (11 miles) of dune habitat in a day.”

The De Winton’s golden mole was on a “most wanted lost species” list compiled by the Re:wild conservation group.

Others on the list that have been rediscovered include a salamander that was found in Guatemala in 2017, 42 years after its last sighting, and an elephant shrew called the Somali sengi seen in Djibouti in 2019, its first recorded sighting since 1968.

![south-africa-rediscovered-mole[1].jpg south-africa-rediscovered-mole[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18477-c4ee08228adb911df45443bd0c7d7158.jpg)

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Gerald Imray

Published Nov 30, 2023 • 2 minute read

This photo provided by RE:wild shows a rediscovered mole on the west coast of South Africa. Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a mole species that has an iridescent golden coat and "swims" through sand dunes after it hadn't been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct.

This photo provided by RE:wild shows a rediscovered mole on the west coast of South Africa. Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a mole species that has an iridescent golden coat and "swims" through sand dunes after it hadn't been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct. PHOTO BY NICKY SOUNESS /THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) — Researchers in South Africa say they have rediscovered a species of mole with an iridescent golden coat and the ability to almost “swim” through sand dunes after it hadn’t been seen for more than 80 years and was thought to be extinct.

The De Winton’s golden mole — a small, blind burrower with “super-hearing powers” that eats insects — was found to be still alive on a beach in Port Nolloth on the west coast of South Africa by a team of researchers from the Endangered Wildlife Trust and the University of Pretoria.

It had been lost to science since 1936, the researchers said.

With the help of a sniffer dog, the team found traces of tunnels and discovered a golden mole in 2021. But because there are 21 species of golden moles and some look very similar, the team needed more to be certain that it was a De Winton’s.

They took environmental DNA samples — the DNA animals leave behind in skin cells, hair and bodily excretions — but had to wait until 2022 before a De Winton’s DNA sample from decades ago was made available by a South African museum to compare. The DNA sequences were a match.

The team’s research and findings were peer reviewed and published last week.

“We had high hopes, but we also had our hopes crushed by a few people,” one of the researchers, Samantha Mynhardt, told The Associated Press. “One De Winton’s expert told us, ‘you’re not going to find that mole. It’s extinct.”‘

The process took three years from the researchers’ first trip to the west coast of South Africa to start searching for the mole, which was known to rarely leave signs of its tunnels and almost “swim” under the sand dunes, the researchers said. Golden moles are native to sub-Saharan Africa and the De Winton’s had only ever been found in the Port Nolloth area.

Two De Winton’s golden moles have now been confirmed and photographed in Port Nolloth, Mynhardt said, while the research team has found signs of other populations in the area since 2021.

“It was a very exciting project with many challenges,” said Esther Matthew, senior field officer with the Endangered Wildlife Trust. “Luckily we had a fantastic team full of enthusiasm and innovative ideas, which is exactly what you need when you have to survey up to 18 kilometers (11 miles) of dune habitat in a day.”

The De Winton’s golden mole was on a “most wanted lost species” list compiled by the Re:wild conservation group.

Others on the list that have been rediscovered include a salamander that was found in Guatemala in 2017, 42 years after its last sighting, and an elephant shrew called the Somali sengi seen in Djibouti in 2019, its first recorded sighting since 1968.

![south-africa-rediscovered-mole[1].jpg south-africa-rediscovered-mole[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18477-c4ee08228adb911df45443bd0c7d7158.jpg)

STILL ALIVE!: Golden mole not seen for 80 years and presumed extinct is found again in South Africa

It had been lost to science since 1936, the researchers said.

Long-haired rodents invade Australian coastal towns

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Jonathan Edwards, The Washington Post

Published Nov 30, 2023 • Last updated 2 days ago • 4 minute read

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows a native long-haired rat on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows a native long-haired rat on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland. PHOTO BY JANINE HARRIS / THIS IS LIVIN / AFP /Getty Images

Emma Gray was among the first to notice signs of the impending plague.

A biological researcher, Gray went to northwest Queensland in Australia in June to study one mammal but unexpectedly ended up focusing on another. During her field work, she caught more than 1,000 long-haired rats. As Gray looked around, she saw evidence of far more.

“You could just see tunnels everywhere in the grass,” Gray, a postdoctoral researcher at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, told The Washington Post.

