Science & Environment

- Thread starter socratus

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Quebec man stung by scorpion hiding in Costco bananas

Author of the article enette Wilford

enette Wilford

Published Mar 26, 2024 • Last updated 1 day ago • 2 minute read

A man in Laval, Que., says he was stung by a scorpion concealed in a bunch of bananas he had purchased at Costco.

Benoit Sanscartier had bought groceries from the Costco location in Boisbriand, just west of Laval, when the shocking incident occurred.

“I removed the paper around the bananas and I got stung by the scorpion,” Sanscartier told TVA Nouvelles.

He added that the sting hurt badly, describing it as “twice the pain of a wasp sting.”

University of Montreal entomologist Etienne Normandin told the outlet that these scorpions “are imported from the southern United States or Central America and are frequently found on bananas or grapes.”

The scorpion found in Sanscartier’s Costco bananas are believed to have come from Guatemala.

Sanscartier called 811 immediately after he was bitten but after more than an hour of waiting, he went to the hospital.

When Sanscartier reached out to Costco, they told him they only had a protocol in place for employees.

“It’s the first time they’ve seen that for a client,” he said.

Sanscartier now keeps the scorpion in a jar.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has launched an investigation into how the scorpion got all the way to Canada.

However, Normandin explained that in some South American countries, the items are placed in carts or in large warehouses where scorpions “can sneak in and be transported here.”

He added: “In a few days, the scorpion can survive the cold, because they are kept in stable conditions.”

Toronto Sun columnist Dr. Sylvain Charlebois noted this isn’t the first time scorpions have been found hiding in bananas in Canada.

“Scorpions have been found before in Canada, concealed in bananas, in 2017 in Nova Scotia, and Montreal in 2023,” he posted on X.

The Sun reached out to Costco but did not get a response in time for publication.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article

Published Mar 26, 2024 • Last updated 1 day ago • 2 minute read

A man in Laval, Que., says he was stung by a scorpion concealed in a bunch of bananas he had purchased at Costco.

Benoit Sanscartier had bought groceries from the Costco location in Boisbriand, just west of Laval, when the shocking incident occurred.

“I removed the paper around the bananas and I got stung by the scorpion,” Sanscartier told TVA Nouvelles.

He added that the sting hurt badly, describing it as “twice the pain of a wasp sting.”

University of Montreal entomologist Etienne Normandin told the outlet that these scorpions “are imported from the southern United States or Central America and are frequently found on bananas or grapes.”

The scorpion found in Sanscartier’s Costco bananas are believed to have come from Guatemala.

Sanscartier called 811 immediately after he was bitten but after more than an hour of waiting, he went to the hospital.

When Sanscartier reached out to Costco, they told him they only had a protocol in place for employees.

“It’s the first time they’ve seen that for a client,” he said.

Sanscartier now keeps the scorpion in a jar.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has launched an investigation into how the scorpion got all the way to Canada.

However, Normandin explained that in some South American countries, the items are placed in carts or in large warehouses where scorpions “can sneak in and be transported here.”

He added: “In a few days, the scorpion can survive the cold, because they are kept in stable conditions.”

Toronto Sun columnist Dr. Sylvain Charlebois noted this isn’t the first time scorpions have been found hiding in bananas in Canada.

“Scorpions have been found before in Canada, concealed in bananas, in 2017 in Nova Scotia, and Montreal in 2023,” he posted on X.

The Sun reached out to Costco but did not get a response in time for publication.

Quebec man stung by scorpion hiding in Costco bananas

A man in Laval, Que., was stung by a scorpion concealed in a bunch of bananas he had purchased at Costco.

Bird flu detected in milk from dairy cows in Texas and Kansas

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Andrew Jeong, The Washington Post

Published Mar 26, 2024 • 2 minute read

Bird-Flu-Livestock

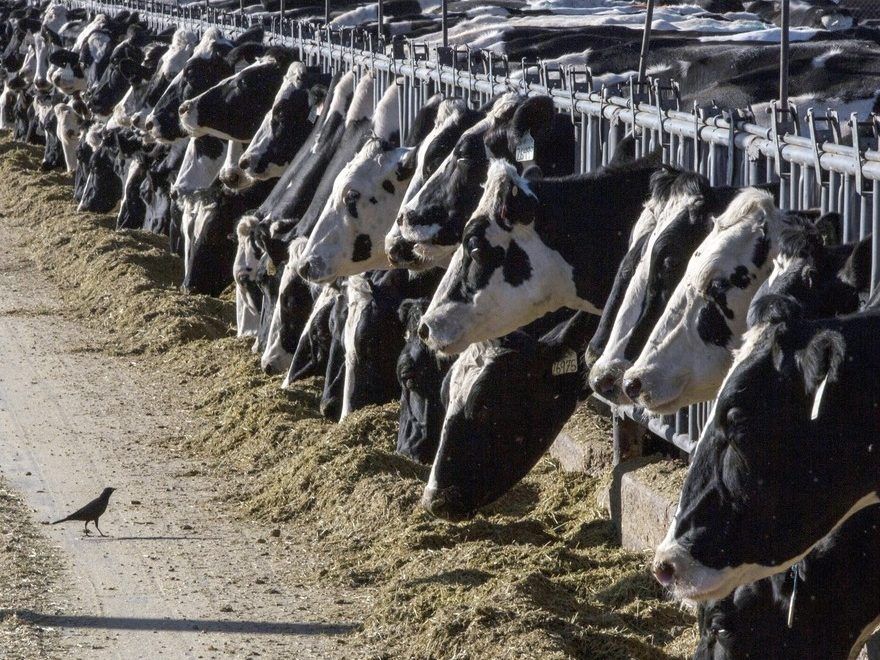

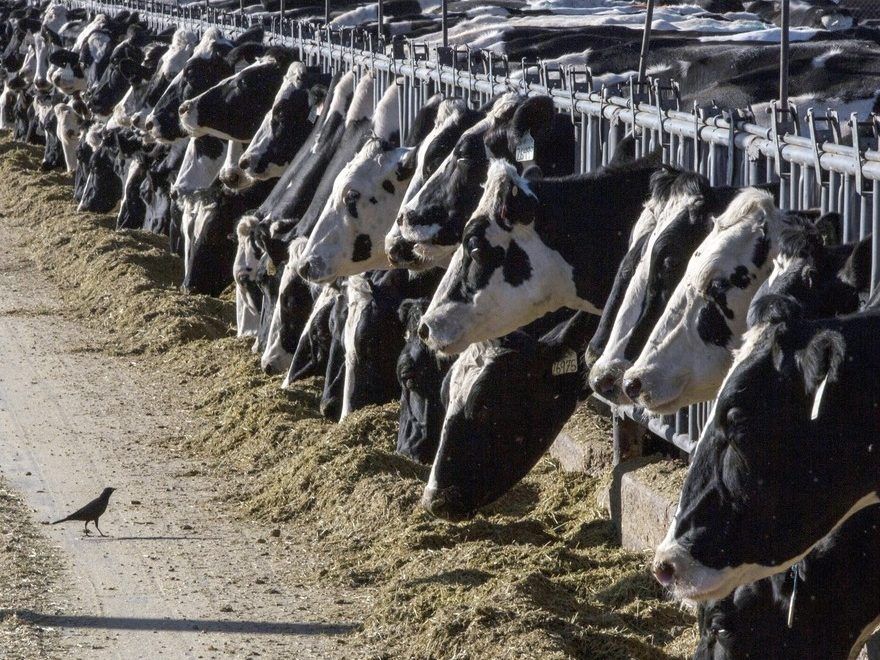

The U.S. Department of Agriculture said Monday, March 25, 2024, that milk from dairy cows in Texas and Kansas has tested positive for bird flu.

