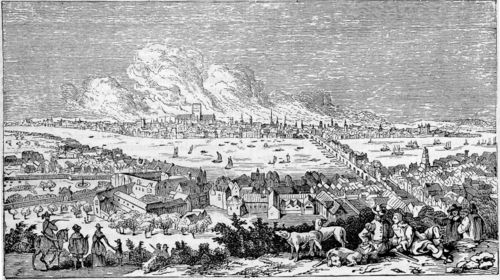

London, as it appeared from Bankside, Southwark, During the Great Fire — Derived from a Print of the Period by Visscher

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the City of London from September 2 to September 5, 1666, and resulted more or less in the destruction of the city. Before this fire, two early fires of London, in 1133/1135 and 1212, both of which destroyed a large part of the city, were known by the same name. Later, the Luftwaffe's fire-raid on the City on 29th December 1940 became known as The Second Great Fire of London.

The fire of 1666 was one of the biggest calamities in the history of London. It destroyed 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, 6 chapels, 44 Company Halls, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House, St Paul's Cathedral, the Guildhall, the Bridewell Palace and other City prisons, the Session House, four bridges across the rivers Thames and Fleet, and three city gates, and made homeless 100,000 people, one sixth of the city's inhabitants at that time. The death toll from the fire is unknown, and is traditionally thought to have been quite small, but a recent book theorizes that thousands may have died in the flames or smoke inhalation.

The fire broke out on Sunday morning, September 2, 1666. It started in Pudding Lane at the house of Thomas Farrinor, a baker to King Charles II. It is likely that the fire started because Farrinor forgot to extinguish his oven before retiring for the evening and that some time shortly after midnight, smouldering embers from the oven set alight some nearby firewood. Farrinor managed to escape the burning building, along with his family, by climbing out through an upstairs window. The baker's housemaid failed to escape and became the fire's first victim.

The London Gazette , front page from Monday 3–10 September 1666, reporting on the Great Fire of London.

Within an hour of the fire starting, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, was awakened with the news. He was unimpressed however, declaring that "a woman might piss it out."

Most buildings in London at this time were constructed of highly combustible materials like wood and straw, and sparks emanating from the baker's shop fell onto an adjacent building. Fanned by a strong wind from the east, once the fire had taken hold it swiftly spread. The spread of the fire was helped by the fact that buildings were built very close together with only a narrow alley between them.

According to a contemporary source:

Then, then the city did shake indeed, and the inhabitants did tremble, and flew away in great amazement from their houses, lest the flames should devour them: rattle, rattle, rattle, was the noise which the fire struck upon the ear round about, as if there had been a thousand iron chariots beating upon the stones. You might see the houses tumble, tumble, tumble, from one end of the street to the other, with a great crash, leaving the foundations open to the view of the heavens.

The progress of the fire might have been stopped, but for the conduct of the Lord Mayor, who refused to give orders for pulling down some houses, without the consent of the owners. Buckets were of no use, from the confined state of the streets.

Destruction

The fire consumed a staggering 13,200 houses and 87 churches, among them the beloved St. Paul's Cathedral. While only 9–16 people were reported as having died in the fire, author Neil Hanson (The Dreadful Judgement) believes the true death toll numbered in the hundreds or the thousands. Hanson believes most of the fatalities were poor people whose bodies were cremated by the intense heat of the fire, and thus their remains were never found. These claims are controversial, however.

The destructive fury of this conflagration is thought never to have been exceeded in the world, by an accidental fire. Within the walls, it consumed almost five-sixths of the whole city; and without the walls it cleared a space nearly as extensive as the one-sixth part left unburnt within. Scarcely a single building that came within the range of the flames was left standing. Public buildings, churches, and dwelling-houses, were alike involved in one common fate.

