American author Bill Bryson is so much of an Anglophile that he has spent most of his adult life living in Great Britain.

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1951, Bryson visited the UK in 1973, fell in love with the place and decided to stay. He fell in love with a nurse at the psychiatric hospital he worked at and the pair eventually got married. After spending a few years in Iowa, the pair returned to Britain in 1977. Bryson eventually became a newspaper journalist and the couple had children.

In 1995, the family went to live in Hanover in New Hampshire. Before moving there, Bryson took a trip around the UK and wrote of his travels in a book he published in 1996 - Notes From A Small Island. The book became a bestseller in the UK.

During this trip he insisted on using only public transport, but failed on two occasions: in Oxfordshire and on the journey to John o' Groats he had to rent a car. He also re-visits Virginia Water where he worked at the Holloway Sanatorium when he first came to Britain in 1973.

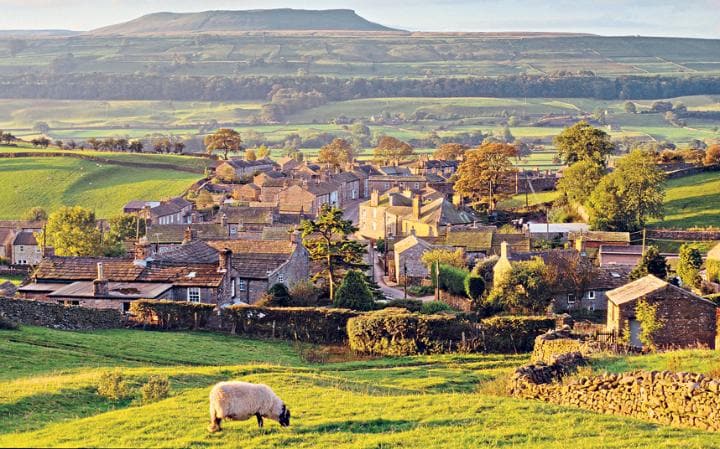

On his way, Bryson provides historical information on the places he visits, and expresses amazement at the heritage in Britain, stating that there were 445,000 listed historical buildings, 12,000 medieval churches, 1,500,000 acres (600,000 ha) of common land, 120,000 miles (190,000 km) of footpaths and public rights-of-way, 600,000 known sites of archaeological interest and that in his Yorkshire village at that time, there were more 17th century buildings than in the whole of North America.

In the end, Bryson and his family didn't stay in New Hampshire for long. In 2003 they moved back to the UK and Bryson eventually made himself a British citizen. In 2005 he was made chancellor of Durham University, and became president of the Campaign to Protect Rural England in 2007.

Apart from Notes from a Small Island, Bryson has also written books on science, the English language and other non-fiction topics, including other travel books - he has written about his travels around Australia, Europe and the Appalachian Trail.

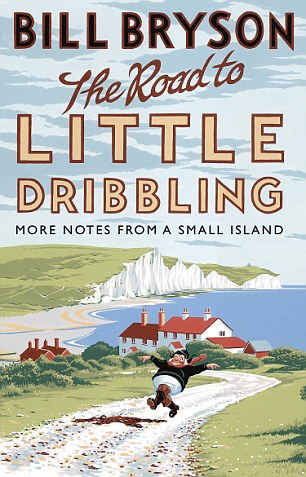

His latest book - The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes From a Small Island, the sequel to Notes From A Small Island - was published last year.

Twenty years on, here are some of the most joyous highlights from Notes From A Small Island...

The man who'll make you love Britain anew (even the bits we all moan about): Twenty years on, the most joyous highlights from BILL BRYSON'S Notes From a Small Island in a series which will lift your heart

By Bill Bryson For Daily Mail

13 August 2016

Bill Bryson: The Anglo-American author's book about his travels around the UK became a bestseller

There is a small, tattered clipping that I sometimes carry with me and pull out for purposes of private amusement. It’s a weather forecast from the Western Daily Mail and it says, in toto: ‘Outlook: Dry and warm, but cooler with some rain.’

There you have in a single pithy sentence the British weather captured to perfection: dry but rainy with some warm/cool spells. The Western Daily Mail could run that forecast every day — for all I know, it may — and scarcely ever be wrong.

To an outsider the most striking thing about the British weather is that there isn’t very much of it. All those phenomena that elsewhere give nature an edge of excitement, unpredictability and danger — tornadoes, monsoons, raging blizzards, run-for-your-life hailstorms — are almost wholly unknown in the British Isles, and this is just fine by me.