Milk and nasal swab samples from sick cattle on at least two dairy farms in Texas and two in Kansas have tested positive for bird flu, according to federal and state officials.

Agencies are moving quickly to conduct more testing for the illness – known as highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI – the U.S. Department of Agriculture said in a news release Monday.

Cattle are showing flu-like symptoms and lactating discolored milk, Texas state officials said. Wild migratory birds are probably the source of infection, federal officials added, pointing to reports that farms have found dead wild birds on their properties.

The announcement comes after Minnesota officials reported the first infection of avian flu among livestock in the United States last week, when a juvenile goat living on a farm with infected poultry tested positive.

The infections among cattle pose minimal risk to human food safety or milk supply and prices, officials said. Milk from sick cattle is being diverted or destroyed. Pasteurization – a heating treatment that kills pathogens – is required for milk involved in interstate commerce, greatly reducing the possibility that infected milk enters the food supply, they added.

The milk samples that tested positive for bird flu were unpasteurized, according to federal officials.

“There is no threat to the public and there will be no supply shortages,” Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller said in a news release. “No contaminated milk is known to have entered the food chain; it has all been dumped. In the rare event that some affected milk enters the food chain, the pasteurization process will kill the virus.”

Officials have long cautioned consumers to avoid raw milk, or unpasteurized milk, which can be sold within some states, including Texas and Kansas. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls raw milk “one of the riskiest foods” and says it is “linked to a variety of foodborne illnesses.”

Texas requires dairy farms selling raw milk to have it tested every three months. Kansas requires raw milk sales to “take place at the farm where it was produced,” while any advertising and any containers must plainly state that it is raw milk.

The loss of milk from symptomatic cows is too limited to have a major impact on milk supply, federal officials said, meaning “there should be no impact on the price of milk or other dairy products.”

Federal and state officials are investigating primarily older cows in Texas, Kansas and New Mexico. Iowa officials are also “actively monitoring this evolving situation.”

Unlike outbreaks among poultry, bird flu infections among mammals are expected not to require massive culling efforts, officials said. In rare cases, avian flu has jumped from birds to humans, most notably during an avian influenza outbreak in Hong Kong in 1997, according to the World Health Organization.

Brian Hoefs, a veterinarian and the executive director of the Minnesota Board of Animal Health, said last week that the kid goat’s bird flu infection “highlights the possibility of the virus infecting other animals on farms with multiple species.”

“Thankfully, research to-date has shown mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, which means they’re unlikely to spread HPAI further,” he added at the time.

Miller said he does not expect a “need to depopulate dairy herds,” and that the affected cattle are “expected to fully recover.”

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Andrew Jeong, The Washington Post

Published Mar 26, 2024 • 2 minute read

Bird-Flu-Livestock

The U.S. Department of Agriculture said Monday, March 25, 2024, that milk from dairy cows in Texas and Kansas has tested positive for bird flu.

Milk and nasal swab samples from sick cattle on at least two dairy farms in Texas and two in Kansas have tested positive for bird flu, according to federal and state officials.

Agencies are moving quickly to conduct more testing for the illness – known as highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI – the U.S. Department of Agriculture said in a news release Monday.

Cattle are showing flu-like symptoms and lactating discolored milk, Texas state officials said. Wild migratory birds are probably the source of infection, federal officials added, pointing to reports that farms have found dead wild birds on their properties.

The announcement comes after Minnesota officials reported the first infection of avian flu among livestock in the United States last week, when a juvenile goat living on a farm with infected poultry tested positive.

The infections among cattle pose minimal risk to human food safety or milk supply and prices, officials said. Milk from sick cattle is being diverted or destroyed. Pasteurization – a heating treatment that kills pathogens – is required for milk involved in interstate commerce, greatly reducing the possibility that infected milk enters the food supply, they added.

The milk samples that tested positive for bird flu were unpasteurized, according to federal officials.

“There is no threat to the public and there will be no supply shortages,” Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller said in a news release. “No contaminated milk is known to have entered the food chain; it has all been dumped. In the rare event that some affected milk enters the food chain, the pasteurization process will kill the virus.”

Officials have long cautioned consumers to avoid raw milk, or unpasteurized milk, which can be sold within some states, including Texas and Kansas. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls raw milk “one of the riskiest foods” and says it is “linked to a variety of foodborne illnesses.”

Texas requires dairy farms selling raw milk to have it tested every three months. Kansas requires raw milk sales to “take place at the farm where it was produced,” while any advertising and any containers must plainly state that it is raw milk.

The loss of milk from symptomatic cows is too limited to have a major impact on milk supply, federal officials said, meaning “there should be no impact on the price of milk or other dairy products.”

Federal and state officials are investigating primarily older cows in Texas, Kansas and New Mexico. Iowa officials are also “actively monitoring this evolving situation.”

Unlike outbreaks among poultry, bird flu infections among mammals are expected not to require massive culling efforts, officials said. In rare cases, avian flu has jumped from birds to humans, most notably during an avian influenza outbreak in Hong Kong in 1997, according to the World Health Organization.

Brian Hoefs, a veterinarian and the executive director of the Minnesota Board of Animal Health, said last week that the kid goat’s bird flu infection “highlights the possibility of the virus infecting other animals on farms with multiple species.”

“Thankfully, research to-date has shown mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, which means they’re unlikely to spread HPAI further,” he added at the time.

Miller said he does not expect a “need to depopulate dairy herds,” and that the affected cattle are “expected to fully recover.”

Bird flu detected in milk from dairy cows in Texas and Kansas

Agencies are moving quickly to conduct more testing for the illness.

Measles cases in Canada are increasing, Canada’s chief public health officer warns

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Nicole Ireland

Published Mar 27, 2024 • 2 minute read

Tam issued a statement Wednesday saying the Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 measles cases in Canada so far this year.

Tam issued a statement Wednesday saying the Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 measles cases in Canada so far this year.

The number of confirmed measles cases in Canada so far this year is more than three times higher than all infections recorded in 2023, the country’s chief public health officer said as she urged people to ensure their vaccinations are up to date.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 confirmed cases across the country in 2024, Dr. Theresa Tam said on Wednesday.

Tam said she is concerned that not enough school-aged children have been adequately vaccinated against the highly contagious virus.

“I strongly advise parents or caregivers to ensure that children in their care have received all measles vaccines according to schedule,” she said in an interview.

Those who aren’t sure about their child’s vaccination history should speak to their health-care provider or local public health agency, Tam said.

The timing of the doses varies by province and territory, but generally children get their first doses of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine at 12 to 15 months of age and then a second dose before they start school.

“The measles-containing vaccines are very effective. (The) benefits far outweigh the risks,” Tam said.

“There’s no reason why children — who could get quite seriously sick from this illness — should be getting it because it’s vaccine-preventable,” she said.

Quebec has had 28 confirmed cases this year — the most in the country, Tam said. Ontario has had 10 cases; B.C. and Saskatchewan have had one case each.

The majority of people who have been infected with measles in Canada were unvaccinated and most of them were children.

Seven people have been hospitalized due to measles this year, Tam said.

She said although some people have been infected while travelling internationally, others have caught measles in Canada.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has previously urged people to check their measles vaccination status before the busy March Break travel season.

On Wednesday, Tam said it’s difficult to tell at this point if March break travel has contributed to an increase in cases, but wanted to get the message out again as people are preparing for family gatherings and religious celebrations.

The rise in measles this year is likely caused by increased measles activity worldwide, combined with “suboptimal vaccine uptake nationally,” Tam said.

She said there may have been a decrease in access to routine vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic, but local public health agencies have been “trying very hard to do catch up.”

There has been a recent “upswing in public interest in getting the vaccine, which is great,” she said.

Symptoms of measles include fever, red watery eyes, runny nose and a cough at first. Those symptoms are followed by a red rash that starts on the face and moves to other parts of the body, the Public Health Agency of Canada said in a statement.