In the summary account of this vast devastation, given in one of the inscriptions on the Monument, and which was drawn up from the reports of the surveyors appointed after the fire, it is stated, that:

The ruins of the city were 436 acres (1.8 km²), viz. 333 acres (1.3 km²) within the walls, and 63 acres (255,000 m²) in the liberties of the city; that, of the six-and-twenty wards, it utterly destroyed fifteen, and left eight others shattered and half burnt; and that it consumed 400 streets, 13,200 dwelling-houses, 89 churches [besides chapels]; 4 of the city gates, Guildhall, many public structures, hospitals, schools, libraries, and a vast number of stately edifices.

The value of the property destroyed in the fire has been estimated as exceeding ten million pounds. As well as the buildings, this included irreplaceable treasures such as paintings and books: Pepys, for example, gives an account of the loss of the entire stock (and subsequently the financial ruin) of his own preferred bookseller. Despite the immediate destruction caused by the fire, it is nevertheless claimed that its remote effects have benefitted subsequent generations: for instance, it completed the destruction of the Great Plague which, greatly in decline by 1666, had taken the lives of 68,590 people, the previous year; and it also led to the building of some notable new buildings, such as the new St. Paul's Cathedral.

The following remarks regarding the fire are recorded:

Mr. Malcom, in "Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London in the Eighteenth Century," (vol. ii. p. 378), says:

Heaven be praised old London was burnt. Good reader, turn to the ancient prints, in order to see what it has been; observe those hovels convulsed; imagine the chambers within them, and wonder why the plague, the leprosy, and the sweating-sickness raged. Turn then to the prints illustrative of our present dwellings, and be happy. The misery of 1665 must have operated on the minds of the legislature and the citizens, when they rebuilt and inhabited their houses. The former enacted many salutary clauses for the preservation of health, and would have done more, had not the public rejected that which was for their benefit; those who preferred high habitations and narrow dark streets had them. It is only to be lamented that we are compelled to suffer for their folly. These errors are now frequently partially removed by the exertion of the Corporation of London; but a complete reformation is impossible. It is to the improved dwellings composed of brick, the wainscot or papered walls, the high ceilings, the boarded floors, and large windows, and cleanliness, that we are indebted for the general preservation of health since 1666. From that auspicious year the very existence of the natives of London improved; their bodies moved in a large space of pure air; and, finding every thing clean and new around them, they determined to keep them so. Previously-unknown luxuries and improvements in furniture were suggested; and a man of moderate fortune saw his house vie with, nay, superior to, the old palaces of his governors. When he paced his streets, he felt the genial western breeze pass him, rich with the perfumes of the country, instead of the stench described by Erasmus; and looking upward, he beheld the beautiful blue of the air, variegated with fleecy clouds, in place of projecting black beams and plaster, obscured by vapour and smoke.

The streets of London must have been dangerously dark during the winter nights before it was burnt; lanterns with candles were very sparingly scattered, nor was light much better distributed even in the new streets previously to the 18th century. Globular lamps were introduced by Michael Cole, who obtained a patent in July, 1708.

We conclude the illustrations of this day with a singular opinion of the author just quoted. Speaking of the burning of London, he says, "This subject may be allowed to be familiar to me, and I have perhaps had more than common means of judging; and I now declare it to be my full and decided opinion, that London was burnt by government, to annihilate the plague, which was grafted in every crevice of the hateful old houses composing it."

Predictions of a fire in London

There had been much prophecy of a disaster befalling London in 1666, since in Hindu-Arabic numerals it included the number of the Beast and in Roman numerals it was a declining-order list (MDCLXVI). Walter Gostelo wrote in 1658 "If fire make not ashes of the city, and thy bones also, conclude me a liar forever!…the decree is gone out, repent, or burn, as Sodom and Gomorrah!" It seemed to many, coming after a civil war and a plague, Revelation's third horseman.

Prophesies made by Ursula Southeil (Old Mother Shipton), William Lilly, and Nostradamus are also sometimes claimed to predict the Great Fire.

A large fire had already burnt around the northern end of London Bridge in 1632. In 1661, John Evelyn warned of the potential for fire in the city, and in 1664, Charles II wrote to the Lord Mayor of London to suggest that enforcing building regulation would help contain fires.

wikipedia.org