Gray said she immediately knew what was happening: an explosion in the number of long-haired rats. Native to Australia, long-haired rats normally eke out an existence in relatively low numbers, only to skyrocket into legions when the right conditions present themselves.

Gray was right. Hordes of the rats have since spread north as government officials warn of a “Rat Plague.” The rats have most recently hit the country’s coastal towns, including Karumba, where they have chewed through electrical wires, devoured food reserves, attacked pets and, in at least one case, destroyed a car.

“They’re causing havoc with everything,” a Karumba resident told 4BC radio, adding: “They’re eating anything and everything they can get their hands on.”

Known as Rattus villosissimus to scientists and majaru or mayaroo to Indigenous Australians, the long-haired rat typically lives in arid and semiarid habitats. They normally hide inside cracks in clay soil, which provide shelter both from the heat and from predators such as barn owls, letter-winged kites and feral cats, Gray said.

Long-haired rats eat wild plants, specifically their leaves and seeds, Gray added, because unlike the brown rats familiar to city dwellers around the world, they are not commensal, or reliant on humans for food and shelter. Every three to five years, though sometimes more often, La Nina weather brings increased rainfall to Australia, including every year since 2020, when an unusual “triple-dip” La Niña unleashed record-breaking rains across the country, causing flooding and forcing evacuations, the BBC reported.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows native long-haired rats on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris’s facebook page ‘This Is Livin’ shows native long-haired rats on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia’s Queensland. PHOTO BY JANINE HARRIS / THIS IS LIVIN / AFP /Getty Images

For the long-haired rat, more rain means more vegetation growth, and more food means more rats – lots more. With a strong food supply, long-haired rats can give birth every three weeks, producing litters with as many as 12 babies, Gray said.

“It’s a very natural phenomenon that’s been happening basically as far back as our records go, to early explorers,” she said, adding that, despite the lack of historical records, she suspects the boom-and-bust cycle has been going on for thousands, if not tens of thousands, of years.

Explosions in the long-haired rat population happen every three to 17 years, the last one occurring in 2011 after two years of above-average rainfall, Gray said. Luke Wharton, a resident of a nearby community that was also hit by rats, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation that this year’s plague “might top it.”

More rats mean more problems, at least for people.

“They’re quite destructive when they get into such large numbers,” Gray said.

Karumba is only the latest town to suffer under the onslaught. After Gray’s discovery in June near the inland town of Julia Creek, the rats marched steadily northward, hitting other inland communities as they pressed toward the sea, according to the ABC. Along the way, they contaminated water sources and destroyed crops.

Long-haired rats have quickly worn out their welcome in Karumba. Jemma Probert, who owns a fishing charter, told the ABC that she’s had to flick them off her boat, while commercial fisherman Brett Fallon told the news organization that every night, at least 100 invade his vessel. Derek Lord, who runs a car rental business, told the AFP that they destroyed a vehicle by stripping the wiring out of the engine bay. He said they also drove his pet ducks “mad” by breaking into their cages and stealing their eggs.

“There’s rats everywhere,” Lord said, adding: “They’re just like, bold as hell.”

The rats swim out to sandbanks during low tide, only to drown when the water rises, Probert told the ABC. Fallon said that he caught sight of their corpses floating on the water surface.

“When the moon came over the town last night, the river was well and truly alive with the bodies of rats,” he said.

The rats’ bodies – thousands and thousands of them – then wash ashore. While government officials clean up many of them, others rot.

“The stench is quite bad,” Carpentaria Shire Council Mayor Jack Bawden, who represents Karumba, told NPR.

But spikes in the long-haired rat population end quickly. Although scientists aren’t exactly sure why, a number of factors are thought to contribute, including inbreeding, an increase in the number of predators and a declining food supply.

Although the triple-dip La Nina ended earlier this year, Australia is moving into the wet season, when the rats’ food supply should be ample, University of Sydney environmental sciences professor Peter Banks told the ABC. Bawden told the news agency that he and other local government officials are preparing to cope with wave after wave of tiny, four-legged invaders.

“We’re not getting any relief anytime soon,” he said, adding: “We may just have to wait it out.”