“Measles is more than a rash. Infection can lead to rare, but severe complications, including deafness and brain injury caused by inflammation of the brain, and can even be fatal,” the statement said.

A 95 per cent vaccination rate is needed to give communities herd immunity against measles.

The most recent available national data, which is from 2021, showed that 79 per cent of children had two doses of measles vaccine by age seven.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Nicole Ireland

Published Mar 27, 2024 • 2 minute read

Tam issued a statement Wednesday saying the Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 measles cases in Canada so far this year.

Tam issued a statement Wednesday saying the Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 measles cases in Canada so far this year.

The number of confirmed measles cases in Canada so far this year is more than three times higher than all infections recorded in 2023, the country’s chief public health officer said as she urged people to ensure their vaccinations are up to date.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 confirmed cases across the country in 2024, Dr. Theresa Tam said on Wednesday.

Tam said she is concerned that not enough school-aged children have been adequately vaccinated against the highly contagious virus.

“I strongly advise parents or caregivers to ensure that children in their care have received all measles vaccines according to schedule,” she said in an interview.

Those who aren’t sure about their child’s vaccination history should speak to their health-care provider or local public health agency, Tam said.

The timing of the doses varies by province and territory, but generally children get their first doses of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine at 12 to 15 months of age and then a second dose before they start school.

“The measles-containing vaccines are very effective. (The) benefits far outweigh the risks,” Tam said.

“There’s no reason why children — who could get quite seriously sick from this illness — should be getting it because it’s vaccine-preventable,” she said.

Quebec has had 28 confirmed cases this year — the most in the country, Tam said. Ontario has had 10 cases; B.C. and Saskatchewan have had one case each.

The majority of people who have been infected with measles in Canada were unvaccinated and most of them were children.

Seven people have been hospitalized due to measles this year, Tam said.

She said although some people have been infected while travelling internationally, others have caught measles in Canada.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has previously urged people to check their measles vaccination status before the busy March Break travel season.

On Wednesday, Tam said it’s difficult to tell at this point if March break travel has contributed to an increase in cases, but wanted to get the message out again as people are preparing for family gatherings and religious celebrations.

The rise in measles this year is likely caused by increased measles activity worldwide, combined with “suboptimal vaccine uptake nationally,” Tam said.

She said there may have been a decrease in access to routine vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic, but local public health agencies have been “trying very hard to do catch up.”

There has been a recent “upswing in public interest in getting the vaccine, which is great,” she said.

Symptoms of measles include fever, red watery eyes, runny nose and a cough at first. Those symptoms are followed by a red rash that starts on the face and moves to other parts of the body, the Public Health Agency of Canada said in a statement.

“Measles is more than a rash. Infection can lead to rare, but severe complications, including deafness and brain injury caused by inflammation of the brain, and can even be fatal,” the statement said.

A 95 per cent vaccination rate is needed to give communities herd immunity against measles.

The most recent available national data, which is from 2021, showed that 79 per cent of children had two doses of measles vaccine by age seven.

Measles cases in Canada are increasing, Canada’s chief public health officer warns

The Public Health Agency of Canada is aware of 40 confirmed cases across the country in 2024, Dr. Theresa Tam said on Wednesday.

Largest fresh egg producer in U.S. has found bird flu in chickens at Texas, Michigan plants

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Ken Miller

Published Apr 02, 2024 • 2 minute read

The largest producer of fresh eggs in the U.S. said Tuesday it had temporarily halted production at a Texas plant after bird flu was found in chickens, and officials said the virus had also been detected at a poultry facility in Michigan.

Ridgeland, Mississippi-based Cal-Maine Foods, Inc. said in a statement that approximately 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets, about 3.6% of its total flock, were destroyed after the infection, avian influenza, was found at a facility in Parmer County, Texas.

The plant is on the Texas-New Mexico border in the Texas Panhandle about 85 miles (137 kilometers) southwest of Amarillo and about 370 miles (595 kilometers) northwest of Dallas. Cal-Maine said it sells most of its eggs in the Southwestern, Southeastern, Midwestern and mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.

“The Company continues to work closely with federal, state and local government officials and focused industry groups to mitigate the risk of future outbreaks and effectively manage the response,” the statement said.

“Cal-Maine Foods is working to secure production from other facilities to minimize disruption to its customers,” the statement said.

The company said there is no known bird flu risk associated with eggs that are currently in the market and no eggs have been recalled.

Eggs that are properly handled and cooked are safe to eat, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The announcement by Cal-Maine comes a day after state health officials said a person had been diagnosed with bird flu after being in contact with cows presumed to be infected, and that the risk to the public remains low. The human case in Texas marks the first known instance globally of a person catching this version of bird flu from a mammal, federal health officials said.

In Michigan, Michigan State University’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory has detected bird flu in a commercial poultry facility in Ionia County, according to the Michigan’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

The county is about 100 miles (161 kilometers) northwest of Detroit.

The department said it received confirmation of the disease Monday from the lab and that it is the fourth time since 2022 that the disease was detected at a commercial facility in Michigan.

Department spokesperson Jennifer Holton said Tuesday that state law prohibits the department from disclosing the type of poultry at the facility. The facility has been placed under quarantine and the department does not anticipate any disruptions to supply chains across the state, Holton said.

Dairy cows in Texas and Kansas were reported to be infected with bird flu last week — and federal agriculture officials later confirmed infections in a Michigan dairy herd that had recently received cows from Texas. A dairy herd in Idaho has been added to the list after federal agriculture officials confirmed the detection of bird flu in them, according to a Tuesday press release from the USDA.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Ken Miller

Published Apr 02, 2024 • 2 minute read

The largest producer of fresh eggs in the U.S. said Tuesday it had temporarily halted production at a Texas plant after bird flu was found in chickens, and officials said the virus had also been detected at a poultry facility in Michigan.

Ridgeland, Mississippi-based Cal-Maine Foods, Inc. said in a statement that approximately 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets, about 3.6% of its total flock, were destroyed after the infection, avian influenza, was found at a facility in Parmer County, Texas.

The plant is on the Texas-New Mexico border in the Texas Panhandle about 85 miles (137 kilometers) southwest of Amarillo and about 370 miles (595 kilometers) northwest of Dallas. Cal-Maine said it sells most of its eggs in the Southwestern, Southeastern, Midwestern and mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.

“The Company continues to work closely with federal, state and local government officials and focused industry groups to mitigate the risk of future outbreaks and effectively manage the response,” the statement said.

“Cal-Maine Foods is working to secure production from other facilities to minimize disruption to its customers,” the statement said.

The company said there is no known bird flu risk associated with eggs that are currently in the market and no eggs have been recalled.

Eggs that are properly handled and cooked are safe to eat, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The announcement by Cal-Maine comes a day after state health officials said a person had been diagnosed with bird flu after being in contact with cows presumed to be infected, and that the risk to the public remains low. The human case in Texas marks the first known instance globally of a person catching this version of bird flu from a mammal, federal health officials said.

In Michigan, Michigan State University’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory has detected bird flu in a commercial poultry facility in Ionia County, according to the Michigan’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

The county is about 100 miles (161 kilometers) northwest of Detroit.

The department said it received confirmation of the disease Monday from the lab and that it is the fourth time since 2022 that the disease was detected at a commercial facility in Michigan.

Department spokesperson Jennifer Holton said Tuesday that state law prohibits the department from disclosing the type of poultry at the facility. The facility has been placed under quarantine and the department does not anticipate any disruptions to supply chains across the state, Holton said.

Dairy cows in Texas and Kansas were reported to be infected with bird flu last week — and federal agriculture officials later confirmed infections in a Michigan dairy herd that had recently received cows from Texas. A dairy herd in Idaho has been added to the list after federal agriculture officials confirmed the detection of bird flu in them, according to a Tuesday press release from the USDA.

