The Franklin Expedition set sail from England in 1845. Its mission was to traverse the Northwest Passage above Canada.

The Royal Navy ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were assigned this task.

After a few early fatalities the two ships became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island in the Canadian Arctic. The entire expedition complement, Franklin and 128 men, was lost.

Pressed by Franklin's wife and others, the Admiralty launched a search for the missing expedition in 1848.

We do not know too much about the fate that befell the men, but there is one thing we do know. They resorted to cannibalism to survive...

Very British cannibals: How an epic Navy voyage across the Arctic came to a truly sinister end

By Annabel Venning

26th June 2009

Daily Mail

We cannot know when it started, nor who took the gruesome decision, but some time in May 1848, British sailors from HMS Erebus and HMS Terrorbegan butchering and eating their comrades.

Did they kill the living, picking out the weak, the young and the expendable? Or did they confine their attentions to the dead? That, too, history cannot tell. But one thing is certain,the sailors ate their shipmates - not just one or two of them, but 40 or 50. Perhaps more.

The British seamen carefully and deliberately used their knives to strip the flesh from men who had been their comrades. Their sharp blades left tell-tale marks on the victims' bones - marks that have endured to this day.

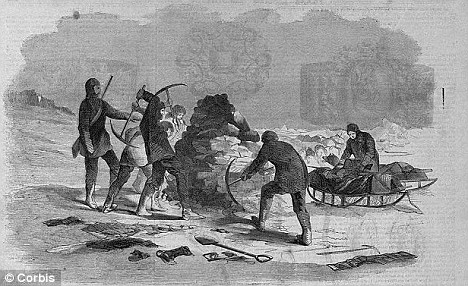

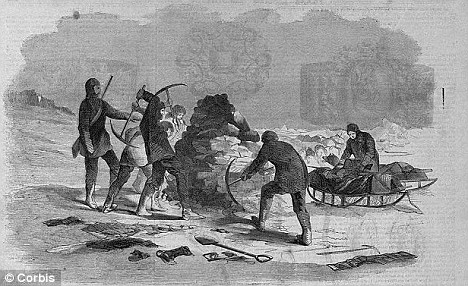

Terrible fate: A painting of British explorer Sir John Franklin and crew dying by their ice-bound boat

To remove the maximum amount of flesh, they cut the bodies into joints, removing the muscle tissue. They even cracked open the larger bones to extract the marrow. And they didn't stop there.

In the handful of similarly gruesome cases where desperate men have turned to cannibalism to stave off starvation, the heads and hands of the victims are usually removed and discarded, too human to be eaten. The men of Erebus and Terror were not so squeamish. They took the heads, ripped off the jaw-bones and stove in the bases of the skulls to get at the brain.

After the heads were done, they scavenged for scraps, flaying the flesh even from the fingers, stripping off every last remnant.

Precisely how many men took part in this barbaric banquet we will never know. No one lived to tell. There are still those who insist it did not happen. But forensic science is a precise art, and the evidence is overwhelming. The Arctic expedition of Captain Sir John Franklin ended in cannibalism on a scale beyond even the darkest rumours of the time.

So how did a quest that set out for the noblest of causes under the leadership of a hero end in such savagery? When Sir John embarked on his final voyage to the Arctic in 1845, he was already a veteran of the battle of Trafalgar, whose formidable exploits at sea and on ice had earned him a reputation for endurance and courage.

In 1819, Franklin, then a naval lieutenant, had led an expedition to the Arctic that ran out of supplies. The starving men were reduced to eating their leather boots. Ten men died of starvation and hypothermia and at least one was murdered by his comrades.

Nonetheless, the expedition returned and Franklin became an Arctic celebrity, 'the man who ate his boots'. He led another Arctic expedition in 1825, cementing his reputation as a skilled navigator, scientist and leader, and was knighted on his return.

Franklin rejoined the naval service and served as a ship's captain in the Mediterranean, but he yearned to return to the Arctic, urged on by his second wife, Jane. Having married the romantic hero who'd been famed for his bravery, she would not settle for being the wife of a mere naval captain.