Bill Bryson has started a series on life in Britain with all of its oddities and customs

I like wearing the same type of clothing every day of the year. I appreciate not needing air conditioning or mesh screens on the windows to keep out the kind of insects and flying animals that drain your blood or eat away your face while you are sleeping. I like knowing that so long as I do not go walking up Ben Nevis in carpet slippers in February I will almost certainly never perish from the elements in this soft and gentle country.

I mention this because as I sat eating my breakfast in the dining room of the Old England Hotel in Bowness-on-Windermere, two days after leaving Morecambe, I was reading an article in The Times about an unseasonable snowstorm — a ‘blizzard’, The Times called it — that had ‘gripped’ parts of East Anglia.

According to The Times report, the storm had covered parts of the region with ‘more than 2in of snow’ and created ‘drifts up to 6in high’.

In response to this, I did something I had never done before: I pulled out my notebook and drafted a letter to the editor in which I pointed out, in a kindly, helpful way, that 2in of snow cannot possibly constitute a blizzard and that 6in of snow is not a drift.

A blizzard, I explained, is when you can’t get your front door open. Drifts are things that make you lose your car until spring. Cold weather is when you leave part of your flesh on doorknobs, mailbox handles and other metal objects.

Then I crumpled the letter up because I realised I was in danger of turning into one of the Colonel Blimp types who sat around me, eating cornflakes or porridge with their blimpish wives, and without whom hotels like the Old England would not be able to survive.

I was in Bowness because I had two days to kill until I was to be joined by two friends from London with whom I was going to spend the weekend walking. I was looking forward to that, but rather less to the prospect of another long, purposeless day in Bowness, pottering about trying to fill the empty hours till tea.

There are, I find, only so many windowsful of tea towels, Peter Rabbit dinnerware and patterned jumpers I can look at before my interest in shopping palls, and I wasn’t at all sure that I could face another day of poking about in this most challenging of resorts.

I had come to Bowness more or less by default since it is the only place inside the Lake District National Park with a railway station.

Besides, the idea of spending a couple of quiet days beside the tranquil beauty of Windermere, and wallowing in the plump comforts of a gracious (if costly) old hotel, had seemed distinctly appealing from the vantage of Morecambe Bay.

But now, with one day down and another to go, I was feeling stranded and fidgety, like someone at the end of a long period of convalescence.

Ambleside in the Lake District

At least, I reflected optimistically, the unseasonable 2in of snow that had brutally lashed East Anglia, causing chaos on the roads and forcing people to battle their way through perilous snowdrifts, some as high as their ankletops, had mercifully passed this corner of England by.

Here, the elements were benign and the world outside the dining-room window sparkled weakly under a pale wintry sun.

I decided to take the lake steamer to Ambleside. This would not only kill an hour and let me see the lake, but deliver me to a place rather more like a real town and less like a misplaced seaside resort than Bowness.

In Bowness, I had noted the day before, there are no fewer than 18 shops where you can buy jumpers and at least 12 selling Peter Rabbit stuff, but just one butcher’s.

Ambleside, though hardly unfamiliar with the possibilities for enrichment presented by hordes of passing tourists, did at least have an excellent bookshop and any number of outdoor shops, which I find hugely if inexplicably diverting — I can spend hours looking at rucksacks, kneesocks, compasses and survival rations, then go to another shop and look at precisely the same things all over again.

So it was with a certain animated keenness that I made my way to the steamer pier after breakfast.

Alas, I discovered the steamers run only in summer, which seemed shortsighted on this mild morning because even now Bowness gently teemed with trippers.

Members of the public enjoy the hot sunny weather at Goodrington in Devon

So I was forced, as a fallback, to pick my way through the scattered, shuffling throngs to the little ferry that shunts back and forth between Bowness and the old ferry house on the opposite shore. It travels only a few hundred yards, but it does at least run all year.

A modest line-up of cars was patiently idling on the ferry approach, and there were eight or ten walkers as well, all with Mustos, rucksacks and sturdy boots. One fellow was even wearing shorts — always a sign of advanced dementia in a British walker.

Walking — walking, that is, in the British sense — was something I had come into only relatively recently.

I was not yet at the point where I would wear shorts with many pockets, but I had taken to tucking my trousers into my socks (though I have yet to find anyone who can explain what benefits this confers, other than making one look serious and committed). I remember when I first came to Britain wandering into a bookstore and being surprised to find a section dedicated to ‘Walking Guides’.

This struck me as faintly comical — where I came from people did not require written instructions to achieve locomotion — but gradually I learned that there are two kinds of walking in Britain: the everyday kind that gets you to the pub and, all being well, home again, and the kind that involves stout boots, Ordnance Survey maps in plastic pouches, rucksacks with sandwiches and flasks of tea, and, in its terminal phase, the wearing of khaki shorts in inappropriate weather.