Largest fresh egg producer in U.S. has found bird flu in chickens at Texas, Michigan plants

Largest producer of fresh eggs in the U.S. said it had temporarily halted production at a Texas plant after bird flu was found in chickens

Dinosaur Disease. It's gotta be an ancient virus.Largest fresh egg producer in U.S. has found bird flu in chickens at Texas, Michigan plants

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Ken Miller

Published Apr 02, 2024 • 2 minute read

The largest producer of fresh eggs in the U.S. said Tuesday it had temporarily halted production at a Texas plant after bird flu was found in chickens, and officials said the virus had also been detected at a poultry facility in Michigan.

Ridgeland, Mississippi-based Cal-Maine Foods, Inc. said in a statement that approximately 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets, about 3.6% of its total flock, were destroyed after the infection, avian influenza, was found at a facility in Parmer County, Texas.

The plant is on the Texas-New Mexico border in the Texas Panhandle about 85 miles (137 kilometers) southwest of Amarillo and about 370 miles (595 kilometers) northwest of Dallas. Cal-Maine said it sells most of its eggs in the Southwestern, Southeastern, Midwestern and mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.

“The Company continues to work closely with federal, state and local government officials and focused industry groups to mitigate the risk of future outbreaks and effectively manage the response,” the statement said.

“Cal-Maine Foods is working to secure production from other facilities to minimize disruption to its customers,” the statement said.

The company said there is no known bird flu risk associated with eggs that are currently in the market and no eggs have been recalled.

Eggs that are properly handled and cooked are safe to eat, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The announcement by Cal-Maine comes a day after state health officials said a person had been diagnosed with bird flu after being in contact with cows presumed to be infected, and that the risk to the public remains low. The human case in Texas marks the first known instance globally of a person catching this version of bird flu from a mammal, federal health officials said.

In Michigan, Michigan State University’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory has detected bird flu in a commercial poultry facility in Ionia County, according to the Michigan’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

The county is about 100 miles (161 kilometers) northwest of Detroit.

The department said it received confirmation of the disease Monday from the lab and that it is the fourth time since 2022 that the disease was detected at a commercial facility in Michigan.

Department spokesperson Jennifer Holton said Tuesday that state law prohibits the department from disclosing the type of poultry at the facility. The facility has been placed under quarantine and the department does not anticipate any disruptions to supply chains across the state, Holton said.

Dairy cows in Texas and Kansas were reported to be infected with bird flu last week — and federal agriculture officials later confirmed infections in a Michigan dairy herd that had recently received cows from Texas. A dairy herd in Idaho has been added to the list after federal agriculture officials confirmed the detection of bird flu in them, according to a Tuesday press release from the USDA.

Largest fresh egg producer in U.S. has found bird flu in chickens at Texas, Michigan plants

Largest producer of fresh eggs in the U.S. said it had temporarily halted production at a Texas plant after bird flu was found in chickenstorontosun.com

American contracts bird flu after exposure to virus spreading in cows

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Michelle Fay Cortez

Published Apr 03, 2024 • 1 minute read

A person in Texas contracted bird flu, most likely after being exposed to infected dairy cows, public health officials said, as an emerging outbreak among the animals spreads in the country.

The risk to the general population remains low, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. It is the second human case of bird flu, formally known as highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza, in the U.S. since 2022 when infections started gaining speed in wild and domesticated birds and other mammals.

Article content

The patient, who had no symptoms apart from red eyes suggestive of conjunctivitis, is receiving antiviral drugs and recovering, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The outbreak among dairy herds is relatively recent, with early reports of infected cows from Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico and Idaho. Unlike with chickens and other poultry flocks that are generally culled to prevent the spread of the virus, the U.S. Department of Agriculture isn’t recommending the destruction of infected cows “at this stage.”

The situation is “rapidly evolving,” the USDA said. The CDC is working with state health departments to monitor people and groups that may be at risk.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News

Michelle Fay Cortez

Published Apr 03, 2024 • 1 minute read

A person in Texas contracted bird flu, most likely after being exposed to infected dairy cows, public health officials said, as an emerging outbreak among the animals spreads in the country.

The risk to the general population remains low, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. It is the second human case of bird flu, formally known as highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza, in the U.S. since 2022 when infections started gaining speed in wild and domesticated birds and other mammals.

Article content

The patient, who had no symptoms apart from red eyes suggestive of conjunctivitis, is receiving antiviral drugs and recovering, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The outbreak among dairy herds is relatively recent, with early reports of infected cows from Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico and Idaho. Unlike with chickens and other poultry flocks that are generally culled to prevent the spread of the virus, the U.S. Department of Agriculture isn’t recommending the destruction of infected cows “at this stage.”

The situation is “rapidly evolving,” the USDA said. The CDC is working with state health departments to monitor people and groups that may be at risk.

American contracts bird flu after exposure to virus spreading in cows

A person in Texas contracted bird flu, most likely after being exposed to infected dairy cows, public health officials said.

Man who received pig kidney transplant leaves hospital, feels great

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Jennifer Hassan, The Washington Post

Published Apr 04, 2024 • 3 minute read

Pig Kidney Transplant

A pig kidney sits on ice, awaiting transplantation into a living human at Massachusetts General Hospital, Saturday, March 16, 2024, in Boston, Mass. PHOTO BY MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL VIA AP

Just over two weeks after doctors placed a genetically edited kidney from a pig inside Richard Slayman, the 62-year-old is recovering at home and relishing “one of the happiest moments” of his life, according to a statement from the hospital that carried out the landmark four-hour surgery.

On March 16, Slayman became the first living person to receive such a transplant, according to doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a statement Wednesday, the hospital confirmed that Slayman had been discharged and was “recovering well.” The facility has credited “years of research, preclinical studies and collaboration” for the successful surgery.

“This moment – leaving the hospital today with one of the cleanest bills of health I’ve had in a long time – is one I wished would come for many years,” Slayman said in a discharge statement released by the hospital. “Now, it’s a reality and one of the happiest moments of my life.”

Slayman, who works for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, battled kidney disease for more than a decade. He had gone on dialysis and survived a human kidney transplant in 2018 but had since grown desperately ill and was near despair, The Washington Post reported last month.

As doctors planned the milestone surgery, they were required to seek approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which allowed the surgery under its “compassionate use” rules. The approval is granted in cases where a patient has a “serious or immediately life-threatening disease or condition” and there are no alternative treatments, according to the FDA.

Human and pig kidneys are of similar size. To reduce the risk of Slayman’s immune system attacking the transplanted pig’s organ, researchers needed to make 69 different edits to the pig’s genetic code.

For the more than 550,000 kidney patients in the United States receiving dialysis, Slayman’s story may offer a glimmer of hope. Leonardo V. Riella, medical director for kidney transplantation at Massachusetts General, has said he hopes that, as this science advances, dialysis will one day become obsolete.

Slayman said in his statement he was “excited to resume spending time” with his loved ones, “free from the burden of dialysis that has affected my quality of life for many years.”

As of February 2023, 88,658 people were on the waiting list for a kidney transplant in the United States, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The institute notes that White people were more likely to receive a transplant within five years, compared to Black, Hispanic, and Asian people. Experts hope medical advances, including using pig kidneys, can help address this inequity, and address the gap between those waiting for transplants and the short supply of human organs available.

New technologies have been credited for recent advances in the field. They include CRISPR, the gene-editing tool recognized in 2020 with a Nobel Prize in chemistry, which can modify organs to make them less foreign to a recipient, reducing the chance of rejection.

Some scientists have also transplanted organs from animals into donated bodies, as part of their research into Xenotransplantation – the process of implanting organs from one species into another. They hope their findings will result in the FDA one day allowing formal Xenotransplant studies, the Associated Press reported.

