The last one I worked on had bicycle size chain I think. That was pre covid, so I am guessing about the size.Then this would’ve been an ancient. The chain on those gears look like the same size chain on the Honda motorcycle I owned at the time…& if it had any guards over the gears and chains hanging out the side of that toaster, they were long gone. It was pretty cool though.

The Donroe Doctrine

- Thread starter Ron in Regina

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

SovietThen this would’ve been an ancient. The chain on those gears look like the same size chain on the Honda motorcycle I owned at the time…& if it had any guards over the gears and chains hanging out the side of that toaster, they were long gone. It was pretty cool though.

Ok. I’m not up on the ethnicities of toasters, but I remember being pretty impressed by that one. It was truly a mechanical appliance.Soviet

For all, I know this one could’ve started out with a bicycle size chain, etc…& part of keeping it going for decades, was replacing the chain and gears with something heavier or convenient or available, etc…The last one I worked on had bicycle size chain I think. That was pre covid, so I am guessing about the size.

When I went about 15 years ago appliances were RussianOk. I’m not up on the ethnicities of toasters, but I remember being pretty impressed by that one. It was truly a mechanical appliance.

The island lost its main source of fuel in January when the U.S. took control of Venezuela's oil reserves and Washington has since threatened tariffs on countries sending Cuba fuel.

Officials in U.S. President Donald Trump's administration have suggested economic pressure could topple the communist regime, but a Canadian official told a parliamentary committee Tuesday that the Cuban government is stable.

apple.news

apple.news

Officials in U.S. President Donald Trump's administration have suggested economic pressure could topple the communist regime, but a Canadian official told a parliamentary committee Tuesday that the Cuban government is stable.

Canada pledges $8 million in food aid for Cuba as U.S. fuel blockade continues — The Canadian Press

Canada is sending $8 million in food aid to Cuba, where a U.S. oil blockade h

"President Trump's first instinct is always diplomacy," said White House spokesperson Anna Kelly in a statement to Axios, adding: "The President always has a host of options at his disposal, and all of his actions have put America First while making the entire world safer.”

Phew! As a Canadian, now I feel safer. Trump has ‘teased’ (?) for months that Canada should become "the 51st state" and that the U.S. wasn't against annexing Canada? Ok, well, maybe not so much safer as disturbed I guess.

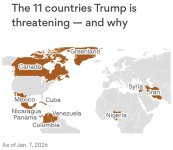

Doesn’t the Greenland thing seem like soooo long ago at this point? Sooo 6 or 7 weeks ago…Despite repeated threats, Canadian Prime Minister Carney has been clear with Trump that Canada has no interest in joining the U.S. Trump has not brought up Canada in the last week since he captured the president of Venezuela, as his focus has been on Mexico, I mean Cuba, I mean Columbia, I mean Panama, I mean Greenland. Yeah, Greenland mostly.

The president’s comments come as relations between the two countries have sunk to one of their lowest points (this could mean the U.S. and pretty much any other country) in an often bitter 67-year history (oh, ok, a qualifier). The US has cranked up pressure on Cuba’s struggling regime after its successful abduction of Venezuelan president and Cuba ally Nicolás Maduro in January.In the latest twist in the ‘Donroe Doctrine’ drama, U.S. President Donald Trump called for a more than 50% increase in the U.S. defense budget by 2027 and threatened to block defense contractors from paying dividends or buying back shares unless they ramped up weapons production…because the United States currently only accounts for roughly 37% to 40% of total global military spending.

In advance of the attack on Caracas, US officials won a promise of cooperation from Maduro’s deputy, Delcy Rodríguez, now Venezuela’s acting president, who has promised to open up the country’s sizeable oil reserves to “foreign” companies.

‘Pressure’ from Washington also led to the departure of the attorney general, Tarek William Saab, and ‘prompted’ Venezuela to cut off oil exports to Cuba. The US has imposed an oil blockade on the island, strangling what was left of the island’s already parlous economy.

Trump’s acquisitive language will provoke worries among Cubans that history is repeating itself: US financial domination of the Cuban economy was one of the main drivers of Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution.

His claim marked a startling departure from previous public statements. The Cuban president, Miguel Díaz-Canel, has previously said that although his government is willing to talk, discussions could not involve Cuba’s internal affairs, and had to come “from a position of equals, with respect for our sovereignty, our independence, and our self-determination”. Good luck with that.