Early days: Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin sets off in a low boat with a crew, supplies and dogs around 1818

But Franklin missed out on the next few Arctic missions. Instead he was appointed governor of Tasmania, where his humane, reformist attitudes brought him into conflict with the local establishment, causing the colonial office to recall him.

So he was back in London in 1844 when a proposal was laid before the Admiralty for an expedition to 'complete the discovery of a North-West Passage', the fabled sea route through the Arctic ice, for which mariners had been searching for 300 years.

If it existed, it would provide a profitable short-cut for ships heading from Europe to the West Coast of America and China.

However, the real object of the expedition was to take magnetic readings at or near the magnetic North Pole as the final element in a global 'imperial science' project to finesse the skill of navigation aboard British ships.

The readings were crucial because of the way the earth's magnetic field affects the functioning of the compass, critical for a maritime empire. Franklin, aided by Jane, successfully lobbied for command of the expedition.

Although he was nearly 60 and overweight - at 5ft 6in and 15 stone - he had extensive Arctic experience, leadership and was a first-rate magnetic scientist.

Franklin appointed Francis Crozier, an Antarctic veteran,as his second in command. On May 19, 1845, the two ships, laden with 129 men and enough magnetic hardware to equip an observatory, went to sea buoyed up by euphoria and good wishes.

Long-sought clues: Men under the direction of Captain McClintock open a cairn left by Sir John Franklin and his expedition members

There were a few doubters on land, though. One Arctic veteran predicted disaster, saying that Franklin would 'form the nucleus of an iceberg'.

It was a warning that was to prove all too prophetic.

In July, Franklin wrote home telling Jane that he might be away for three years and that he put his faith in God. These were his last words to reach the outside world.

Few were concerned when Franklin failed to report after his first year in the Arctic. He had urged his friends and family not to expect him home until his supplies had run out. He told the captain of a whaling ship he encountered in July 1845 that he had enough provisionsfor five years, but that he could eke them out for seven.

The Admiralty finally began to think about sending a relief mission in late 1846, prompted by Lady Franklin. However, some Arctic experts thought it 'absurd to entertain the smallest degree of alarm'. It would suffice to offer rewards for information to whalers and traders in Hudson Bay, south of the Arctic.

But the whalers had no idea where to look. Franklin's course was a complete mystery.

Not until the spring of 1848 was a search expedition sent,headed by Arctic veteran Sir John Richardson and accompanied by Dr John Rae of the Hudson's Bay Company.

They headed down the Mackenzie River in the North-West territories, coasted east but found nothing.

Two more ships sailed for the Arctic to make a rescue effort, but they, too, found no trace of the lost expedition.

Desperate that her husband must be found, Jane recruited public opinion to her cause, cultivating allies within the Admiralty.

Over the next decade, ship after ship, British and American, was sent to trawl the icy seas, long after any realistic prospect of finding Franklin alive had receded.

Enthusiastic officers pushed themselves to the limits of human endurance. Scurvy often took hold and several died. Yet for all their heroism, they found nothing.

Explorer action: Members of Franklin's team slide down a snow-covered hill with their gear while dogs race alongside in an expedition around 1825

Then an expedition in 1850 found evidence of Franklin's first winter camp on Beechey Island in what is now the Canadian arctic: food tins, the graves of three men who had died early in 1846, but no written records.

Years past and it was not until the autumn of 1854 that the fate of Franklin and his 129 men was finally uncovered, when terrible news reached Britain from the Arctic.

John Rae, on another of his Hudson's Bay expeditions, had encountered a party of Inuit who had trophies from Franklin's kitin their possession: a gold cap band and Franklin's order of Knighthood.

The Inuits told Rae that they had not met the British sailors, but knew others who had. They said that the white men had all died some years before, and the all-important paper records had been thrown away.

There was worse. Rae's contacts told him that when a large group of survivors had been encountered by Inuits on nearby King William Island some years earlier, they had been in a poor condition, afflicted with scurvy.

The Inuits also told the Englishman that human bones had been found, and as Rae later reported it: 'From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles,it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource - cannibalism - as a means of prolonging existence.'

Rae's news horrified the public. Charles Dickensrefused to accept it, dismissing the Inuit account as 'the chatter of a gross handful of uncivilised people'.