In recent years, two patients have died after receiving organ transplants from animals.

In 2022, the first patient in the world to receive a genetically modified pig’s heart died around two months after the procedure, according to officials at the University of Maryland Medical Center. The patient, David Bennett Sr., suffered multiple complications, and traces of a virus that infects pigs were also found in his new heart, The Post reported.

In 2023, another patient died six weeks after receiving a pig heart transplant. Before the surgery, Lawrence Faucette was dying of heart failure and was deemed ineligible for a human heart transplant due to his advanced medical conditions. The pig transplant procedure was his last chance at life.

While Faucette initially showed “significant” signs of progress, his new heart began to show “signs of rejection” in the weeks that followed, officials at the University of Maryland School of Medicine said.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Jennifer Hassan, The Washington Post

Published Apr 04, 2024 • 3 minute read

Pig Kidney Transplant

A pig kidney sits on ice, awaiting transplantation into a living human at Massachusetts General Hospital, Saturday, March 16, 2024, in Boston, Mass. PHOTO BY MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL VIA AP

Just over two weeks after doctors placed a genetically edited kidney from a pig inside Richard Slayman, the 62-year-old is recovering at home and relishing “one of the happiest moments” of his life, according to a statement from the hospital that carried out the landmark four-hour surgery.

On March 16, Slayman became the first living person to receive such a transplant, according to doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a statement Wednesday, the hospital confirmed that Slayman had been discharged and was “recovering well.” The facility has credited “years of research, preclinical studies and collaboration” for the successful surgery.

“This moment – leaving the hospital today with one of the cleanest bills of health I’ve had in a long time – is one I wished would come for many years,” Slayman said in a discharge statement released by the hospital. “Now, it’s a reality and one of the happiest moments of my life.”

Slayman, who works for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, battled kidney disease for more than a decade. He had gone on dialysis and survived a human kidney transplant in 2018 but had since grown desperately ill and was near despair, The Washington Post reported last month.

As doctors planned the milestone surgery, they were required to seek approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which allowed the surgery under its “compassionate use” rules. The approval is granted in cases where a patient has a “serious or immediately life-threatening disease or condition” and there are no alternative treatments, according to the FDA.

Human and pig kidneys are of similar size. To reduce the risk of Slayman’s immune system attacking the transplanted pig’s organ, researchers needed to make 69 different edits to the pig’s genetic code.

For the more than 550,000 kidney patients in the United States receiving dialysis, Slayman’s story may offer a glimmer of hope. Leonardo V. Riella, medical director for kidney transplantation at Massachusetts General, has said he hopes that, as this science advances, dialysis will one day become obsolete.

Slayman said in his statement he was “excited to resume spending time” with his loved ones, “free from the burden of dialysis that has affected my quality of life for many years.”

As of February 2023, 88,658 people were on the waiting list for a kidney transplant in the United States, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The institute notes that White people were more likely to receive a transplant within five years, compared to Black, Hispanic, and Asian people. Experts hope medical advances, including using pig kidneys, can help address this inequity, and address the gap between those waiting for transplants and the short supply of human organs available.

New technologies have been credited for recent advances in the field. They include CRISPR, the gene-editing tool recognized in 2020 with a Nobel Prize in chemistry, which can modify organs to make them less foreign to a recipient, reducing the chance of rejection.

Some scientists have also transplanted organs from animals into donated bodies, as part of their research into Xenotransplantation – the process of implanting organs from one species into another. They hope their findings will result in the FDA one day allowing formal Xenotransplant studies, the Associated Press reported.

In recent years, two patients have died after receiving organ transplants from animals.

In 2022, the first patient in the world to receive a genetically modified pig’s heart died around two months after the procedure, according to officials at the University of Maryland Medical Center. The patient, David Bennett Sr., suffered multiple complications, and traces of a virus that infects pigs were also found in his new heart, The Post reported.

In 2023, another patient died six weeks after receiving a pig heart transplant. Before the surgery, Lawrence Faucette was dying of heart failure and was deemed ineligible for a human heart transplant due to his advanced medical conditions. The pig transplant procedure was his last chance at life.

While Faucette initially showed “significant” signs of progress, his new heart began to show “signs of rejection” in the weeks that followed, officials at the University of Maryland School of Medicine said.

Man who received pig kidney transplant leaves hospital, feels great

Slayman became the first living person to receive such a transplant, according to doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Norfolk Southern agrees to pay $600M in settlement related to train derailment in eastern Ohio

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Josh Funk

Published Apr 09, 2024 • 2 minute read

Train-Derailment-Ohio

Debris from a Norfolk Southern freight train lies scattered and burning along the tracks on Feb. 4, 2023, the day after it derailed in East Palestine, Ohio.

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement related to a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio.

The company said Tuesday that the agreement, if approved by the court, will resolve all class action claims within a 20-mile radius from the derailment and, for those residents who choose to participate, personal injury claims within a 10-mile radius from the derailment.

Norfolk Southern added that individuals and businesses will be able to use compensation from the settlement in any manner they see fit to address potential adverse impacts from the derailment, which could include healthcare needs, property restoration and compensation for any net business loss. Individuals within 10-miles of the derailment may, at their discretion, choose to receive additional compensation for any past, current, or future personal injury from the derailment.

The company said that the settlement doesn’t include or constitute any admission of liability, wrongdoing, or fault.

The settlement is expected to be submitted for preliminary approval to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio later in April 2024. Payments to class members under the settlement could begin by the end of the year, subject to final court approval.

Norfolk Southern has already spent more than $1.1 billion on its response to the derailment, including more than $104 million in direct aid to East Palestine and its residents. Partly because Norfolk Southern is paying for the cleanup, President Joe Biden has never declared a disaster in East Palestine, which is a sore point for many residents. The railroad has promised to create a fund to help pay for the long-term health needs of the community, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Last week federal officials said that the aftermath of the train derailment doesn’t qualify as a public health emergency because widespread health problems and ongoing chemical exposures haven’t been documented.

The Environmental Protection Agency never approved that designation after the February 2023 Norfolk Southern derailment even though the disaster forced the evacuation of half the town of East Palestine and generated many fears about potential long-term health consequences of the chemicals that spilled and burned. The contamination concerns were exacerbated by the decision to blow open five tank cars filled with vinyl chloride and burn that toxic chemical three days after the derailment.

The head of the National Transportation Safety Board said recently that her agency’s investigation showed that the vent and burn of the vinyl chloride was unnecessary because the company that produced that chemical was sure no dangerous chemical reaction was happening inside the tank cars. But the officials who made the decision have said they were never told that.

The NTSB’s full investigation into the cause of the derailment won’t be complete until June, though that agency has said that an overheating wheel bearing on one of the railcars that wasn’t detected in time by a trackside sensor likely caused the crash.

The EPA has said the cleanup in East Palestine is expected to be complete sometime later this year.

Shares of Norfolk Southern Corp., based in Atlanta, fell about 1% before the opening bell Tuesday.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Josh Funk

Published Apr 09, 2024 • 2 minute read

Train-Derailment-Ohio

Debris from a Norfolk Southern freight train lies scattered and burning along the tracks on Feb. 4, 2023, the day after it derailed in East Palestine, Ohio.

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement related to a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio.

The company said Tuesday that the agreement, if approved by the court, will resolve all class action claims within a 20-mile radius from the derailment and, for those residents who choose to participate, personal injury claims within a 10-mile radius from the derailment.

Norfolk Southern added that individuals and businesses will be able to use compensation from the settlement in any manner they see fit to address potential adverse impacts from the derailment, which could include healthcare needs, property restoration and compensation for any net business loss. Individuals within 10-miles of the derailment may, at their discretion, choose to receive additional compensation for any past, current, or future personal injury from the derailment.