For years, I watched these walker types toiling off up cloud-hidden hills in wet and savage weather and presumed they were genuinely insane. And then my old friend John Price, who had grown up in Liverpool and spent his youth doing foolish things on sheer-faced crags in the Lakes, encouraged me to join him and a couple of his friends for an amble — that was the word he used — up Haystacks one weekend.

To an outsider the most striking thing about the British weather is that there isn’t very much of it - and that is how Bill Bryson likes it

I think it was the combination of those two untaxing-sounding words, ‘amble’ and ‘Haystacks’, and the promise of lots of drink afterwards, that lulled me from caution.

‘Are you sure it’s not too hard?’ I asked.

‘Nah, just an amble,’ John insisted.

Well, of course it was anything but an amble. We clambered for hours up vast, perpendicular slopes, over clattering scree and lumpy tussocks, round towering citadels of rock, and emerged at length into a cold, bleak, lofty nether world so remote and forbidding that even the sheep were startled to see us.

Beyond it lay even greater and remoter summits that had been invisible from the ribbon of black highway thousands of feet below,

John and his chums toyed with my will to live in the cruellest possible way; seeing me falling behind, they would lounge around on boulders, smoking and chatting and resting, but the instant I caught up with them with a view to falling at their feet, they would bound up refreshed and, with a few encouraging words, set off anew with large, manly strides, so that I had to stumble after and never got a rest.

I gasped and ached and sputtered, and realised that I had never done anything remotely this unnatural before and vowed never to attempt such folly again.

Then, just as I was about to lie down and call for a stretcher, we crested a final rise and found ourselves abruptly, magically, on top of the earth, on a platform in the sky, amid an ocean of swelling summits.

The best bits of Bill Bryson's Notes from a Small Island are being presented in a series

I had never seen anything half so beautiful before. ‘F*** me,’ I said in a moment of special eloquence and realised I was hooked. Ever since then I had come back whenever they would have me, and never complained and even started tucking my trousers in my socks. I couldn’t wait for the morrow.

The ferry docked and I shuffled on board with the others. Windermere looked serene and exceedingly fetching in the gentle sunshine.

Unusually there wasn’t a single pleasure boat disturbing its glassy calmness. To say that Windermere is popular with boaters is to flirt recklessly with understatement.

Some 14,000 powerboats — let me repeat that number: 14,000 — are registered to use the lake. On a busy summer’s day, as many as 1,600 powerboats may be out on the water at any one time, a good many of them zipping along at up to 40 miles an hour with water-skiers in tow.

This is in addition to all the thousands of other floating objects that may be out on the water and don’t need to register — dinghies, sailboats, sailboards, canoes, inflatables, li-los, various excursion steamers and the old chugging ferry I was on now — all of them searching for a boat-sized piece of water.

It is all but impossible to stand on a lakeside bank on an August Sunday watching water-skiers slicing through packed shoals of dinghies and other floating detritus and not end up with your mouth open and your hands on your head. Yet even at its worst, the Lake District remains more charming and less rapaciously commercialised than many famed beauty spots in more spacious countries.

And away from the crowds it retains pockets of sheer perfection, as I found when the ferry nosed into its landing and we tumbled off.

For a minute the landing area was a hive of activity as one group of cars got off, another got on and the eight or ten foot passengers departed in various directions.

All those phenomena that elsewhere give nature an edge of excitement, unpredictability and danger — tornadoes, monsoons, raging blizzards, run-for-your-life hailstorms — are almost wholly unknown in the British Isles

Then all was blissful silence. I followed a pretty, wooded road around the lake’s edge before turning inland and heading for Near Sawrey.

Near Sawrey is the home of Hilltop, the cottage where the inescapable Beatrix Potter drew her sweet little watercolours and contrived her soppy stories. For most of the year, it is overrun with tourists from far and wide.

Such indeed is Hilltop’s alarming popularity that the National Trust doesn’t even actively advertise it any more. Yet still the visitors come. Two coaches were disgorging chattering white-haired occupants when I arrived and the main car park was already nearly full.

I had been to Hilltop the year before, so I wandered past it and up a little-known track to a tarn on some high ground behind it. Old Mrs Potter used to come up to this tarn regularly to thrash about on it in a rowing boat — whether for healthful exercise or as a kind of flagellation I don’t know — but it was very lovely and seemingly quite forgotten. I had the distinct feeling that I was the first visitor to venture up there for years.