![Australia-rats1-Nov30-e1701356747624[1].jpg Australia-rats1-Nov30-e1701356747624[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18482-fdd22407edaa4b32417790be0f0c7820.jpg)

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Jonathan Edwards, The Washington Post

Published Nov 30, 2023 • Last updated 2 days ago • 4 minute read

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows a native long-haired rat on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows a native long-haired rat on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland. PHOTO BY JANINE HARRIS / THIS IS LIVIN / AFP /Getty Images

Emma Gray was among the first to notice signs of the impending plague.

A biological researcher, Gray went to northwest Queensland in Australia in June to study one mammal but unexpectedly ended up focusing on another. During her field work, she caught more than 1,000 long-haired rats. As Gray looked around, she saw evidence of far more.

“You could just see tunnels everywhere in the grass,” Gray, a postdoctoral researcher at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, told The Washington Post.

Gray said she immediately knew what was happening: an explosion in the number of long-haired rats. Native to Australia, long-haired rats normally eke out an existence in relatively low numbers, only to skyrocket into legions when the right conditions present themselves.

Gray was right. Hordes of the rats have since spread north as government officials warn of a “Rat Plague.” The rats have most recently hit the country’s coastal towns, including Karumba, where they have chewed through electrical wires, devoured food reserves, attacked pets and, in at least one case, destroyed a car.

“They’re causing havoc with everything,” a Karumba resident told 4BC radio, adding: “They’re eating anything and everything they can get their hands on.”

Known as Rattus villosissimus to scientists and majaru or mayaroo to Indigenous Australians, the long-haired rat typically lives in arid and semiarid habitats. They normally hide inside cracks in clay soil, which provide shelter both from the heat and from predators such as barn owls, letter-winged kites and feral cats, Gray said.

Long-haired rats eat wild plants, specifically their leaves and seeds, Gray added, because unlike the brown rats familiar to city dwellers around the world, they are not commensal, or reliant on humans for food and shelter. Every three to five years, though sometimes more often, La Nina weather brings increased rainfall to Australia, including every year since 2020, when an unusual “triple-dip” La Niña unleashed record-breaking rains across the country, causing flooding and forcing evacuations, the BBC reported.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris's facebook page 'This Is Livin' shows native long-haired rats on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia's Queensland.

This handout photo taken Nov. 13, 2023, and obtained on Nov. 24, 2023 from Janine Harris’s facebook page ‘This Is Livin’ shows native long-haired rats on a beach in the town of Karumba, in Australia’s Queensland. PHOTO BY JANINE HARRIS / THIS IS LIVIN / AFP /Getty Images

For the long-haired rat, more rain means more vegetation growth, and more food means more rats – lots more. With a strong food supply, long-haired rats can give birth every three weeks, producing litters with as many as 12 babies, Gray said.

“It’s a very natural phenomenon that’s been happening basically as far back as our records go, to early explorers,” she said, adding that, despite the lack of historical records, she suspects the boom-and-bust cycle has been going on for thousands, if not tens of thousands, of years.

Explosions in the long-haired rat population happen every three to 17 years, the last one occurring in 2011 after two years of above-average rainfall, Gray said. Luke Wharton, a resident of a nearby community that was also hit by rats, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation that this year’s plague “might top it.”

More rats mean more problems, at least for people.

“They’re quite destructive when they get into such large numbers,” Gray said.

Karumba is only the latest town to suffer under the onslaught. After Gray’s discovery in June near the inland town of Julia Creek, the rats marched steadily northward, hitting other inland communities as they pressed toward the sea, according to the ABC. Along the way, they contaminated water sources and destroyed crops.

Long-haired rats have quickly worn out their welcome in Karumba. Jemma Probert, who owns a fishing charter, told the ABC that she’s had to flick them off her boat, while commercial fisherman Brett Fallon told the news organization that every night, at least 100 invade his vessel. Derek Lord, who runs a car rental business, told the AFP that they destroyed a vehicle by stripping the wiring out of the engine bay. He said they also drove his pet ducks “mad” by breaking into their cages and stealing their eggs.

“There’s rats everywhere,” Lord said, adding: “They’re just like, bold as hell.”

The rats swim out to sandbanks during low tide, only to drown when the water rises, Probert told the ABC. Fallon said that he caught sight of their corpses floating on the water surface.

“When the moon came over the town last night, the river was well and truly alive with the bodies of rats,” he said.

The rats’ bodies – thousands and thousands of them – then wash ashore. While government officials clean up many of them, others rot.

“The stench is quite bad,” Carpentaria Shire Council Mayor Jack Bawden, who represents Karumba, told NPR.