He speculated that the 'covetous, treacherous and cruel Inuit' had murdered the survivors. It was inconceivable that a party led by British officers could have stooped to cannibalism: gentlemen did not eat human flesh.

Although resigned to widowhood, Jane remained anxious to know how her husband's expedition had come to such an end.

As the Admiralty would no longer commit ships or men to an expedition, Jane successfully funded one herself with the help of a public appeal.

Enlarge

Holy grail: A chart of Franklin and other explorers' discoveries in their attempts to find the Northwest Passage between Europe to Asia

If nothing else, she yearned for evidence that Franklin had discovered the North-West Passage before his death.

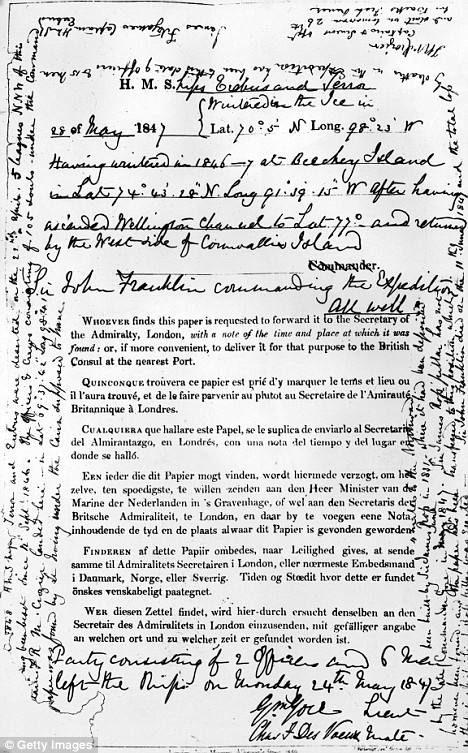

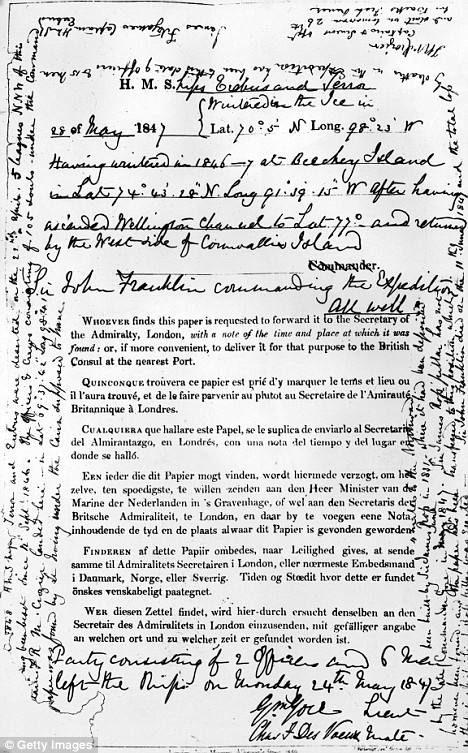

Finally, in May 1859, near a place called Victory Point, her search expedition under the command of a man named Francis McClintockfound a cylindrical tin containing what appeared to be a written record of the Franklin expedition.

'Having wintered in 1846-7 at Beechey Island - All well,' stated the record confidently. Nearby, another copy was found with a hastily added note that told a very different tale.

'1848, HM Ship Terror and Erebus were deserted on April 22 having been beset [by ice] since September 12, 1846 - Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847, and the total loss by deaths in the expedition has been to this date nine officers and 15 men. Start tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River.'

There was no claim that the expedition had discovered the North-West Passage, but it did reveal that Franklin had not lived to witness his expedition dissolve into savagery.

Heading south by sledge, McClintock and his men reached King William Island. They came across the skeletal remains of a fully clothed white man, lying face down.

Piecing together all the evidence, it is now possible to plot how events must have unfolded.

After Franklin's death, his men had marched south across the pack ice in a desperate quest for landfall. They would have been weakened by scurvythat left them susceptible to pneumonia, and ill-prepared for a march dragging sledges after three years on a ship.

Once the men realised their fate, the bounds of civilised behaviour were loosed. The majority remained on King William Island.

Rae's Inuit witnesses had spoken of a large camp with graves, cannibalised bodies and skulls.

