Why the (left's) propaganda war on UKIP has failed

Frank Furedi Commentator and sociologist

Spiked

6th May 2014

61 comments

Farage’s popularity exposes the aloofness of the political class

The British media and the political class almost never speak from the same script. So their crusade against UKIP and its leader, Nigel Farage, is very interesting. During recent weeks, all the major newspapers and media organisations have devoted considerable resources to exposing this ‘nefarious’ movement. On an almost daily basis, you can read stories about a would-be UKIP parish councillor discovered watching pornography online or an aged party supporter who still believes, rightly, of course, that Britain actually won the Second World War. One exposé after another has reiterated the wisdom of Conservative prime minister David Cameron’s careful, balanced assessment of UKIP’s membership: ‘fruitcakes and loonies and closet racists.’ Yet despite the efforts of a small army of courageous investigative journalists, endlessly trawling social media for quotable UKIP

faux pas, these fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists are still doing well in the polls.

Those attempting to account for the media’s failure to make much of a dent in UKIP’s support usually draw attention to the supposed moral and intellectual inferiority of its supporters. From the standpoint of a Westminster political consultant, the typical UKIP voter is a disgruntled, prejudiced idiot who simply fails to grasp the sophisticated messages of the political oligarchy. ‘We haven’t educated people as to what they are all about – UKIP voters need to be educated’, asserts Glyn Ford, Labour’s former European Parliament leader. Education is what you demand of naughty schoolchildren.

The call to ‘educate’ UKIP voters self-consciously infantilises adult citizens and voters, implicitly reducing them to the status of slow-learning children. From Ford’s perspective, UKIP supporters are clearly his moral inferiors, people who lack the capacity to grasp that perpetuating the status quo is in their best interests. The premise of Ford’s call for educating ‘them’ is best captured by the expression used by the American cultural elite towards their moral inferiors – ‘they don’t get it’. The term expresses a comforting sense of self-flattery – ‘

we get it’. It draws attention to the stupidity of ‘they’.

But if anyone is ‘not getting it’, it’s the inhabitants of the Westminster bubble. They simply do not understand why, on this occasion, the propaganda targeting UKIP has had so little effect. Sections of the media have dubbed Nigel Farage the Teflon man of British public life. From their perspective, it seems as if nothing that gets thrown at him sticks. What this analysis fails to grasp is that what is at issue is not the unique qualities of Nigel Farage, but the feeble character of the rhetorical assault directed at him.

The invectives hurled at Farage have been smirking, patronising and lazy. Deputy prime minister Nick Clegg sounded as if he was addressing his media trainer rather than the British public during his so-called debates with Farage. The constant overuse of terms like ‘racist’ trivialises this terrible worldview and deprives it of meaning. What mainstream politicians and the media don’t get is that the very attempt to humiliate UKIP, reducing it to the role of xenophobic simpletons, is seen by a section of the public as an expression of contempt towards them.

Last Sunday, an opinion poll indicated that UKIP continues to enjoy a lead in voting intentions for the upcoming European elections, even though most people believe that the party contains racists. This poll can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Some will draw the conclusion that Britain is the most racist society in the world, a place where popular prejudice drives public life. This seems to be the interpretation adopted by the consultants advising the political class. That is why the constant political-class refrain about these ‘nasty xenophobes’ is punctuated by advice that it is a ‘mistake’ to condemn UKIP and their voters as racist. This call to desist from constantly playing the racist card is founded on hypocrisy and bad faith. It is based on the calculation that would-be UKIP voters are indeed driven by intense hatred and prejudice, and reminding them of the racism of their party would merely consolidate support for it.

From the standpoint of Britain’s political oligarchy, anyone who fails to adhere to its cosmopolitan cultural doctrine must indeed be a bigot or a racist. The description of ordinary people as racist and bigoted is an integral element of the British establishment’s vocabulary.

It’s just that politicians have now drawn the conclusion that it is best to keep their contemptuous views of the electorate to themselves. They remember poor Gordon Brown’s ‘Bigotgate’ moment, when, during the 2010 General Election campaign, he referred to a 65-year-old woman who asked him about immigration as a ‘bigoted woman’. Unfortunately for Brown, his microphone was still on as he made his outburst and the rest is history. The lesson drawn from Bigotgate is that it is best not to refer to the millions of bigots who make up a significant portion of the electorate as what they really are - in the prime minister’s words, ‘fruitcakes and loonies and closet racists’.