Trump suggests US could carry out ‘friendly takeover’ of Cuba

As tensions between two countries reach new highs, US president says regime is ‘talking with us’

Just curious , how many American troops are on the ground in Venezuela ? Thought so .

Trump has moved to choke off much of Cuba's supply of crude oil, decimating the island's tourist industry and putting mounting pressure on the Cuban government to make some sort of deal with the White House.So… America didn’t invade them and abduct their president, and it hasn’t been shooting missiles at what’s probably drug dealers (though they presented absolutely no proof so far) that might have originated from Venezuela, and America isn’t blockading Venezuelan air & sea traffic then? America and Trump specifically didn’t state that he’s now running Venezuela? Regardless of the number of troops on the ground?

While Trump did not explain what he meant by a friendly takeover, experts on U.S. policy toward Cuba believe the president's tactics are likely more about creating business opportunities for American companies than about toppling the communist regime of President Miguel Díaz-Canel.

Trump said last week he wants to "make a deal" with the Cuban authorities and said Secretary of State Marco Rubio — the son of Cuban immigrants — is leading the talks.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s parents immigrated to the United States from Cuba in 1956. They arrived in Miami more than two years before Fidel Castro took power in 1959. Fulgencio Batista was in control of Cuba in 1956, ruling as a dictator following a coup d'état in March 1952.

Fulgencio Batista was strongly backed by the United States government during his dictatorship in the 1950s. The U.S. provided financial, military, and logistical support, viewing his anti-communist stance as crucial for regional stability and protecting American business interests, which controlled much of Cuba's economy. This is probably just one of those ironic coincidences.

William LeoGrande, a professor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington, D.C., says Trump's objective in Cuba may be similar to what he's aiming to achieve in Venezuela: opening up the country to U.S. business interests like when America backed the Batista dictatorship in Cuba.

Pakistan’s prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif, offered condolences over the killing of the Iranian supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, saying that international law prohibited the targeting of heads of state. South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, questioned the “pre-emptive” justification provided for the war, saying that self-defence was only permitted in response to an armed invasion and that “there can be no military solution to fundamentally political problems”.

Brazil said that it had grave concerns, adding that “the attacks occurred amid a negotiation process between the parties, which is the only viable path to peace”.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, deplored the attacks, which he said were “instigated” by the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. Oman’s foreign minister, Badr Albusaidi, who had said on the eve of the attack that a deal was within reach, said: “I urge the US not to get sucked in further. This is not your war.” Oman downed two drones, while another crashed near its Salalah port on Tuesday, state media said.

Cuba, whose regime is under substantial pressure from Donald Trump, said: “Once again, the US and Israel threaten and seriously endanger regional and international peace, stability, and security.” Malaysia, condemning the attack, said that “disputes must be resolved through dialogue and diplomacy”.

Indonesia, one of the few countries to announce troops for Trump’s Board of Peace’s planned international security force for Gaza, said it “deeply regrets” the failure of the Iran negotiations – while its president offered to travel to Tehran to reopen dialogue. The Indonesian Ulema Council, an organisation of the country’s Muslim clerics, urged their government to withdraw from the Board of Peace in protest.

apple.news

Many other developing nations also lambasted Iran’s attacks on its Gulf neighbours. “This is a war of domination and subordination, therefore it has imperialist undertones and motives,” said Siphamandla Zondi, professor of politics at the University of Johannesburg. “It makes the world unsafe for all of us.”

apple.news

Many other developing nations also lambasted Iran’s attacks on its Gulf neighbours. “This is a war of domination and subordination, therefore it has imperialist undertones and motives,” said Siphamandla Zondi, professor of politics at the University of Johannesburg. “It makes the world unsafe for all of us.”

Commentators said Europe had shown double standards, stridently defending international law when it came to Trump’s attempts to annex Greenland but muted in the case of this war.

Amitav Acharya, author of The Once and Future Global Order, said that in the past, the US had sought influence and legitimacy. Now, the US acted solely through coercion, even as Chinese soft power was gaining, with Beijing offering investment to developing countries. He said that Russia, too, would benefit, as Iran and other Trump foreign policy shocks took the focus away from Ukraine.