But spikes in the long-haired rat population end quickly. Although scientists aren’t exactly sure why, a number of factors are thought to contribute, including inbreeding, an increase in the number of predators and a declining food supply.

Although the triple-dip La Nina ended earlier this year, Australia is moving into the wet season, when the rats’ food supply should be ample, University of Sydney environmental sciences professor Peter Banks told the ABC. Bawden told the news agency that he and other local government officials are preparing to cope with wave after wave of tiny, four-legged invaders.

“We’re not getting any relief anytime soon,” he said, adding: “We may just have to wait it out.”

![Australia-rats1-Nov30-e1701356747624[1].jpg Australia-rats1-Nov30-e1701356747624[1].jpg](https://forums.canadiancontent.net/data/attachments/18/18482-fdd22407edaa4b32417790be0f0c7820.jpg)

'RAT PLAGUE': Long-haired rodents invade Australian coastal towns

Emma Gray was among the first to notice signs of the impending plague.

Attachments

is that how long it's been stuck in Richard Gere's rectum (damn-near-killed-'im)?

:?P

those rats look like they tied into a mousse!

'RAT PLAGUE': Long-haired rodents invade Australian coastal towns

Emma Gray was among the first to notice signs of the impending plague.torontosun.com

Billionaire Texan heir helping bring back woolly mammoth

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Shelly Hagan

Published Dec 01, 2023 • 5 minute read

A Texas oil heir’s quest to make Dallas a hub for biotech is showing signs of paying off, potentially paving the way for scientific discoveries ranging from reviving the woolly mammoth to treatments for cancer.

Lyda Hill, the 81-year-old granddaughter of wildcatter H.L. Hunt, has funneled millions of philanthropic and investment dollars into developing the industry in her hometown. In September, her marquee project, an office campus modelled after the Kendall Square innovation district near MIT, scored a big win when it was named one of the three headquarters for the federal government’s new health research institutes.

Hill is extending a family tradition in helping shape Dallas. Her grandfather and assorted relatives were instrumental in turning the city into a centre for oil and gas, and she’s now seeking to usher in what she hopes is its next era.

Her biotech push is coming up against the city’s geographic sprawl and a relative lack of capital compared with hubs like Boston or San Francisco. But it echoes efforts by cities including Chicago and Salt Lake City, which are trying to cash in on a windfall of public and private funding for biomedical manufacturing and research in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Winning the research institute caps a successful start for Hill’s 30-month-old campus, known as Pegasus Park. It beat out Massachusetts to lure the headquarters for a $1 billion “de-extinction” startup called Colossal Biosciences that is seeking to revive the woolly mammoth along with the Tasmanian tiger and other long-gone species. Just this week, the company announced an agreement with the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation to host dodo birds if it’s successful in reviving them.

BioLabs, a co-working company focused on the life sciences industry, has its only US location outside the coastal states at Pegasus Park. And now it will have the new federal research hub that will focus on project management for biotech studies and trials.

Hill, who declined a request for an interview, is from one of the most prominent Dallas dynasties, though she zealously guards her privacy. Her grandfather, an avid gambler who grew up on an Illinois farm, turned a $50 loan into what eventually became one of the largest US oil companies, with Life Magazine calling him the richest man in the U.S. in 1948.

He had 15 children, including Hill’s mother Margaret Hunt Hill, who has an iconic bridge named after her over the Trinity River in Dallas. Lamar Hunt founded the American Football League and created the Super Bowl.

Many of the descendants of H.L. Hunt have gone on to be influential figures, mostly in Dallas but also Kansas City and Chicago. They’ve built skyscrapers and bought sports teams, and used their fortunes to give back. Clark Hunt, chief executive of the Kansas City Chiefs, leads the Hunt Family Foundation that focuses on providing basic necessities for those in need. Luxury hotel magnate Caroline Rose Hunt, who died in 2018, joined with her grandchildren to donate $5 million to United Way of Metropolitan Dallas in 2015.

“There’s a reputation for wealth building, but there’s also a reputation for setting that aside in favour of community building and doing something that’s gonna benefit the city long term,” said Cal Jillson, a professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Hill has done just that in the life sciences industry, partly motivated by her own battle with breast cancer. Her charitable donations include $50 million to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Moon Shots Program; $50 million to the UT Southwestern Medical Center that was partly used to create the Lyda Hill Department of Bioinformatics; $20 million to the Hockaday School, a private all girls school in Dallas, to fund science-focused programs; and $30 million to the Dallas-based Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.