The company said that the settlement doesn’t include or constitute any admission of liability, wrongdoing, or fault.

The settlement is expected to be submitted for preliminary approval to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio later in April 2024. Payments to class members under the settlement could begin by the end of the year, subject to final court approval.

Norfolk Southern has already spent more than $1.1 billion on its response to the derailment, including more than $104 million in direct aid to East Palestine and its residents. Partly because Norfolk Southern is paying for the cleanup, President Joe Biden has never declared a disaster in East Palestine, which is a sore point for many residents. The railroad has promised to create a fund to help pay for the long-term health needs of the community, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Last week federal officials said that the aftermath of the train derailment doesn’t qualify as a public health emergency because widespread health problems and ongoing chemical exposures haven’t been documented.

The Environmental Protection Agency never approved that designation after the February 2023 Norfolk Southern derailment even though the disaster forced the evacuation of half the town of East Palestine and generated many fears about potential long-term health consequences of the chemicals that spilled and burned. The contamination concerns were exacerbated by the decision to blow open five tank cars filled with vinyl chloride and burn that toxic chemical three days after the derailment.

The head of the National Transportation Safety Board said recently that her agency’s investigation showed that the vent and burn of the vinyl chloride was unnecessary because the company that produced that chemical was sure no dangerous chemical reaction was happening inside the tank cars. But the officials who made the decision have said they were never told that.

The NTSB’s full investigation into the cause of the derailment won’t be complete until June, though that agency has said that an overheating wheel bearing on one of the railcars that wasn’t detected in time by a trackside sensor likely caused the crash.

The EPA has said the cleanup in East Palestine is expected to be complete sometime later this year.

Shares of Norfolk Southern Corp., based in Atlanta, fell about 1% before the opening bell Tuesday.

Norfolk Southern agrees to pay $600M in settlement related to train derailment in eastern Ohio

The company said that the settlement doesn't include or constitute any admission of liability, wrongdoing, or fault.

the place is called palestine thats why no one is doing shit to help them.Norfolk Southern agrees to pay $600M in settlement related to train derailment in eastern Ohio

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Josh Funk

Published Apr 09, 2024 • 2 minute read

Train-Derailment-Ohio

Debris from a Norfolk Southern freight train lies scattered and burning along the tracks on Feb. 4, 2023, the day after it derailed in East Palestine, Ohio.

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement related to a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio.

The company said Tuesday that the agreement, if approved by the court, will resolve all class action claims within a 20-mile radius from the derailment and, for those residents who choose to participate, personal injury claims within a 10-mile radius from the derailment.

Norfolk Southern added that individuals and businesses will be able to use compensation from the settlement in any manner they see fit to address potential adverse impacts from the derailment, which could include healthcare needs, property restoration and compensation for any net business loss. Individuals within 10-miles of the derailment may, at their discretion, choose to receive additional compensation for any past, current, or future personal injury from the derailment.

The company said that the settlement doesn’t include or constitute any admission of liability, wrongdoing, or fault.

The settlement is expected to be submitted for preliminary approval to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio later in April 2024. Payments to class members under the settlement could begin by the end of the year, subject to final court approval.

Norfolk Southern has already spent more than $1.1 billion on its response to the derailment, including more than $104 million in direct aid to East Palestine and its residents. Partly because Norfolk Southern is paying for the cleanup, President Joe Biden has never declared a disaster in East Palestine, which is a sore point for many residents. The railroad has promised to create a fund to help pay for the long-term health needs of the community, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Last week federal officials said that the aftermath of the train derailment doesn’t qualify as a public health emergency because widespread health problems and ongoing chemical exposures haven’t been documented.

The Environmental Protection Agency never approved that designation after the February 2023 Norfolk Southern derailment even though the disaster forced the evacuation of half the town of East Palestine and generated many fears about potential long-term health consequences of the chemicals that spilled and burned. The contamination concerns were exacerbated by the decision to blow open five tank cars filled with vinyl chloride and burn that toxic chemical three days after the derailment.

The head of the National Transportation Safety Board said recently that her agency’s investigation showed that the vent and burn of the vinyl chloride was unnecessary because the company that produced that chemical was sure no dangerous chemical reaction was happening inside the tank cars. But the officials who made the decision have said they were never told that.

The NTSB’s full investigation into the cause of the derailment won’t be complete until June, though that agency has said that an overheating wheel bearing on one of the railcars that wasn’t detected in time by a trackside sensor likely caused the crash.

The EPA has said the cleanup in East Palestine is expected to be complete sometime later this year.

Shares of Norfolk Southern Corp., based in Atlanta, fell about 1% before the opening bell Tuesday.

Norfolk Southern agrees to pay $600M in settlement related to train derailment in eastern Ohio

The company said that the settlement doesn't include or constitute any admission of liability, wrongdoing, or fault.torontosun.com

Tsunami alert after a volcano in Indonesia has several big eruptions and thousands are told to leave

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Edna Tarigan

Published Apr 17, 2024 • 1 minute read

Indonesia-Volcano-Eruptions

In this photo released by Sitaro Regional Disaster Management Agency (BPBD Sitaro), hot molten lava glows at the crater of Mount Ruang as it erupts in Sanguine Islands, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Indonesian authorities issued a tsunami alert Wednesday after eruptions at Ruang mountain sent ash thousands of feet high. Officials ordered more than 11,000 people to leave the area. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Article content

JAKARTA, Indonesia (AP) — Indonesian authorities issued a tsunami alert Wednesday after eruptions at Ruang mountain sent ash thousands of feet high. Officials ordered more than 11,000 people to leave the area.

The volcano on the northern side of Sulawesi island had at least five large eruptions in the past 24 hours, Indonesia’s Center for Volcanology and Geological Disaster Mitigation said. Authorities raised their volcano alert to its highest level.

At least 800 residents left the area earlier Wednesday.

Indonesia, an archipelago of 270 million people, has 120 active volcanoes. It is prone to volcanic activity because it sits along the “Ring of Fire,” a horseshoe-shaped series of seismic fault lines around the Pacific Ocean.

Authorities urged tourists and others to stay at least 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) from the 725-meter (2,378 foot) Ruang volcano.

Officials worry that part of the volcano could collapse into the sea and cause a tsunami as in a 1871 eruption there.

Tagulandang island to the volcano’s northeast is again at risk, and its residents are among those being told to evacuate.

Indonesia’s National Disaster Mitigation Agency said residents will be relocated to Manado, the nearest city, on Sulawesi island, a journey of six hours by boat.

In 2018, the eruption of Indonesia’s Anak Krakatau volcano caused a tsunami along the coasts of Sumatra and Java after parts of the mountain fell into the ocean, killing 430 people.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Edna Tarigan

Published Apr 17, 2024 • 1 minute read

Indonesia-Volcano-Eruptions

In this photo released by Sitaro Regional Disaster Management Agency (BPBD Sitaro), hot molten lava glows at the crater of Mount Ruang as it erupts in Sanguine Islands, Indonesia, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Indonesian authorities issued a tsunami alert Wednesday after eruptions at Ruang mountain sent ash thousands of feet high. Officials ordered more than 11,000 people to leave the area. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Article content

JAKARTA, Indonesia (AP) — Indonesian authorities issued a tsunami alert Wednesday after eruptions at Ruang mountain sent ash thousands of feet high. Officials ordered more than 11,000 people to leave the area.

The volcano on the northern side of Sulawesi island had at least five large eruptions in the past 24 hours, Indonesia’s Center for Volcanology and Geological Disaster Mitigation said. Authorities raised their volcano alert to its highest level.

At least 800 residents left the area earlier Wednesday.

Indonesia, an archipelago of 270 million people, has 120 active volcanoes. It is prone to volcanic activity because it sits along the “Ring of Fire,” a horseshoe-shaped series of seismic fault lines around the Pacific Ocean.