Across the way, a farmer was mending a stretch of fallen wall and I stood and watched him for a while from a discreet distance, because if there is one thing nearly as soothing to the spirit as mending a drystone wall it is watching someone else doing it.

I remember once, not long after we moved to the Yorkshire Dales, going for a stroll and happening across a farmer I knew slightly who was rebuilding a wall on a remote hill. It was a rotten January day full of drifting fog and rain and the thing is there wasn’t any discernible point in his rebuilding the wall.

The weather plays a major part of Britain's culture, Bill Bryson writes about

He owned the fields on either side and in any case there was a gate that stood permanently open between the two, so it wasn’t as if the wall had any real function. I watched him awhile and finally asked him why he was standing out in a cold rain rebuilding the wall.

He looked at me with that special pained look Yorkshire farmers save for onlookers and other morons and said: ‘Because it’s fallen down, of course.’

From this I learned, first of all, never to ask a Yorkshire farmer any question that can’t be answered with ‘pint of Tetley’s’ and that one of the primary reasons so much of the British landscape is so unutterably lovely and timeless is that most farmers, for whatever reason, take the trouble to keep it that way.

By 11 the next morning, when John Price and a very nice fellow named David Partridge rolled up at the hotel in Price’s car, I was waiting for them by the door. I forbade them a coffee stop in Bowness on the grounds that I could stand it no longer, and made them drive to the hotel near Bassenthwaite, where Price had booked us rooms.

There we dumped our bags, had a coffee, acquired three packed lunches from the kitchen, accoutred ourselves in stylish fell-wear and set off for Great Langdale. Now this was more like it.

Despite threatening weather and the lateness of the year, the car parks and verges along the valley were crowded. Everywhere people delved for equipment in boots or sat with car doors open pulling on warm socks and stout boots.

We dressed our feet, then fell in with a straggly army of walkers, all with rucksacks and knee-high woolly socks, and set off for a long, grassy humpback hill called the Band.

We were headed for the fabled summit of Bow Fell, at 2,960ft the sixth-highest of the Lakeland hills.

Walkers ahead of us formed well-spaced dots of slow-moving colour leading to an impossibly remote summit, lost in cloud. As ever, I was quietly astounded to find so many people had been seized with the notion that struggling up a mountainside on a damp Saturday on the winter end of October was fun.

Deckchairs and people sunbathing on the beach in Sidmouth, Devon

We climbed through the grassy lower slopes into ever-bleaker terrain, picking our way over rocks and scree, until we were up among the ragged shreds of cloud that hung above the valley floor perhaps a thousand feet below.

The views were sensational — the jagged peaks of the Langdale Pikes rising opposite and crowding against the narrow and gratifyingly remote valley, laced with tiny, stonewalled fields, and off to the west a swelling sea of hefty brown hills disappearing in mist and low cloud.

As we pressed on the weather severely worsened. The air filled with swirling particles of ice that hit the skin like razor nicks. By the time we neared Three Tarns the weather was truly menacing, with thick fog joining the jagged sleet. Ferocious gusts of wind buffeted the hillside and reduced our progress to a creeping plod.

The fog cut visibility to a few yards. Once or twice we briefly lost the path, which alarmed me as I didn’t particularly want to die up here — apart from anything else, I still had 4,700 unspent Profiles points on my Barclaycard.

Out of the murk ahead emerged what looked disconcertingly like an orange snowman. It proved on closer inspection to be a high-tech hiker’s outfit. Somewhere inside it was a man.

‘Bit fresh,’ the bundle offered understatedly. John and David asked him if he’d come far.

‘Just from Blea Tarn.’ Blea Tarn was 10 miles away over taxing terrain.

‘Bad over there?’ John asked in what I’d come to recognise was the abbreviated speech of fell walkers.

‘Hands-and-knees job,’ said the man. They nodded knowingly.

‘Be like that here soon.’ They nodded again.

‘Well, best be off,’ announced the man as if he couldn’t spend the whole day jabbering, and trundled off into the white soup.

I watched him go, then turned to suggest that perhaps we should think about retreating to the valley, to a warm hostelry with hot food and cold beer, only to find Price and Partridge dematerialising into the mists 30ft ahead of me. ‘Hey, wait for me!’ I croaked and scrambled after.

We made it to the top without incident. I counted 33 people there, huddled among the fog-whitened boulders with sandwiches, flasks and madly fluttering maps, and tried to imagine how I would explain this to a foreign onlooker — the idea of three-dozen English people having a picnic on a mountain top in an ice storm — and realised there was no way you could explain it.