On the investment side, she provided early funding to Peloton Therapeutics, which was acquired by Merck & Co. in 2019.

For now, most of her attention is going to Pegasus Park, which seeks to overcome one of Dallas’s most vexing challenges to becoming a biotech hub. Cities like Boston, San Francisco and New York enjoy a concentration of capital, entrepreneurs and academia in a small area. Dallas struggles with dispersion — while the city’s population is 1.3 million, the sprawling Dallas-Fort Worth metro area boasts some 8 million residents.

“Metros that are the size of DFW historically have challenges finding a way to keep these companies clustered together in the same neighbourhood,” said Travis McCready, the head of the life sciences practice in the Americas at JLL, a $7 billion global real estate company.

The 26-acre campus sits near the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, a research institute that employs six Nobel laureates. Several of the professors work on startups that operate out of BioLabs. And the campus is expanding — construction has started on a new wing that will be a laboratory facility.

Steve Case, the billionaire co-founder of AOL, said during a visit to Pegasus Park in September that such hubs can fuel innovation just by bringing together people from different companies and institutions who wouldn’t normally collaborate.

“The very beginning of what’s happening here is quite encouraging and I think bodes well for this next chapter,” said Case, who now runs investment firm Revolution, which focuses on investments in places outside of traditional venture hubs like San Francisco and Boston.

What Dallas lacks, and what Case’s firm is trying to solve, is access to capital. Venture capital funding in Dallas was $157 million in the third quarter, versus $10.2 billion in San Francisco and $3.5 billion in Boston, according to PitchBook data.

BioLabs has been hosting informal meetings at Old Parkland, an office park in Dallas that houses asset management firms, to tout investment opportunities at Pegasus Park. Gabby Everett, a scientist and director of the Dallas Biolabs site, said there are ongoing discussions between some founders and investors.

Hill’s representatives say her involvement in Pegasus Park includes a mix of philanthropic efforts and for-profit investments, but declined to provide a detailed breakdown.

Another developer is looking to cash in on the biotech industry in North Texas. NexPoint founder James Dondero has proposed a $4 billion project that would convert Ross Perot’s former Electronic Data Systems campus in the Dallas suburb of Plano into a life sciences hub. NexPoint received rezoning approval from the Plano city council in November.

The region is already home to major life science firms including Irving-based McKesson Corp. and Galderma, which has its U.S. headquarters in Fort Worth. The DFW airport was one of the first in the country to support cold chain cargo for pharmaceutical shipments.

Texas economist Ray Perryman said North Texas has all the ingredients for a thriving life sciences community including a large and expanding population, skilled workforce, quality health care systems, research and education centres and a vibrant financial sector.

“Dallas-Fort Worth has tremendous potential to be a biotech, life sciences hub of global significance,” he said. “The industry has been growing very rapidly and it’s viewed favourably by the investment community.”

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Shelly Hagan

Published Dec 01, 2023 • 5 minute read

A Texas oil heir’s quest to make Dallas a hub for biotech is showing signs of paying off, potentially paving the way for scientific discoveries ranging from reviving the woolly mammoth to treatments for cancer.

Lyda Hill, the 81-year-old granddaughter of wildcatter H.L. Hunt, has funneled millions of philanthropic and investment dollars into developing the industry in her hometown. In September, her marquee project, an office campus modelled after the Kendall Square innovation district near MIT, scored a big win when it was named one of the three headquarters for the federal government’s new health research institutes.

Hill is extending a family tradition in helping shape Dallas. Her grandfather and assorted relatives were instrumental in turning the city into a centre for oil and gas, and she’s now seeking to usher in what she hopes is its next era.

Her biotech push is coming up against the city’s geographic sprawl and a relative lack of capital compared with hubs like Boston or San Francisco. But it echoes efforts by cities including Chicago and Salt Lake City, which are trying to cash in on a windfall of public and private funding for biomedical manufacturing and research in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Winning the research institute caps a successful start for Hill’s 30-month-old campus, known as Pegasus Park. It beat out Massachusetts to lure the headquarters for a $1 billion “de-extinction” startup called Colossal Biosciences that is seeking to revive the woolly mammoth along with the Tasmanian tiger and other long-gone species. Just this week, the company announced an agreement with the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation to host dodo birds if it’s successful in reviving them.

BioLabs, a co-working company focused on the life sciences industry, has its only US location outside the coastal states at Pegasus Park. And now it will have the new federal research hub that will focus on project management for biotech studies and trials.

Hill, who declined a request for an interview, is from one of the most prominent Dallas dynasties, though she zealously guards her privacy. Her grandfather, an avid gambler who grew up on an Illinois farm, turned a $50 loan into what eventually became one of the largest US oil companies, with Life Magazine calling him the richest man in the U.S. in 1948.

He had 15 children, including Hill’s mother Margaret Hunt Hill, who has an iconic bridge named after her over the Trinity River in Dallas. Lamar Hunt founded the American Football League and created the Super Bowl.

Many of the descendants of H.L. Hunt have gone on to be influential figures, mostly in Dallas but also Kansas City and Chicago. They’ve built skyscrapers and bought sports teams, and used their fortunes to give back. Clark Hunt, chief executive of the Kansas City Chiefs, leads the Hunt Family Foundation that focuses on providing basic necessities for those in need. Luxury hotel magnate Caroline Rose Hunt, who died in 2018, joined with her grandchildren to donate $5 million to United Way of Metropolitan Dallas in 2015.

“There’s a reputation for wealth building, but there’s also a reputation for setting that aside in favour of community building and doing something that’s gonna benefit the city long term,” said Cal Jillson, a professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Hill has done just that in the life sciences industry, partly motivated by her own battle with breast cancer. Her charitable donations include $50 million to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Moon Shots Program; $50 million to the UT Southwestern Medical Center that was partly used to create the Lyda Hill Department of Bioinformatics; $20 million to the Hockaday School, a private all girls school in Dallas, to fund science-focused programs; and $30 million to the Dallas-based Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.

On the investment side, she provided early funding to Peloton Therapeutics, which was acquired by Merck & Co. in 2019.

For now, most of her attention is going to Pegasus Park, which seeks to overcome one of Dallas’s most vexing challenges to becoming a biotech hub. Cities like Boston, San Francisco and New York enjoy a concentration of capital, entrepreneurs and academia in a small area. Dallas struggles with dispersion — while the city’s population is 1.3 million, the sprawling Dallas-Fort Worth metro area boasts some 8 million residents.

“Metros that are the size of DFW historically have challenges finding a way to keep these companies clustered together in the same neighbourhood,” said Travis McCready, the head of the life sciences practice in the Americas at JLL, a $7 billion global real estate company.

The 26-acre campus sits near the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, a research institute that employs six Nobel laureates. Several of the professors work on startups that operate out of BioLabs. And the campus is expanding — construction has started on a new wing that will be a laboratory facility.

Steve Case, the billionaire co-founder of AOL, said during a visit to Pegasus Park in September that such hubs can fuel innovation just by bringing together people from different companies and institutions who wouldn’t normally collaborate.

“The very beginning of what’s happening here is quite encouraging and I think bodes well for this next chapter,” said Case, who now runs investment firm Revolution, which focuses on investments in places outside of traditional venture hubs like San Francisco and Boston.

What Dallas lacks, and what Case’s firm is trying to solve, is access to capital. Venture capital funding in Dallas was $157 million in the third quarter, versus $10.2 billion in San Francisco and $3.5 billion in Boston, according to PitchBook data.

BioLabs has been hosting informal meetings at Old Parkland, an office park in Dallas that houses asset management firms, to tout investment opportunities at Pegasus Park. Gabby Everett, a scientist and director of the Dallas Biolabs site, said there are ongoing discussions between some founders and investors.

Hill’s representatives say her involvement in Pegasus Park includes a mix of philanthropic efforts and for-profit investments, but declined to provide a detailed breakdown.

Another developer is looking to cash in on the biotech industry in North Texas. NexPoint founder James Dondero has proposed a $4 billion project that would convert Ross Perot’s former Electronic Data Systems campus in the Dallas suburb of Plano into a life sciences hub. NexPoint received rezoning approval from the Plano city council in November.

The region is already home to major life science firms including Irving-based McKesson Corp. and Galderma, which has its U.S. headquarters in Fort Worth. The DFW airport was one of the first in the country to support cold chain cargo for pharmaceutical shipments.