Another way of interpreting last Sunday’s poll is that ‘racist’ has become a promiscuously used term of abuse. When some people hear an act described as racist, they associate it with the attempt to assign a character flaw to an individual or a group. ‘Racist’ has become a term that is applied routinely to any target of displeasure. The use of the word racism is rarely confined to attitudes and acts of oppression. It is used as a cultural marker to underline one’s morally superior qualities and, by implication, to devalue those afflicted with prejudice. That is why there is such a relentless quest to unearth ‘racist’ remarks and to reinterpret gestures and sentiments as racist. The very fact that racism and racist language now need to be exposed indicates that racism is not a public act. Nor does an act of racism require subjective intent. That’s what the Orwellian concept of ‘unwitting racism’ is all about.

Politics of bad faith

It is not merely the case that, when it comes to UKIP, the establishment doesn’t get it. The establishment also

can’t get it, because to acknowledge the genuine dynamic behind UKIP’s support would mean facing up to its own isolation from large sections of the British public. In reality, the failure of the current media campaign against UKIP shows that the members of the political establishment are confronted by a substantial group of voters whose values and way of life contradict their social etiquette and cultural assumptions. However, rather than face up to its isolation from a significant section of the electorate, the political class continues to evade taking responsibility for its own failures.

The main reason the parliamentary parties have failed to contain UKIP’s rise in the polls is because they lack the arguments to win over the electorate. That is why it is far from clear what Ford’s proposed education of voters would teach. Time and again, the establishment argues that UKIP is merely a negative party of protest with no positive objective. No doubt UKIP lacks a robust forward-looking manifesto and a positive vision of the future. But what do the other parties stand for? One would need a PhD in the finer nuances of theology to grasp the positive principles that define Labour or the Conservatives. Indeed, anyone listening to major parliamentary figures today will be immediately struck by the energy they invest in evading discussing points of principle.

Until now, the close symbiotic relationship between the media and the political class has helped to obscure the fact that these little emperors have a very limited wardrobe. Whatever one thinks of UKIP, its challenge has exposed the flabby and self-referential worldview of the second-rate Anthony Trollope characters that inhabit the Westminster world.

Back in the nineteenth century, the Conservative politician Benjamin Disraeli drew attention to the existence of ‘two different nations [within British society], between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets’. Disraeli was referring to the division between rich and poor. Whatever one thinks of Disraeli, he did not write off those inhabiting a different world; he sought to convince his fellow parliamentarians that it was their duty to understand those who lived in circumstances very different to themselves, and to make an effort to communicate with them.

In the twenty-first century, what separates the ‘two nations’ in Britain are cultural attitudes and values. Unlike Disraeli, who openly acknowledged the reality of his time, today’s political oligarchy hides behind empty rhetoric. Unlike Disraeli, who could empathise with the other nation, the current establishment has only contempt for those ‘fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists’. Whatever happens to UKIP, the problems thrown up by the co-existence of two nations will continue to haunt British society.

Frank Furedi’s latest book,

First World War: Still No End in Sight, is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from

Amazon (UK).) Visit his website

here.

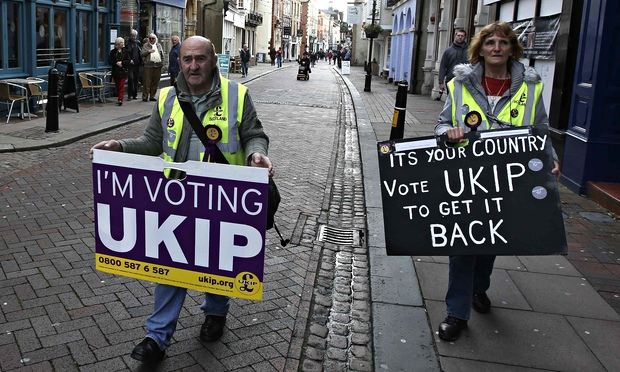

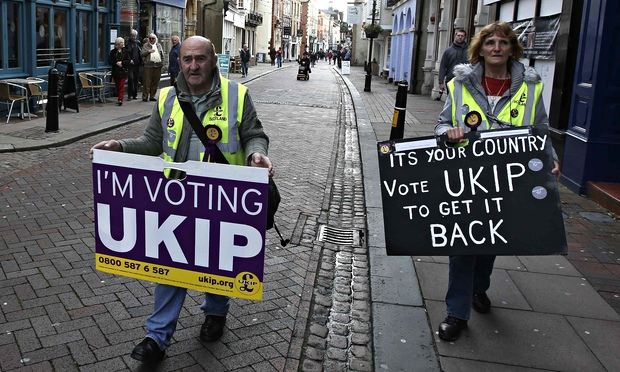

Picture: Wikimedia / Euro Realist Newsletter

Why the propaganda war on UKIP has failed | British politics | Politics | spiked