Authorities urged tourists and others to stay at least 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) from the 725-meter (2,378 foot) Ruang volcano.

Officials worry that part of the volcano could collapse into the sea and cause a tsunami as in a 1871 eruption there.

Tagulandang island to the volcano’s northeast is again at risk, and its residents are among those being told to evacuate.

Indonesia’s National Disaster Mitigation Agency said residents will be relocated to Manado, the nearest city, on Sulawesi island, a journey of six hours by boat.

In 2018, the eruption of Indonesia’s Anak Krakatau volcano caused a tsunami along the coasts of Sumatra and Java after parts of the mountain fell into the ocean, killing 430 people.

Tsunami alert after a volcano in Indonesia has several big eruptions and thousands are told to leave

At least 800 residents left the area earlier Wednesday.

Cap on plastic production remains contentious as Ottawa set to host treaty talks

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Mia Rabson

Published Apr 21, 2024 • 5 minute read

Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years.

Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years. PHOTO BY PAUL CHIASSON /THE CANADIAN PRESS

OTTAWA — Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years.

Ottawa is hosting the fourth of five rounds of negotiations, with the aim of finalizing a deal by the end of the year.

The proliferation of plastics has been profound, as it is a preferred material largely for its affordability and longevity. But that also means it never goes away, and the impact on nature and growing concerns about human health are leading a push to get rid of plastic waste and eliminate the most problematic chemicals used to make it.

Canada’s environment minister, Steven Guilbeault, played a crucial role in getting the plastic treaty talks underway in 2022 when he helped push a resolution at the United Nations Environment Assembly in Kenya. He remains firm that a strong treaty is needed.

“We want to move as rapidly as possible to eliminate plastic pollution,” he said in an interview with The Canadian Press. “I mean, the collective goal we’ve set for ourselves is to do it by 2040, but I think both from an environmental and a health perspective, the sooner the better.”

But Guilbeault is still reluctant to take a definitive position on the elephant in the negotiating room: a cap on plastic production.

“We want an ambitious treaty,” he said.

“I don’t think right now is the time to start … getting bogged down on certain things and say, ‘OK, well, this is it.’ Let’s have the conversation and see where we land.”

For many environmental and health organizations observing the talks, the only way to solve the plastic crisis is to cut back on the amount produced in the first place.

But that’s a no-go zone for the chemical and plastic production industries, whose members argue alternatives to plastic are often more expensive, more energy intensive and heavier.

Karen Wirsig, senior program manager for plastics at advocacy organization Environmental Defence, said plastic production will double by 2050 if left unchecked. Plastic waste could triple by 2060, she added.

“Plastic pollution is a global crisis that intensifies every day when we let plastic production and use go unchecked,” she said.

“The Earth and our health cannot afford business as usual.”

The Organization for Economic Co-operation says global plastic production grew from 234 million tonnes in 2000 to 460 million tonnes in 2019, while plastic waste grew from 156 million tonnes to 353 million tonnes.

Globally about half of that waste ends up in landfills, one-fifth is incinerated, sometimes to create electricity, and almost one-tenth is recycled. More than one-fifth is “mismanaged,” meaning it ends up in places it is not supposed to be.

The mismanagement issue is far worse in developing economies, where waste management programs are limited if they exist at all. In some parts of Africa, the OECD said almost two-thirds of plastic waste is mismanaged, and in much of Asia almost half. That compares with less than one-tenth across the world’s richest countries.

Adding to that problem is that rich countries continue to export their garbage overseas despite international rules in place to prevent the practice. Last fall a Canadian Press investigation in partnership with Lighthouse Reports and journalists in Myanmar, Thailand and Europe found evidence of Canadian plastic food wrappers and plumbing parts in trash heaps encircling homes and gardens in a Myanmar town.

In Canada, the OECD reported, more than 80 per cent of plastic waste is landfilled, and only six per cent recycled. Seven per cent is mismanaged.

The evolving treaty has several areas of focus, including discussions on a cap on production, reducing the types of products most commonly found in nature, and what are known as chemicals of concern.

A UN report prepared ahead of the second round of treaty talks in Paris last June said more than 13,000 chemicals are used to make plastics, and 10 groups of those chemicals are highly toxic and likely to leech out of their products. That includes flame retardants, ultraviolet stabilizers and additives used to make plastics harder, waterproof or stain resistant.

Dr. Lyndia Dernis, a Montreal anesthesiologist and member of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, said most plastic additives are endocrine disrupters, which cause everything from diabetes and obesity to high blood pressure, infertility, cancer and immunologic disorders.

Plastic is extremely common in medicine. When she starts an intravenous for a pregnant patient, for instance, she said that material contains phthalates, “a very well studied endocrine disruptor.”

“Early in pregnancy the baby girl’s reproductive system is in place, including all the eggs for the rest of her life. This means that when I start an intravenous, I’m exposing three generations at once: the pregnant mom, her future baby girl, and the babies of that baby to be,” she said.

Greenpeace and other environmental groups are calling for plastic production to be cut 75 per cent from 2019 levels by 2040. Recycling, they argue, is a myth that doesn’t really happen. Most of what Canadians toss in their blue boxes still ends up in the landfill.

Isabelle Des Chenes, vice-president of policy for the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada, said society can’t ban or cap its way out of plastic waste.

For Des Chenes, the key component to the treaty is to create a “circular economy” where companies design products to be reused and recycled, rather than thrown away.

That includes investments in equipment to break plastics back down into their original compounds to be used again, as well as standardizing designs to make recycling possible, she said.

Des Chenes said if you just look at potato chip bags, which are made of layers of different plastic polymers, those layers differ depending on the brand. It is easier to recycle those bags if there is consistency.

Guilbeault has promised regulations in Canada to require both minimum amounts of recycled content in plastics and consistency in design. Both will increase a market for recycling, which is very limited in Canada. Updates on those promises could be expected during the treaty talks, he implied.

Some of Canada’s domestic efforts are on pause after the Federal Court ruled last fall that a government decision to designate all plastics as “toxic” was too broad. That designation is what Canada is using to ban the production and use of some single-use plastics like straws, grocery bags and takeout containers.

Canada is appealing that decision and Guilbeault said the case won’t have any influence on federal positions during treaty talks.

November treaty talks in Kenya saw the deal’s draft text balloon from 35 pages to more than 70. It currently contains a lot of repetition, with multiple options on line items reflecting varying viewpoints.

Guilbeault said he’d like to get that text “70 per cent clean” by the end of the Ottawa round, leaving the most difficult issues to be handled in side talks over the summer and then in the final discussions in Korea in the fall.

The treaty talks in Ottawa begin Tuesday and run for seven days.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Canadian Press

Canadian Press

Mia Rabson

Published Apr 21, 2024 • 5 minute read

Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years.

Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years. PHOTO BY PAUL CHIASSON /THE CANADIAN PRESS

OTTAWA — Negotiators from 176 countries will gather in downtown Ottawa this week for the fourth round of talks to create a global treaty to eliminate plastic waste in less than 20 years.

Ottawa is hosting the fourth of five rounds of negotiations, with the aim of finalizing a deal by the end of the year.

The proliferation of plastics has been profound, as it is a preferred material largely for its affordability and longevity. But that also means it never goes away, and the impact on nature and growing concerns about human health are leading a push to get rid of plastic waste and eliminate the most problematic chemicals used to make it.

Canada’s environment minister, Steven Guilbeault, played a crucial role in getting the plastic treaty talks underway in 2022 when he helped push a resolution at the United Nations Environment Assembly in Kenya. He remains firm that a strong treaty is needed.

“We want to move as rapidly as possible to eliminate plastic pollution,” he said in an interview with The Canadian Press. “I mean, the collective goal we’ve set for ourselves is to do it by 2040, but I think both from an environmental and a health perspective, the sooner the better.”