“Many countries in the global south are going to look for a coalition of powers that will stand up to the United States, as the United States is seen as so aggressive, so imperial,” said Acharya. Some commentators emphasised that criticism of the war did not mean support of the Iranian regime.

The Trump administration sought neither the approval of the UN security council – as Washington attempted for the Iraq war in 2003 – – nor even the approval of elected representatives at home, analysts said. Oliver Stuenkel, professor of International Relations at Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV) in São Paulo, said that there was fear in Latin America that, emboldened by his actions in Venezuela and Iran, Trump would attempt to target Cuba.

“There is a profound sense that international law is being eroded more systematically, and that has, I think, profound consequences for many countries in the global south, which are militarily weak and vulnerable, have rich natural resources, and have long made a bet on international rules and norms,” said Stuenkel. Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the US, said the US was negotiating with Iran in bad faith, as it did last year, using talks as a smokescreen to complete preparations to attack.

“Who can trust the Trump administration now? It acts unilaterally in total defiance of international law and any norms of diplomacy,” said Lodhi. “This will come back to haunt them.” Israel and the US intensified their attacks on Iran on Tuesday, launching waves of strikes targeting command and control facilities, strategic state offices and missile launch sites as Donald Trump said he had rejected what he claimed was an attempt by Tehran to restart negotiations.

Despite acute international fears, there appeared little chance of any de-escalation of the conflict as violence and chaos continued across a fast-widening swathe of the Middle East for a fourth day. “Their air defense, Air Force, Navy and Leadership is gone. They want to talk. I said ‘Too Late!’,” the US president wrote on his Truth Social platform, saying the US was prepared “to go far longer” than a four to five-week war against Iran.

apple.news

apple.news

Brazil said that it had grave concerns, adding that “the attacks occurred amid a negotiation process between the parties, which is the only viable path to peace”.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, deplored the attacks, which he said were “instigated” by the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. Oman’s foreign minister, Badr Albusaidi, who had said on the eve of the attack that a deal was within reach, said: “I urge the US not to get sucked in further. This is not your war.” Oman downed two drones, while another crashed near its Salalah port on Tuesday, state media said.

Cuba, whose regime is under substantial pressure from Donald Trump, said: “Once again, the US and Israel threaten and seriously endanger regional and international peace, stability, and security.” Malaysia, condemning the attack, said that “disputes must be resolved through dialogue and diplomacy”.

Indonesia, one of the few countries to announce troops for Trump’s Board of Peace’s planned international security force for Gaza, said it “deeply regrets” the failure of the Iran negotiations – while its president offered to travel to Tehran to reopen dialogue. The Indonesian Ulema Council, an organisation of the country’s Muslim clerics, urged their government to withdraw from the Board of Peace in protest.

‘Imperialist undertones’: global south condemns US-Israeli war with Iran — Guardian US

China calls it unacceptable to ‘kill leader of sovereign state’, while South Africa questions ‘pre-emptive’ justification

Commentators said Europe had shown double standards, stridently defending international law when it came to Trump’s attempts to annex Greenland but muted in the case of this war.

Amitav Acharya, author of The Once and Future Global Order, said that in the past, the US had sought influence and legitimacy. Now, the US acted solely through coercion, even as Chinese soft power was gaining, with Beijing offering investment to developing countries. He said that Russia, too, would benefit, as Iran and other Trump foreign policy shocks took the focus away from Ukraine.

“Many countries in the global south are going to look for a coalition of powers that will stand up to the United States, as the United States is seen as so aggressive, so imperial,” said Acharya. Some commentators emphasised that criticism of the war did not mean support of the Iranian regime.

The Trump administration sought neither the approval of the UN security council – as Washington attempted for the Iraq war in 2003 – – nor even the approval of elected representatives at home, analysts said. Oliver Stuenkel, professor of International Relations at Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV) in São Paulo, said that there was fear in Latin America that, emboldened by his actions in Venezuela and Iran, Trump would attempt to target Cuba.

“There is a profound sense that international law is being eroded more systematically, and that has, I think, profound consequences for many countries in the global south, which are militarily weak and vulnerable, have rich natural resources, and have long made a bet on international rules and norms,” said Stuenkel. Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the US, said the US was negotiating with Iran in bad faith, as it did last year, using talks as a smokescreen to complete preparations to attack.