We trudged over to a rock, where a couple kindly moved their rucksacks and shrank their picnic space to make room for us.

Then we sat and delved among our brown bags in the piercing wind, cracking open hard-boiled eggs with numbed fingers, sipping warm pop, eating floppy cheese-and-pickle sandwiches, and staring into an impenetrable murk we had spent three hours climbing through to get here, and I thought, I seriously thought: God, I love this country.

NOTES From A Small Island: Journey Through Britain by Bill Bryson (Black Swan, £8.99).To order a copy for £7.19 (20 per cent discount) visit mailbookshop.co.uk or call 0844 571 0640, p&p is free on orders over £15.The offer is valid until August 24, 2016.

Bill Bryson's latest book - The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes From a Small Island, the sequel to Notes From A Small Island - was published last year.

Read more: The man who'll make you love Britain anew even the bits we all moan about | Daily Mail Online

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1951, Bryson visited the UK in 1973, fell in love with the place and decided to stay. He fell in love with a nurse at the psychiatric hospital he worked at and the pair eventually got married. After spending a few years in Iowa, the pair returned to Britain in 1977. Bryson eventually became a newspaper journalist and the couple had children.

In 1995, the family went to live in Hanover in New Hampshire. Before moving there, Bryson took a trip around the UK and wrote of his travels in a book he published in 1996 - Notes From A Small Island. The book became a bestseller in the UK.

During this trip he insisted on using only public transport, but failed on two occasions: in Oxfordshire and on the journey to John o' Groats he had to rent a car. He also re-visits Virginia Water where he worked at the Holloway Sanatorium when he first came to Britain in 1973.

On his way, Bryson provides historical information on the places he visits, and expresses amazement at the heritage in Britain, stating that there were 445,000 listed historical buildings, 12,000 medieval churches, 1,500,000 acres (600,000 ha) of common land, 120,000 miles (190,000 km) of footpaths and public rights-of-way, 600,000 known sites of archaeological interest and that in his Yorkshire village at that time, there were more 17th century buildings than in the whole of North America.

In the end, Bryson and his family didn't stay in New Hampshire for long. In 2003 they moved back to the UK and Bryson eventually made himself a British citizen. In 2005 he was made chancellor of Durham University, and became president of the Campaign to Protect Rural England in 2007.

Apart from Notes from a Small Island, Bryson has also written books on science, the English language and other non-fiction topics, including other travel books - he has written about his travels around Australia, Europe and the Appalachian Trail.

His latest book - The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes From a Small Island, the sequel to Notes From A Small Island - was published last year.

Twenty years on, here are some of the most joyous highlights from Notes From A Small Island...

The man who'll make you love Britain anew (even the bits we all moan about): Twenty years on, the most joyous highlights from BILL BRYSON'S Notes From a Small Island in a series which will lift your heart

By Bill Bryson For Daily Mail

13 August 2016

Bill Bryson: The Anglo-American author's book about his travels around the UK became a bestseller

There is a small, tattered clipping that I sometimes carry with me and pull out for purposes of private amusement. It’s a weather forecast from the Western Daily Mail and it says, in toto: ‘Outlook: Dry and warm, but cooler with some rain.’

There you have in a single pithy sentence the British weather captured to perfection: dry but rainy with some warm/cool spells. The Western Daily Mail could run that forecast every day — for all I know, it may — and scarcely ever be wrong.

To an outsider the most striking thing about the British weather is that there isn’t very much of it. All those phenomena that elsewhere give nature an edge of excitement, unpredictability and danger — tornadoes, monsoons, raging blizzards, run-for-your-life hailstorms — are almost wholly unknown in the British Isles, and this is just fine by me.

Bill Bryson has started a series on life in Britain with all of its oddities and customs

I like wearing the same type of clothing every day of the year. I appreciate not needing air conditioning or mesh screens on the windows to keep out the kind of insects and flying animals that drain your blood or eat away your face while you are sleeping. I like knowing that so long as I do not go walking up Ben Nevis in carpet slippers in February I will almost certainly never perish from the elements in this soft and gentle country.

I mention this because as I sat eating my breakfast in the dining room of the Old England Hotel in Bowness-on-Windermere, two days after leaving Morecambe, I was reading an article in The Times about an unseasonable snowstorm — a ‘blizzard’, The Times called it — that had ‘gripped’ parts of East Anglia.

According to The Times report, the storm had covered parts of the region with ‘more than 2in of snow’ and created ‘drifts up to 6in high’.

In response to this, I did something I had never done before: I pulled out my notebook and drafted a letter to the editor in which I pointed out, in a kindly, helpful way, that 2in of snow cannot possibly constitute a blizzard and that 6in of snow is not a drift.