But Guilbeault is still reluctant to take a definitive position on the elephant in the negotiating room: a cap on plastic production.

“We want an ambitious treaty,” he said.

“I don’t think right now is the time to start … getting bogged down on certain things and say, ‘OK, well, this is it.’ Let’s have the conversation and see where we land.”

For many environmental and health organizations observing the talks, the only way to solve the plastic crisis is to cut back on the amount produced in the first place.

But that’s a no-go zone for the chemical and plastic production industries, whose members argue alternatives to plastic are often more expensive, more energy intensive and heavier.

Karen Wirsig, senior program manager for plastics at advocacy organization Environmental Defence, said plastic production will double by 2050 if left unchecked. Plastic waste could triple by 2060, she added.

“Plastic pollution is a global crisis that intensifies every day when we let plastic production and use go unchecked,” she said.

“The Earth and our health cannot afford business as usual.”

The Organization for Economic Co-operation says global plastic production grew from 234 million tonnes in 2000 to 460 million tonnes in 2019, while plastic waste grew from 156 million tonnes to 353 million tonnes.

Globally about half of that waste ends up in landfills, one-fifth is incinerated, sometimes to create electricity, and almost one-tenth is recycled. More than one-fifth is “mismanaged,” meaning it ends up in places it is not supposed to be.

The mismanagement issue is far worse in developing economies, where waste management programs are limited if they exist at all. In some parts of Africa, the OECD said almost two-thirds of plastic waste is mismanaged, and in much of Asia almost half. That compares with less than one-tenth across the world’s richest countries.

Adding to that problem is that rich countries continue to export their garbage overseas despite international rules in place to prevent the practice. Last fall a Canadian Press investigation in partnership with Lighthouse Reports and journalists in Myanmar, Thailand and Europe found evidence of Canadian plastic food wrappers and plumbing parts in trash heaps encircling homes and gardens in a Myanmar town.

In Canada, the OECD reported, more than 80 per cent of plastic waste is landfilled, and only six per cent recycled. Seven per cent is mismanaged.

The evolving treaty has several areas of focus, including discussions on a cap on production, reducing the types of products most commonly found in nature, and what are known as chemicals of concern.

A UN report prepared ahead of the second round of treaty talks in Paris last June said more than 13,000 chemicals are used to make plastics, and 10 groups of those chemicals are highly toxic and likely to leech out of their products. That includes flame retardants, ultraviolet stabilizers and additives used to make plastics harder, waterproof or stain resistant.

Dr. Lyndia Dernis, a Montreal anesthesiologist and member of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, said most plastic additives are endocrine disrupters, which cause everything from diabetes and obesity to high blood pressure, infertility, cancer and immunologic disorders.

Plastic is extremely common in medicine. When she starts an intravenous for a pregnant patient, for instance, she said that material contains phthalates, “a very well studied endocrine disruptor.”

“Early in pregnancy the baby girl’s reproductive system is in place, including all the eggs for the rest of her life. This means that when I start an intravenous, I’m exposing three generations at once: the pregnant mom, her future baby girl, and the babies of that baby to be,” she said.

Greenpeace and other environmental groups are calling for plastic production to be cut 75 per cent from 2019 levels by 2040. Recycling, they argue, is a myth that doesn’t really happen. Most of what Canadians toss in their blue boxes still ends up in the landfill.

Isabelle Des Chenes, vice-president of policy for the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada, said society can’t ban or cap its way out of plastic waste.

For Des Chenes, the key component to the treaty is to create a “circular economy” where companies design products to be reused and recycled, rather than thrown away.

That includes investments in equipment to break plastics back down into their original compounds to be used again, as well as standardizing designs to make recycling possible, she said.

Des Chenes said if you just look at potato chip bags, which are made of layers of different plastic polymers, those layers differ depending on the brand. It is easier to recycle those bags if there is consistency.

Guilbeault has promised regulations in Canada to require both minimum amounts of recycled content in plastics and consistency in design. Both will increase a market for recycling, which is very limited in Canada. Updates on those promises could be expected during the treaty talks, he implied.

Some of Canada’s domestic efforts are on pause after the Federal Court ruled last fall that a government decision to designate all plastics as “toxic” was too broad. That designation is what Canada is using to ban the production and use of some single-use plastics like straws, grocery bags and takeout containers.

Canada is appealing that decision and Guilbeault said the case won’t have any influence on federal positions during treaty talks.

November treaty talks in Kenya saw the deal’s draft text balloon from 35 pages to more than 70. It currently contains a lot of repetition, with multiple options on line items reflecting varying viewpoints.

Guilbeault said he’d like to get that text “70 per cent clean” by the end of the Ottawa round, leaving the most difficult issues to be handled in side talks over the summer and then in the final discussions in Korea in the fall.

The treaty talks in Ottawa begin Tuesday and run for seven days.

Cap on plastic production remains contentious as Ottawa set to host treaty talks

"The Earth and our health cannot afford business as usual."

Bed bugs, bats and other pests found in federal government buildings

26 Crown-owned buildings had some unwelcome visitors between Jan. 1 and March 31

Author of the article:Catherine Morrison

Published Apr 22, 2024 • Last updated 19 hours ago • 3 minute read

The C.D. Howe Building at 240 Sparks St. in Ottawa.

The C.D. Howe Building at 240 Sparks St. in Ottawa.

The federal government has solved the housing crisis for a handful of critters, with Public Services and Procurement Canada receiving 256 service calls about the potential presence of pests in buildings across the National Capital Region already this year.

A list from PSPC showed that 26 Crown-owned buildings had some unwelcome visitors between Jan. 1 and March 31.

Pests found in the buildings included mice, bed bugs, bats, ants, a skunk, raccoons and insects like silverfish, drain flies, beetles and sand ants.

“Unfortunately, pests are a nuisance commonly faced in commercial real estate, which can be concerning to building occupants,” PSPC spokesperson Alexandre Baillairgé-Charbonneau said. “The number of service calls related to pests can fluctuate depending on levels of occupancy in the building, weather, food sources and other factors.”

The most pest-friendly building in the region has been the C.D. Howe Building on Sparks Street. The presence of mice there has been confirmed 14 times this year, with the presence of insects confirmed once. Treatments included installing mouse traps, with PSPC noting in once instance that calls for mice were mainly attributed to a garage repair project that “disrupted” the mice.

Geomatics Canada Building

The Geomatics Canada Building at 615 Booth St. in Ottawa.

Several other government structures in the capital region have also been entered by mice in recent months, including the Lester B. Pearson Building A, the Exhibition Commission Office, the Sir William Logan Building and the Geomatics Canada Building.

In addition to mice, bats were discovered in offices of the Geomatics Canada Building on Booth Street three times since January; captured by pest control, they were released offsite. PSPC said bat houses had been installed on the building’s roof to “provide an alternative” for the creatures.

Baillairgé-Charbonneau said integrated pest management programs were incorporated into building operations and all reports of pests were taken “very seriously and promptly investigated.”

The spokesperson also said that, when pests were reported, an investigation was initiated and pest control professionals were hired to advise on treatment options.

“Proactive monitoring is often used to determine the effectiveness of the treatment,” Baillairgé-Charbonneau said. “Treatment plans are unique to every building and type of pest, but each report is taken very seriously by PSPC and their service providers, prompting action as quickly as possible.”

Last summer, when bed bugs and other pests were reported in buildings across the capital region, Public Service Alliance of Canada’s regional executive vice-president Alex Silas said their presence was “disappointing,” but not a new problem.

“Unfortunately, it’s become the norm to hear stories like this in federal public-service workplaces, especially in the NCR,” Silas said then, adding the issue should have been addressed while federal buildings were largely empty during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Place du Centre

The Place du Centre Office Tower at 200 Promenade du Portage in Gatineau.