“Who can trust the Trump administration now? It acts unilaterally in total defiance of international law and any norms of diplomacy,” said Lodhi. “This will come back to haunt them.” Israel and the US intensified their attacks on Iran on Tuesday, launching waves of strikes targeting command and control facilities, strategic state offices and missile launch sites as Donald Trump said he had rejected what he claimed was an attempt by Tehran to restart negotiations.

Despite acute international fears, there appeared little chance of any de-escalation of the conflict as violence and chaos continued across a fast-widening swathe of the Middle East for a fourth day. “Their air defense, Air Force, Navy and Leadership is gone. They want to talk. I said ‘Too Late!’,” the US president wrote on his Truth Social platform, saying the US was prepared “to go far longer” than a four to five-week war against Iran.

Middle East attacks intensify as Trump says he rejects Iran’s attempt to talk — Guardian US

US president claims ‘they want to talk. I said: Too Late!’, while Rubio threatens the ‘hardest hits are yet to come’

The military released no details on the operations but suggested in a statement that it was an extension of strikes carried out by the Trump administration against suspected drug trafficking organizations in the region. During Rubio's trip to Ecuador, the U.S. designated two criminal groups in Ecuador, Los Lobos and Los Choneros, as terrorist organizations. Until now, the U.S. had conducted military operations near Ecuador but had not publicly disclosed anything inside the country.

After the operation to capture Maduro, Trump did not rule out using military force against targets in other countries in the name of combatting drug trafficking. The expectation, however, had been that Trump would conduct strikes in Mexico and Colombia, both of which have a more significant role in the drug trade.

apple.news

apple.news

After the operation to capture Maduro, Trump did not rule out using military force against targets in other countries in the name of combatting drug trafficking. The expectation, however, had been that Trump would conduct strikes in Mexico and Colombia, both of which have a more significant role in the drug trade.

US launches military operations in Ecuador — POLITICO

The joint military operation with Ecuador targeted what the U.S. called "designated terrorist organizations" in the country.

May have been Equador that was going to legalize cocaine and market it accordingly.

It's not like they can eradicate the plants from growing

It's not like they can eradicate the plants from growing

Three constants. . .May have been Equador that was going to legalize cocaine and market it accordingly.

It's not like they can eradicate the plants from growing

1. People will use substances to alter their brain chemistry/mood/emotions (drugs).

2. People will trade valuables for sex (prostitution).

3. People will indulge in the risk/reward sensation of wagering valuables on random events or competitions (gambling).

Every government has, at one point or another, tried to forbid one or more of these activities.

Every such attempt has failed utterly.

Legalize 'em, tax 'em, and use the tax money to ameliorate the negative effects.

Going after the source doesn't impact the dopamine lust of the user.Three constants. . .

1. People will use substances to alter their brain chemistry/mood/emotions (drugs).

2. People will trade valuables for sex (prostitution).

3. People will indulge in the risk/reward sensation of wagering valuables on random events or competitions (gambling).

Every government has, at one point or another, tried to forbid one or more of these activities.

Every such attempt has failed utterly.

Legalize 'em, tax 'em, and use the tax money to ameliorate the negative effects.

The term of the “Shield of the Americas (plural)” got mentioned today with little to no details whatsoever beyond complete vaguery, & supposedly there’s gonna be some kind of announcement in less than 48 hours on Saturday about this.

www.youtube.com

(YouTube & What is the Shield of the Americas, Kristi Noem's next venture?)

www.youtube.com

(YouTube & What is the Shield of the Americas, Kristi Noem's next venture?)

This is also my experience so far too, to be honest. There is almost nothing out there with respect to this “Shield of the Americas (plural)” at this point.

This is early March 2026 right now, & here’s Google AI trying to guess at an answer to my question of “What is the Shield of the Americas?”

Hold onto your hats folks, as this one feels like it’s gonna be a real doozy…

www.chosun.com

www.chosun.com

What is the Shield of the Americas, Kristi Noem's next venture?

What is the Shield of the Americas? Here's what we know.READ: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2026/03/05/shield-of-the-americas-initiative-krist...

This is also my experience so far too, to be honest. There is almost nothing out there with respect to this “Shield of the Americas (plural)” at this point.

This is early March 2026 right now, & here’s Google AI trying to guess at an answer to my question of “What is the Shield of the Americas?”