A blizzard, I explained, is when you can’t get your front door open. Drifts are things that make you lose your car until spring. Cold weather is when you leave part of your flesh on doorknobs, mailbox handles and other metal objects.

Then I crumpled the letter up because I realised I was in danger of turning into one of the Colonel Blimp types who sat around me, eating cornflakes or porridge with their blimpish wives, and without whom hotels like the Old England would not be able to survive.

I was in Bowness because I had two days to kill until I was to be joined by two friends from London with whom I was going to spend the weekend walking. I was looking forward to that, but rather less to the prospect of another long, purposeless day in Bowness, pottering about trying to fill the empty hours till tea.

There are, I find, only so many windowsful of tea towels, Peter Rabbit dinnerware and patterned jumpers I can look at before my interest in shopping palls, and I wasn’t at all sure that I could face another day of poking about in this most challenging of resorts.

I had come to Bowness more or less by default since it is the only place inside the Lake District National Park with a railway station.

Besides, the idea of spending a couple of quiet days beside the tranquil beauty of Windermere, and wallowing in the plump comforts of a gracious (if costly) old hotel, had seemed distinctly appealing from the vantage of Morecambe Bay.

But now, with one day down and another to go, I was feeling stranded and fidgety, like someone at the end of a long period of convalescence.

Ambleside in the Lake District

At least, I reflected optimistically, the unseasonable 2in of snow that had brutally lashed East Anglia, causing chaos on the roads and forcing people to battle their way through perilous snowdrifts, some as high as their ankletops, had mercifully passed this corner of England by.

Here, the elements were benign and the world outside the dining-room window sparkled weakly under a pale wintry sun.

I decided to take the lake steamer to Ambleside. This would not only kill an hour and let me see the lake, but deliver me to a place rather more like a real town and less like a misplaced seaside resort than Bowness.

In Bowness, I had noted the day before, there are no fewer than 18 shops where you can buy jumpers and at least 12 selling Peter Rabbit stuff, but just one butcher’s.

Ambleside, though hardly unfamiliar with the possibilities for enrichment presented by hordes of passing tourists, did at least have an excellent bookshop and any number of outdoor shops, which I find hugely if inexplicably diverting — I can spend hours looking at rucksacks, kneesocks, compasses and survival rations, then go to another shop and look at precisely the same things all over again.

So it was with a certain animated keenness that I made my way to the steamer pier after breakfast.

Alas, I discovered the steamers run only in summer, which seemed shortsighted on this mild morning because even now Bowness gently teemed with trippers.

Members of the public enjoy the hot sunny weather at Goodrington in Devon

So I was forced, as a fallback, to pick my way through the scattered, shuffling throngs to the little ferry that shunts back and forth between Bowness and the old ferry house on the opposite shore. It travels only a few hundred yards, but it does at least run all year.

A modest line-up of cars was patiently idling on the ferry approach, and there were eight or ten walkers as well, all with Mustos, rucksacks and sturdy boots. One fellow was even wearing shorts — always a sign of advanced dementia in a British walker.

Walking — walking, that is, in the British sense — was something I had come into only relatively recently.

I was not yet at the point where I would wear shorts with many pockets, but I had taken to tucking my trousers into my socks (though I have yet to find anyone who can explain what benefits this confers, other than making one look serious and committed). I remember when I first came to Britain wandering into a bookstore and being surprised to find a section dedicated to ‘Walking Guides’.

This struck me as faintly comical — where I came from people did not require written instructions to achieve locomotion — but gradually I learned that there are two kinds of walking in Britain: the everyday kind that gets you to the pub and, all being well, home again, and the kind that involves stout boots, Ordnance Survey maps in plastic pouches, rucksacks with sandwiches and flasks of tea, and, in its terminal phase, the wearing of khaki shorts in inappropriate weather.

For years, I watched these walker types toiling off up cloud-hidden hills in wet and savage weather and presumed they were genuinely insane. And then my old friend John Price, who had grown up in Liverpool and spent his youth doing foolish things on sheer-faced crags in the Lakes, encouraged me to join him and a couple of his friends for an amble — that was the word he used — up Haystacks one weekend.

To an outsider the most striking thing about the British weather is that there isn’t very much of it - and that is how Bill Bryson likes it

I think it was the combination of those two untaxing-sounding words, ‘amble’ and ‘Haystacks’, and the promise of lots of drink afterwards, that lulled me from caution.

‘Are you sure it’s not too hard?’ I asked.

‘Nah, just an amble,’ John insisted.