A party would then have headed east. The survivors met an Inuit hunting party in Washington Bay.

Around 40 men were present, all suffering from scurvy, and the Inuit were convinced they saw evidence of cannibalism: an Inuit hunter had told Rae that the men had boots filled with cooked human flesh.

How long did this cannibalism sustain the starving survivors? We cannot know, but it is likely all were dead before the winter of 1848.

The official search for Franklin had cost £600,000 - the total amount spent by 1860 was nearly £2million. Britain had to admit defeat.

Enlarge

Part of the trail: The 'All Well' document signed by Franklin in May 1847

In previous years, much had been achieved and great glory had been gained in the frozen north, but no more brave men would be sent to die there.

It was not until 1981 that a modern day expedition stumbled on the final proof of what had taken place.

They uncovered a human femur with knife cuts, a broken skull and a disproportionate quantity of limb bones suggesting that Franklin's men had been carrying the most portable joints with them as they marched.

In 1992, a new Franklin site was discovered. Here, human bones were found scattered. Some 25 per cent showed evidence that they had been cut with steel knives, consistent with chopping and defleshing for consumption. Three major bones had been broken in a manner that would expose the nutritious bone marrow.

Jane Franklin succeeded in enshrining her husband in public memory as a great explorer, he and his men portrayed as heroes who had willingly sacrificed their lives for the greater good.

But forensic science has proved beyond doubt the appalling fate of her husband's crew - men who died in the most horrific circumstances, their hands stained with the blood of their comrades.

Only one question remains: did the Franklin party kill and eat the living, or simply cannibalise the dead? It is a riddle that lies buried for ever amid the icy wastes of the Arctic.

• Franklin - Tragic Hero Of Polar Navigation by Andrew Lambert, Faber & Faber, £20.

dailymail.co.uk

The Royal Navy ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were assigned this task.

After a few early fatalities the two ships became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island in the Canadian Arctic. The entire expedition complement, Franklin and 128 men, was lost.

Pressed by Franklin's wife and others, the Admiralty launched a search for the missing expedition in 1848.

We do not know too much about the fate that befell the men, but there is one thing we do know. They resorted to cannibalism to survive...

Very British cannibals: How an epic Navy voyage across the Arctic came to a truly sinister end

By Annabel Venning

26th June 2009

Daily Mail

We cannot know when it started, nor who took the gruesome decision, but some time in May 1848, British sailors from HMS Erebus and HMS Terrorbegan butchering and eating their comrades.

Did they kill the living, picking out the weak, the young and the expendable? Or did they confine their attentions to the dead? That, too, history cannot tell. But one thing is certain,the sailors ate their shipmates - not just one or two of them, but 40 or 50. Perhaps more.

The British seamen carefully and deliberately used their knives to strip the flesh from men who had been their comrades. Their sharp blades left tell-tale marks on the victims' bones - marks that have endured to this day.

Terrible fate: A painting of British explorer Sir John Franklin and crew dying by their ice-bound boat

To remove the maximum amount of flesh, they cut the bodies into joints, removing the muscle tissue. They even cracked open the larger bones to extract the marrow. And they didn't stop there.

In the handful of similarly gruesome cases where desperate men have turned to cannibalism to stave off starvation, the heads and hands of the victims are usually removed and discarded, too human to be eaten. The men of Erebus and Terror were not so squeamish. They took the heads, ripped off the jaw-bones and stove in the bases of the skulls to get at the brain.

After the heads were done, they scavenged for scraps, flaying the flesh even from the fingers, stripping off every last remnant.

Precisely how many men took part in this barbaric banquet we will never know. No one lived to tell. There are still those who insist it did not happen. But forensic science is a precise art, and the evidence is overwhelming. The Arctic expedition of Captain Sir John Franklin ended in cannibalism on a scale beyond even the darkest rumours of the time.

So how did a quest that set out for the noblest of causes under the leadership of a hero end in such savagery? When Sir John embarked on his final voyage to the Arctic in 1845, he was already a veteran of the battle of Trafalgar, whose formidable exploits at sea and on ice had earned him a reputation for endurance and courage.