Hold onto your hats folks, as this one feels like it’s gonna be a real doozy…

Trump Revives Monroe Doctrine at Latin America Summit

Trump Revives Monroe Doctrine at Latin America Summit U.S. intensifies anti-cartel operations as Trump allies gather to counter Pink Tide leftist blocs

US President Donald Trump hosted Latin American leaders (some of them, anyway, of the correct flavour) on Saturday at his Miami-area golf club for what the White House called the "Shield of the Americas" summit.The term of the “Shield of the Americas (plural)” got mentioned today with little to no details whatsoever beyond complete vaguery, & supposedly there’s gonna be some kind of announcement in less than 48 hours on Saturday about this.

Trump appeared briefly at the summit, fulfilling his commitment to Western Hemisphere politics, despite the current war unfolding in Iran, where the US is now involved. During his appearance, Trump signed a proclamation launching the regional coalition.

In attendance were the leaders of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guyana, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Notably, the leaders of Brazil, Mexico and Colombia were not in attendance. The three region heavyweights are currently led by left-leaning presidents.

Notably, the leaders of Brazil, Mexico and Colombia were not in attendance. The three region heavyweights are currently led by left-leaning presidents.Donald Trump Refuses to Learn Spanish at Shield of the Americas Event — TMZ

Donald Trump says he's too busy to learn Spanish ... even while he works on a new initiative drawing Latin America deeper into the U.S.A.'s sphere of influence.

The White House has billed the summit as the founding of the "Americas Counter Cartel Coalition" which they described as a new military partnership with leaders in the region, or at least some of them. Notably, the "Shield of the Americas" will have Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem as its special envoy.

Kristi Noem appears with Trump in new ‘Shield of the Americas’ role - days after he fired her from DHS — The Independent

Corey Lewandowski, the DHS staffer Noem is rumored to be having an affair with, was seen nearby

Noem made no mention of her swift transfer of roles but pointed to her experience in securing the US borders. “Now that America is secure, and our borders are secure, we want to focus on our neighbors and help our neighbors with their borders and the challenges they have.”

Trump convenes ‘Shield of Americas’ summit with 12 Latin American leaders — Guardian US

President called for regional cooperation in western hemisphere to counter China economic and political interests

"We're working with you to do whatever we have to do. We'll use missiles. You want us to use a missile? They're extremely accurate," Trump said. "'Piu,' right into the living room," he said, mimicking the sound of missiles.

“That's the end of that cartel person. But we'll do whatever you need," the US president added.

'Shield of the Americas': Trump launches regional coalition — DW

Trump said Latin America's "tremendous potential" could only be fulfilled if cartels and criminal gangs were defeated.

So…imminent action against Cuba because of drugs or cartels?

I guess Cuba is a neighbour of America, and it is in the western hemisphere, so it does deserve Kristi Gnome’s attention since she is done in Minneapolis, etc…

Some of us have been pushing that for a long time. But our government went on a multi million spending spree to give addicts free drugs, and in typical poliricspeek, call it harm reduction. Crickets for treatment. AS they were told, the plan was a spectacular failure in all but employing social workers with no other job qualifications. The program is now cancelled. So much money for meth, and none for insulin. Makes one wonder just where they get their cash from.Three constants. . .

1. People will use substances to alter their brain chemistry/mood/emotions (drugs).

2. People will trade valuables for sex (prostitution).

3. People will indulge in the risk/reward sensation of wagering valuables on random events or competitions (gambling).

Every government has, at one point or another, tried to forbid one or more of these activities.

Every such attempt has failed utterly.

Legalize 'em, tax 'em, and use the tax money to ameliorate the negative effects.

Oh, I'm sure that "Canadian Official" knows what he's talking about. He obviously hasn't seen the video by Rebel News about Cuba. They sent people there under cover to show what Cuba was actually like. It was really interesting, that's for sure. Tourists don't generally see the poorer sections of Havana or other parts of the country.The island lost its main source of fuel in January when the U.S. took control of Venezuela's oil reserves and Washington has since threatened tariffs on countries sending Cuba fuel.

Officials in U.S. President Donald Trump's administration have suggested economic pressure could topple the communist regime, but a Canadian official told a parliamentary committee Tuesday that the Cuban government is stable.

Canada pledges $8 million in food aid for Cuba as U.S. fuel blockade continues — The Canadian Press

Canada is sending $8 million in food aid to Cuba, where a U.S. oil blockade happle.news