Well, of course it was anything but an amble. We clambered for hours up vast, perpendicular slopes, over clattering scree and lumpy tussocks, round towering citadels of rock, and emerged at length into a cold, bleak, lofty nether world so remote and forbidding that even the sheep were startled to see us.

Beyond it lay even greater and remoter summits that had been invisible from the ribbon of black highway thousands of feet below,

John and his chums toyed with my will to live in the cruellest possible way; seeing me falling behind, they would lounge around on boulders, smoking and chatting and resting, but the instant I caught up with them with a view to falling at their feet, they would bound up refreshed and, with a few encouraging words, set off anew with large, manly strides, so that I had to stumble after and never got a rest.

I gasped and ached and sputtered, and realised that I had never done anything remotely this unnatural before and vowed never to attempt such folly again.

Then, just as I was about to lie down and call for a stretcher, we crested a final rise and found ourselves abruptly, magically, on top of the earth, on a platform in the sky, amid an ocean of swelling summits.

The best bits of Bill Bryson's Notes from a Small Island are being presented in a series

I had never seen anything half so beautiful before. ‘F*** me,’ I said in a moment of special eloquence and realised I was hooked. Ever since then I had come back whenever they would have me, and never complained and even started tucking my trousers in my socks. I couldn’t wait for the morrow.

The ferry docked and I shuffled on board with the others. Windermere looked serene and exceedingly fetching in the gentle sunshine.

Unusually there wasn’t a single pleasure boat disturbing its glassy calmness. To say that Windermere is popular with boaters is to flirt recklessly with understatement.

Some 14,000 powerboats — let me repeat that number: 14,000 — are registered to use the lake. On a busy summer’s day, as many as 1,600 powerboats may be out on the water at any one time, a good many of them zipping along at up to 40 miles an hour with water-skiers in tow.

This is in addition to all the thousands of other floating objects that may be out on the water and don’t need to register — dinghies, sailboats, sailboards, canoes, inflatables, li-los, various excursion steamers and the old chugging ferry I was on now — all of them searching for a boat-sized piece of water.

It is all but impossible to stand on a lakeside bank on an August Sunday watching water-skiers slicing through packed shoals of dinghies and other floating detritus and not end up with your mouth open and your hands on your head. Yet even at its worst, the Lake District remains more charming and less rapaciously commercialised than many famed beauty spots in more spacious countries.

And away from the crowds it retains pockets of sheer perfection, as I found when the ferry nosed into its landing and we tumbled off.

For a minute the landing area was a hive of activity as one group of cars got off, another got on and the eight or ten foot passengers departed in various directions.

All those phenomena that elsewhere give nature an edge of excitement, unpredictability and danger — tornadoes, monsoons, raging blizzards, run-for-your-life hailstorms — are almost wholly unknown in the British Isles

Then all was blissful silence. I followed a pretty, wooded road around the lake’s edge before turning inland and heading for Near Sawrey.

Near Sawrey is the home of Hilltop, the cottage where the inescapable Beatrix Potter drew her sweet little watercolours and contrived her soppy stories. For most of the year, it is overrun with tourists from far and wide.

Such indeed is Hilltop’s alarming popularity that the National Trust doesn’t even actively advertise it any more. Yet still the visitors come. Two coaches were disgorging chattering white-haired occupants when I arrived and the main car park was already nearly full.

I had been to Hilltop the year before, so I wandered past it and up a little-known track to a tarn on some high ground behind it. Old Mrs Potter used to come up to this tarn regularly to thrash about on it in a rowing boat — whether for healthful exercise or as a kind of flagellation I don’t know — but it was very lovely and seemingly quite forgotten. I had the distinct feeling that I was the first visitor to venture up there for years.

Across the way, a farmer was mending a stretch of fallen wall and I stood and watched him for a while from a discreet distance, because if there is one thing nearly as soothing to the spirit as mending a drystone wall it is watching someone else doing it.

I remember once, not long after we moved to the Yorkshire Dales, going for a stroll and happening across a farmer I knew slightly who was rebuilding a wall on a remote hill. It was a rotten January day full of drifting fog and rain and the thing is there wasn’t any discernible point in his rebuilding the wall.

The weather plays a major part of Britain's culture, Bill Bryson writes about

He owned the fields on either side and in any case there was a gate that stood permanently open between the two, so it wasn’t as if the wall had any real function. I watched him awhile and finally asked him why he was standing out in a cold rain rebuilding the wall.

He looked at me with that special pained look Yorkshire farmers save for onlookers and other morons and said: ‘Because it’s fallen down, of course.’