In 1819, Franklin, then a naval lieutenant, had led an expedition to the Arctic that ran out of supplies. The starving men were reduced to eating their leather boots. Ten men died of starvation and hypothermia and at least one was murdered by his comrades.

Nonetheless, the expedition returned and Franklin became an Arctic celebrity, 'the man who ate his boots'. He led another Arctic expedition in 1825, cementing his reputation as a skilled navigator, scientist and leader, and was knighted on his return.

Franklin rejoined the naval service and served as a ship's captain in the Mediterranean, but he yearned to return to the Arctic, urged on by his second wife, Jane. Having married the romantic hero who'd been famed for his bravery, she would not settle for being the wife of a mere naval captain.

Early days: Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin sets off in a low boat with a crew, supplies and dogs around 1818

But Franklin missed out on the next few Arctic missions. Instead he was appointed governor of Tasmania, where his humane, reformist attitudes brought him into conflict with the local establishment, causing the colonial office to recall him.

So he was back in London in 1844 when a proposal was laid before the Admiralty for an expedition to 'complete the discovery of a North-West Passage', the fabled sea route through the Arctic ice, for which mariners had been searching for 300 years.

If it existed, it would provide a profitable short-cut for ships heading from Europe to the West Coast of America and China.

However, the real object of the expedition was to take magnetic readings at or near the magnetic North Pole as the final element in a global 'imperial science' project to finesse the skill of navigation aboard British ships.

The readings were crucial because of the way the earth's magnetic field affects the functioning of the compass, critical for a maritime empire. Franklin, aided by Jane, successfully lobbied for command of the expedition.

Although he was nearly 60 and overweight - at 5ft 6in and 15 stone - he had extensive Arctic experience, leadership and was a first-rate magnetic scientist.

Franklin appointed Francis Crozier, an Antarctic veteran,as his second in command. On May 19, 1845, the two ships, laden with 129 men and enough magnetic hardware to equip an observatory, went to sea buoyed up by euphoria and good wishes.

Long-sought clues: Men under the direction of Captain McClintock open a cairn left by Sir John Franklin and his expedition members

There were a few doubters on land, though. One Arctic veteran predicted disaster, saying that Franklin would 'form the nucleus of an iceberg'.

It was a warning that was to prove all too prophetic.

In July, Franklin wrote home telling Jane that he might be away for three years and that he put his faith in God. These were his last words to reach the outside world.

Few were concerned when Franklin failed to report after his first year in the Arctic. He had urged his friends and family not to expect him home until his supplies had run out. He told the captain of a whaling ship he encountered in July 1845 that he had enough provisionsfor five years, but that he could eke them out for seven.

The Admiralty finally began to think about sending a relief mission in late 1846, prompted by Lady Franklin. However, some Arctic experts thought it 'absurd to entertain the smallest degree of alarm'. It would suffice to offer rewards for information to whalers and traders in Hudson Bay, south of the Arctic.

But the whalers had no idea where to look. Franklin's course was a complete mystery.

Not until the spring of 1848 was a search expedition sent,headed by Arctic veteran Sir John Richardson and accompanied by Dr John Rae of the Hudson's Bay Company.

They headed down the Mackenzie River in the North-West territories, coasted east but found nothing.

Two more ships sailed for the Arctic to make a rescue effort, but they, too, found no trace of the lost expedition.

Desperate that her husband must be found, Jane recruited public opinion to her cause, cultivating allies within the Admiralty.

Over the next decade, ship after ship, British and American, was sent to trawl the icy seas, long after any realistic prospect of finding Franklin alive had receded.

Enthusiastic officers pushed themselves to the limits of human endurance. Scurvy often took hold and several died. Yet for all their heroism, they found nothing.

Explorer action: Members of Franklin's team slide down a snow-covered hill with their gear while dogs race alongside in an expedition around 1825

Then an expedition in 1850 found evidence of Franklin's first winter camp on Beechey Island in what is now the Canadian arctic: food tins, the graves of three men who had died early in 1846, but no written records.

Years past and it was not until the autumn of 1854 that the fate of Franklin and his 129 men was finally uncovered, when terrible news reached Britain from the Arctic.

John Rae, on another of his Hudson's Bay expeditions, had encountered a party of Inuit who had trophies from Franklin's kitin their possession: a gold cap band and Franklin's order of Knighthood.

The Inuits told Rae that they had not met the British sailors, but knew others who had. They said that the white men had all died some years before, and the all-important paper records had been thrown away.

There was worse. Rae's contacts told him that when a large group of survivors had been encountered by Inuits on nearby King William Island some years earlier, they had been in a poor condition, afflicted with scurvy.

The Inuits also told the Englishman that human bones had been found, and as Rae later reported it: 'From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles,it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource - cannibalism - as a means of prolonging existence.'

Rae's news horrified the public. Charles Dickensrefused to accept it, dismissing the Inuit account as 'the chatter of a gross handful of uncivilised people'.

He speculated that the 'covetous, treacherous and cruel Inuit' had murdered the survivors. It was inconceivable that a party led by British officers could have stooped to cannibalism: gentlemen did not eat human flesh.

Although resigned to widowhood, Jane remained anxious to know how her husband's expedition had come to such an end.

As the Admiralty would no longer commit ships or men to an expedition, Jane successfully funded one herself with the help of a public appeal.

Enlarge

Holy grail: A chart of Franklin and other explorers' discoveries in their attempts to find the Northwest Passage between Europe to Asia

If nothing else, she yearned for evidence that Franklin had discovered the North-West Passage before his death.

Finally, in May 1859, near a place called Victory Point, her search expedition under the command of a man named Francis McClintockfound a cylindrical tin containing what appeared to be a written record of the Franklin expedition.

'Having wintered in 1846-7 at Beechey Island - All well,' stated the record confidently. Nearby, another copy was found with a hastily added note that told a very different tale.

'1848, HM Ship

There was no claim that the expedition had discovered the North-West Passage, but it did reveal that Franklin had not lived to witness his expedition dissolve into savagery.

Heading south by sledge, McClintock and his men reached King William Island. They came across the skeletal remains of a fully clothed white man, lying face down.

Piecing together all the evidence, it is now possible to plot how events must have unfolded.

After Franklin's death, his men had marched south across the pack ice in a desperate quest for landfall. They would have been weakened by scurvythat left them susceptible to pneumonia, and ill-prepared for a march dragging sledges after three years on a ship.

Once the men realised their fate, the bounds of civilised behaviour were loosed. The majority remained on King William Island.

Rae's Inuit witnesses had spoken of a large camp with graves, cannibalised bodies and skulls.

A party would then have headed east. The survivors met an Inuit hunting party in Washington Bay.

Around 40 men were present, all suffering from scurvy, and the Inuit were convinced they saw evidence of cannibalism: an Inuit hunter had told Rae that the men had boots filled with cooked human flesh.

How long did this cannibalism sustain the starving survivors? We cannot know, but it is likely all were dead before the winter of 1848.

The official search for Franklin had cost £600,000 - the total amount spent by 1860 was nearly £2million. Britain had to admit defeat.

Enlarge

Part of the trail: The 'All Well' document signed by Franklin in May 1847

In previous years, much had been achieved and great glory had been gained in the frozen north, but no more brave men would be sent to die there.

It was not until 1981 that a modern day expedition stumbled on the final proof of what had taken place.

They uncovered a human femur with knife cuts, a broken skull and a disproportionate quantity of limb bones suggesting that Franklin's men had been carrying the most portable joints with them as they marched.

In 1992, a new Franklin site was discovered. Here, human bones were found scattered. Some 25 per cent showed evidence that they had been cut with steel knives, consistent with chopping and defleshing for consumption. Three major bones had been broken in a manner that would expose the nutritious bone marrow.

Jane Franklin succeeded in enshrining her husband in public memory as a great explorer, he and his men portrayed as heroes who had willingly sacrificed their lives for the greater good.

But forensic science has proved beyond doubt the appalling fate of her husband's crew - men who died in the most horrific circumstances, their hands stained with the blood of their comrades.

Only one question remains: did the Franklin party kill and eat the living, or simply cannibalise the dead? It is a riddle that lies buried for ever amid the icy wastes of the Arctic.

• Franklin - Tragic Hero Of Polar Navigation by Andrew Lambert, Faber & Faber, £20.

dailymail.co.uk