Paywall.

Who is protesting? Why?

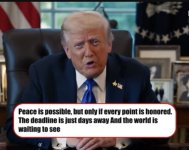

Weird. Still not paywalled for me. Even Donald Trump’s harshest critics — among whom I count myself — have to concede that he has orchestrated a landmark deal in the Middle East that maximized American leverage.

Trump declared it the “end of an age of terror and death,” which is typically overblown and unlikely, given the region’s history.

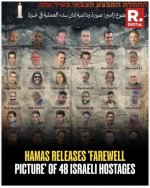

But the explosion of joy, as families are reunited in Israel and in Gaza, suggests there will be resistance on both sides to a resumption of hostilities.

From a Canadian perspective, it has laid bare the flaws and failures in this country’s foreign policy establishment.

The move to unilaterally recognize Palestinian statehood was taken ostensibly because the Israeli government was, in the government’s view, “working methodically to prevent the prospect of a Palestinian state from being established. It is now the avowed policy of the current Israeli government that there be no Palestinian state.”

Yet, point 19 of Trump’s 20-point plan is clear: “While Gaza redevelopment advances, and when the Palestinian Authority reform program is faithfully carried out, the conditions may finally be in place for a credible pathway to Palestinian self-determination and statehood, which we recognize as the aspiration of the Palestinian people.”

Israel may have been dragged kicking and screaming to the table. But it has signed on to a plan that is a damned sight more credible than that proposed by Ottawa, Paris and London, under which statehood recognition was granted in the hope that Hamas would disarm and the Palestinian Authority would finally hold elections.

The foreign policy establishment position — as related by 200 former ambassadors and career diplomats — was that recognition would set the stage for “a serious bilateral negotiation process.”

Instead, it was viewed by Hamas as a validation. Ghazi Hamed, a member of Hamas’s political bureau, told Al Jazeera that recognition “is one of the fruits of October 7th.”

The recognition move may have been merely symbolic, but all terror movements rely on symbolism to disrupt the status quo.

In the course of researching a biography on former justice minister, law professor and human rights icon Irwin Cotler, I talked to John Baird, who was Conservative foreign affairs minister in November 2012, when the United Nations voted to recognize Palestine as a “non-member state.”

Palestinian Authority President then (as now) Mahmoud Abbas, called the resolution the “birth certificate of Palestine” and said a vote for the proposal was the last chance to save a two-state solution.

The resolution passed 138 in favour, and only nine against, one of which was Canada.

Baird was the only foreign minister who showed up to speak against it, “probably the most consequential speech I gave in my political career” and one, it turns out, that was crafted by Cotler, who was at the time a Liberal MP (although he was referred to in Baird’s office as “the associate minister of foreign affairs”).

Baird pointed out that the cornerstone of all peace proposals since UN resolution 181 in 1947 was the need for negotiation and the rejection of one or other side acting unilaterally.

“This resolution will not advance the cause of peace or spur a return to negotiations. Will the Palestinian people be better off as a result? No. On the contrary, this unilateral step will harden positions and raise unrealistic expectations, while doing nothing to improve the lives of the Palestinian people,” he said — a prediction that has been borne out by subsequent events.

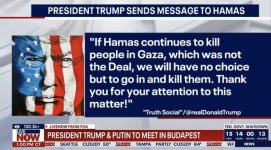

Hamas has only now been forced to make concessions because of losses on the battlefield and because the Americans have leaned hard on the Israelis, Egyptians, Turks and Qataris to recognize the realities in front of them.

On his way to the Summit for Peace in Egypt, Mark Carney put out an eloquent statement, urging all sides to grasp the moment.

“For the Jewish people, this is a moment that holds two truths at once — a grief for what cannot be restored and a fragile light of what might still be repaired,” he said.

He made mention of the Canadians who died on October 7 — Vivian Silver, Netta Epstein, Alexandre Look, Judih Weinstein, Shir Georgy, Ben Mizrachi, and Adi Vital-Kaploun — as well as others with close ties to Canada, like Tiferet Lapidot. And he commended Trump’s leadership in advancing a comprehensive peace plan.

But as Hamas gunmen try to reassert control on the streets of Gaza City and Khan Younis, there needs to be a recognition, at least internally, that Canada got it wrong — that Hamas will never lay down its arms; that the Palestinian Authority will never reform or negotiate, unless there is no alternative.

Cotler told me that in conversations with Abbas that date back to 1977, he noted an evolution in the latter’s thinking that meant by the mid-2000s he may have been disposed toward entering into a peace process with Israel. At the same, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gave a famous foreign policy speech at Bar Ilan in 2009, where he spoke for the first time about a two-state solution.

Both men may have been looking for their place in history.

But both retreated because of domestic pressures — Abbas because Hamas had ejected Fatah from Gaza and forced him to take a more radical position in the West Bank, while Netanyahu was focused on managing an unwieldy coalition that was heavily influenced by orthodox and religious parties after the 2009 election.

The inflection point for a genuine peace passed and has only now come around again. It is regrettable that it is in spite of, rather than because of, Canada.

apple.news