From this I learned, first of all, never to ask a Yorkshire farmer any question that can’t be answered with ‘pint of Tetley’s’ and that one of the primary reasons so much of the British landscape is so unutterably lovely and timeless is that most farmers, for whatever reason, take the trouble to keep it that way.

By 11 the next morning, when John Price and a very nice fellow named David Partridge rolled up at the hotel in Price’s car, I was waiting for them by the door. I forbade them a coffee stop in Bowness on the grounds that I could stand it no longer, and made them drive to the hotel near Bassenthwaite, where Price had booked us rooms.

There we dumped our bags, had a coffee, acquired three packed lunches from the kitchen, accoutred ourselves in stylish fell-wear and set off for Great Langdale. Now this was more like it.

Despite threatening weather and the lateness of the year, the car parks and verges along the valley were crowded. Everywhere people delved for equipment in boots or sat with car doors open pulling on warm socks and stout boots.

We dressed our feet, then fell in with a straggly army of walkers, all with rucksacks and knee-high woolly socks, and set off for a long, grassy humpback hill called the Band.

We were headed for the fabled summit of Bow Fell, at 2,960ft the sixth-highest of the Lakeland hills.

Walkers ahead of us formed well-spaced dots of slow-moving colour leading to an impossibly remote summit, lost in cloud. As ever, I was quietly astounded to find so many people had been seized with the notion that struggling up a mountainside on a damp Saturday on the winter end of October was fun.

Deckchairs and people sunbathing on the beach in Sidmouth, Devon

We climbed through the grassy lower slopes into ever-bleaker terrain, picking our way over rocks and scree, until we were up among the ragged shreds of cloud that hung above the valley floor perhaps a thousand feet below.

The views were sensational — the jagged peaks of the Langdale Pikes rising opposite and crowding against the narrow and gratifyingly remote valley, laced with tiny, stonewalled fields, and off to the west a swelling sea of hefty brown hills disappearing in mist and low cloud.

As we pressed on the weather severely worsened. The air filled with swirling particles of ice that hit the skin like razor nicks. By the time we neared Three Tarns the weather was truly menacing, with thick fog joining the jagged sleet. Ferocious gusts of wind buffeted the hillside and reduced our progress to a creeping plod.

The fog cut visibility to a few yards. Once or twice we briefly lost the path, which alarmed me as I didn’t particularly want to die up here — apart from anything else, I still had 4,700 unspent Profiles points on my Barclaycard.

Out of the murk ahead emerged what looked disconcertingly like an orange snowman. It proved on closer inspection to be a high-tech hiker’s outfit. Somewhere inside it was a man.

‘Bit fresh,’ the bundle offered understatedly. John and David asked him if he’d come far.

‘Just from Blea Tarn.’ Blea Tarn was 10 miles away over taxing terrain.

‘Bad over there?’ John asked in what I’d come to recognise was the abbreviated speech of fell walkers.

‘Hands-and-knees job,’ said the man. They nodded knowingly.

‘Be like that here soon.’ They nodded again.

‘Well, best be off,’ announced the man as if he couldn’t spend the whole day jabbering, and trundled off into the white soup.

I watched him go, then turned to suggest that perhaps we should think about retreating to the valley, to a warm hostelry with hot food and cold beer, only to find Price and Partridge dematerialising into the mists 30ft ahead of me. ‘Hey, wait for me!’ I croaked and scrambled after.

We made it to the top without incident. I counted 33 people there, huddled among the fog-whitened boulders with sandwiches, flasks and madly fluttering maps, and tried to imagine how I would explain this to a foreign onlooker — the idea of three-dozen English people having a picnic on a mountain top in an ice storm — and realised there was no way you could explain it.

We trudged over to a rock, where a couple kindly moved their rucksacks and shrank their picnic space to make room for us.

Then we sat and delved among our brown bags in the piercing wind, cracking open hard-boiled eggs with numbed fingers, sipping warm pop, eating floppy cheese-and-pickle sandwiches, and staring into an impenetrable murk we had spent three hours climbing through to get here, and I thought, I seriously thought: God, I love this country.

NOTES From A Small Island: Journey Through Britain by Bill Bryson (Black Swan, £8.99).To order a copy for £7.19 (20 per cent discount) visit mailbookshop.co.uk or call 0844 571 0640, p&p is free on orders over £15.The offer is valid until August 24, 2016.

Bill Bryson's latest book - The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes From a Small Island, the sequel to Notes From A Small Island - was published last year.

Read more: The man who'll make you love Britain anew even the bits we all moan about | Daily Mail Online

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook