To Strengthen Democracy, Welcome New Chinese Immigrants

Falun Gong practitioners take part in a parade to commemorate the 23rd anniversary of the persecution of the spiritual discipline in China, in New York’s Chinatown on July 10, 2022. (Larry Dye/The Epoch Times)

Thinking About China

Anders CorrNovember 15, 2022 Updated: November 16, 2022

Commentary

Last month, Xi Jinping got his third-and-forever term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He used the opportunity to subdue talk of China’s sputtering economy and accelerate preparations for war. Many of China’s technological and entrepreneurial elites are responding by fleeing the country. They want new passports and lives abroad.

With Hong Kong no longer safe, they head to places like the United States, Europe, Singapore, and Caribbean countries whose printers churn passports like so many hundred-dollar bills: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Saint Kitts, and Nevis.

Wealthy Chinese immigrants can bring their technological and scientific expertise to new countries, and sometimes invest millions of dollars for the privilege.

Others, particularly Uyghurs, Falun Gong, Tibetans, Hongkongers, and human rights defenders, have a legal right to asylum due to their targeted persecution. They should be welcomed purely on the basis of ethics, which builds on the economic rationale.

In the United Kingdom, rumors are spreading of a wave of Chinese real estate buyers. That’s good for Britain, as deep Chinese wallets will boost home prices and help the building industry and economic recovery.

And who could blame wealthy and talented Chinese for wanting to leave a totalitarian and genocidal state that has undergone three years of extreme COVID-19 lockdowns, with no end in sight, not to mention Xi’s communism and nuclear saber-rattling?

A Chinese paramilitary policeman stands guard on the Bund waterfront during China’s National Day celebrations in Shanghai on Oct. 1, 2022. (Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

The Chinese quite reasonably want to escort their families and money to freer, safer, and more welcoming climes. The United States is a country of immigrants built on exactly these principles. New anti-communist Chinese immigrants will fit right in, and if the Russians who fled the Soviets are any indication, many will eventually vote Republican.

Refugees from China are still at risk. Beijing knows they are fleeing and watches carefully for any signs of movement. The CCP’s capital controls are draconian. One misstep, for example, transferring too much money abroad at one time, or moving too many family members outside China, can trigger the seizure of bank accounts, denial of exit visas, and confiscation of passports.

The regime’s extralegal police stations abroad can abduct and rendition refugees back to China. Even some democratic governments have extradition treaties with China and its “autonomous” regions, Hong Kong and Macau, jeopardizing many connecting flights in not only Asia and the Middle East, but throughout the world.

Nevertheless, the wealthy refugee flow accelerates because Chinese elites see the CCP as rupturing a long-held agreement to let the wealthy build their capital in exchange for letting the CCP build, and abuse, its power.

Xi’s promotion of communist economic principles—including a bigger role for government and a smaller one for the market, along with his “common prosperity” push for more social services and less reliance on monetary incentives to work—will hurt economic growth and the pocketbooks of China’s middle class. To put it nicely, Xi’s overbearing political system is fueling economic doldrums, disillusionment, and unemployment.

When Chinese citizens don’t leave the country physically, they can check out through more subtle forms of noncooperation, like the “lying flat” movement, and turn to recreation. The Chinese, who previously strived to achieve national objectives through hard personal work, are happily starting to play more ping pong and badminton.

Tech analyst Li Yuan at The New York Times has a particularly astute analysis of the perceptions driving the flight of technology talent from China. It centers on dictator Xi, who “left the private sector largely alone in his first term, when he was busy consolidating his power within the party and the military.” By the second term, starting in 2017, “Xi kept private enterprises on a much tighter leash.”

Xi’s third term is turning more militaristic in nature. Now that he consolidated his political and economic power within China, epitomized by the manhandling of former leader Hu Jintao at last month’s congress, Xi apparently thinks the time has come to accelerate power projection abroad.

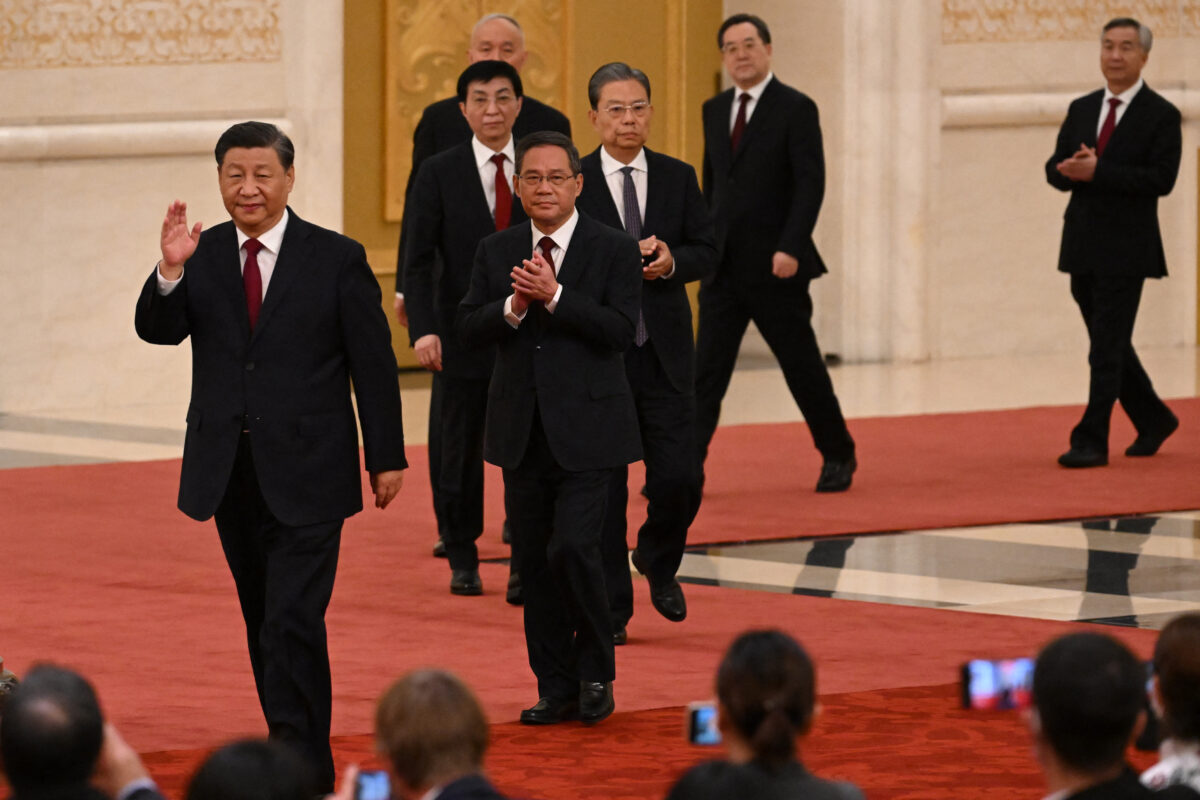

China’s leader Xi Jinping (front) walks with members of the Chinese Communist Party’s new Politburo Standing Committee, the nation’s top decision-making body, as they meet the media in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oct. 23, 2022. (Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images)

And Xi is not the only problem. His seven-member politburo, which replaced moderates and economic expertise with Xi’s yes-men, indicates that his rule will be increasingly arbitrary and uninformed. Some call the politburo, which includes a veteran of the 1979 invasion of Vietnam, more of a war council.

Without ranking moderates, the chance of Xi’s removal is almost zero, and the one for a return to astronomical economic growth is nearly as bad. Shortly after the congress, Chinese stocks and currency fell precipitously in value.

There is a silver lining. Xi is becoming adept at scoring his own goals. Those who love freedom can benefit by “assisting” him in this self-defeating behavior and hiring away his disillusioned team.

We can do so by facilitating Chinese scientific, economic, and political émigrés who demonstrate commitment to their new countries by successfully moving their money and families to freedom. Anything we do to speed that process is a win for justice and liberty.

Anders Corr has a bachelor’s/master’s in political science from Yale University (2001) and a doctorate in government from Harvard University (2008). He is a principal at Corr Analytics Inc., publisher of the Journal of Political Risk, and has conducted extensive research in North America, Europe, and Asia. His latest books are “The Concentration of Power: Institutionalization, Hierarchy, and Hegemony” (2021) and “Great Powers, Grand Strategies: the New Game in the South China Sea” (2018).

To Strengthen Democracy, Welcome New Chinese Immigrants

Commentary Last month, Xi Jinping got his third-and-forever term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). ...

www.theepochtimes.com

www.theepochtimes.com