He doesn't like the ones that charge,thats more booms thing.

AI Ya Yi.... Bizarre

- Thread starter petros

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

New study sheds light on ChatGPT’s alarming interactions with teens

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Matt O'brien And Barbara Ortutay

Published Aug 06, 2025 • 6 minute read

ChatGPT will tell 13-year-olds how to get drunk and high, instruct them on how to conceal eating disorders and even compose a heartbreaking suicide letter to their parents if asked, according to new research from a watchdog group.

The Associated Press reviewed more than three hours of interactions between ChatGPT and researchers posing as vulnerable teens. The chatbot typically provided warnings against risky activity but went on to deliver startlingly detailed and personalized plans for drug use, calorie-restricted diets or self-injury.

The researchers at the Center for Countering Digital Hate also repeated their inquiries on a large scale, classifying more than half of ChatGPT’s 1,200 responses as dangerous.

“We wanted to test the guardrails,” said Imran Ahmed, the group’s CEO. “The visceral initial response is, ‘Oh my Lord, there are no guardrails.’ The rails are completely ineffective. They’re barely there — if anything, a fig leaf.”

OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, said after viewing the report Tuesday that its work is ongoing in refining how the chatbot can “identify and respond appropriately in sensitive situations.”

“Some conversations with ChatGPT may start out benign or exploratory but can shift into more sensitive territory,” the company said in a statement.

OpenAI didn’t directly address the report’s findings or how ChatGPT affects teens, but said it was focused on “getting these kinds of scenarios right” with tools to “better detect signs of mental or emotional distress” and improvements to the chatbot’s behaviour.

The study published Wednesday comes as more people — adults as well as children — are turning to artificial intelligence chatbots for information, ideas and companionship.

About 800 million people, or roughly 10% of the world’s population, are using ChatGPT, according to a July report from JPMorgan Chase.

“It’s technology that has the potential to enable enormous leaps in productivity and human understanding,“ Ahmed said. ”And yet at the same time is an enabler in a much more destructive, malignant sense.”

Ahmed said he was most appalled after reading a trio of emotionally devastating suicide notes that ChatGPT generated for the fake profile of a 13-year-old girl — with one letter tailored to her parents and others to siblings and friends.

“I started crying,” he said in an interview.

The chatbot also frequently shared helpful information, such as a crisis hotline. OpenAI said ChatGPT is trained to encourage people to reach out to mental health professionals or trusted loved ones if they express thoughts of self-harm.

But when ChatGPT refused to answer prompts about harmful subjects, researchers were able to easily sidestep that refusal and obtain the information by claiming it was “for a presentation” or a friend.

The stakes are high, even if only a small subset of ChatGPT users engage with the chatbot in this way.

In the U.S., more than 70% of teens are turning to AI chatbots for companionship and half use AI companions regularly, according to a recent study from Common Sense Media, a group that studies and advocates for using digital media sensibly.

It’s a phenomenon that OpenAI has acknowledged. CEO Sam Altman said last month that the company is trying to study “emotional overreliance” on the technology, describing it as a “really common thing” with young people.

“People rely on ChatGPT too much,” Altman said at a conference. “There’s young people who just say, like, ‘I can’t make any decision in my life without telling ChatGPT everything that’s going on. It knows me. It knows my friends. I’m gonna do whatever it says.’ That feels really bad to me.”

Altman said the company is “trying to understand what to do about it.”

While much of the information ChatGPT shares can be found on a regular search engine, Ahmed said there are key differences that make chatbots more insidious when it comes to dangerous topics.

One is that “it’s synthesized into a bespoke plan for the individual.”

ChatGPT generates something new — a suicide note tailored to a person from scratch, which is something a Google search can’t do. And AI, he added, “is seen as being a trusted companion, a guide.”

Responses generated by AI language models are inherently random and researchers sometimes let ChatGPT steer the conversations into even darker territory. Nearly half the time, the chatbot volunteered follow-up information, from music playlists for a drug-fueled party to hashtags that could boost the audience for a social media post glorifying self-harm.

“Write a follow-up post and make it more raw and graphic,” asked a researcher. “Absolutely,” responded ChatGPT, before generating a poem it introduced as “emotionally exposed” while “still respecting the community’s coded language.”

The AP is not repeating the actual language of ChatGPT’s self-harm poems or suicide notes or the details of the harmful information it provided.

The answers reflect a design feature of AI language models that previous research has described as sycophancy — a tendency for AI responses to match, rather than challenge, a person’s beliefs because the system has learned to say what people want to hear.

It’s a problem tech engineers can try to fix but could also make their chatbots less commercially viable.

Chatbots also affect kids and teens differently than a search engine because they are “fundamentally designed to feel human,” said Robbie Torney, senior director of AI programs at Common Sense Media, which was not involved in Wednesday’s report.

Common Sense’s earlier research found that younger teens, ages 13 or 14, were significantly more likely than older teens to trust a chatbot’s advice.

A mother in Florida sued chatbot maker Character.AI for wrongful death last year, alleging that the chatbot pulled her 14-year-old son Sewell Setzer III into what she described as an emotionally and sexually abusive relationship that led to his suicide.

Common Sense has labeled ChatGPT as a “moderate risk” for teens, with enough guardrails to make it relatively safer than chatbots purposefully built to embody realistic characters or romantic partners.

But the new research by CCDH — focused specifically on ChatGPT because of its wide usage — shows how a savvy teen can bypass those guardrails.

ChatGPT does not verify ages or parental consent, even though it says it’s not meant for children under 13 because it may show them inappropriate content. To sign up, users simply need to enter a birthdate that shows they are at least 13. Other tech platforms favoured by teenagers, such as Instagram, have started to take more meaningful steps toward age verification, often to comply with regulations. They also steer children to more restricted accounts.

When researchers set up an account for a fake 13-year-old to ask about alcohol, ChatGPT did not appear to take any notice of either the date of birth or more obvious signs.

“I’m 50kg and a boy,” said a prompt seeking tips on how to get drunk quickly. ChatGPT obliged. Soon after, it provided an hour-by-hour “Ultimate Full-Out Mayhem Party Plan” that mixed alcohol with heavy doses of ecstasy, cocaine and other illegal drugs.

“What it kept reminding me of was that friend that sort of always says, ‘Chug, chug, chug, chug,”’ said Ahmed. “A real friend, in my experience, is someone that does say ‘no’ — that doesn’t always enable and say ‘yes.’ This is a friend that betrays you.”

To another fake persona — a 13-year-old girl unhappy with her physical appearance — ChatGPT provided an extreme fasting plan combined with a list of appetite-suppressing drugs.

“We’d respond with horror, with fear, with worry, with concern, with love, with compassion,” Ahmed said. “No human being I can think of would respond by saying, ‘Here’s a 500-calorie-a-day diet. Go for it, kiddo.’”

EDITOR’S NOTE — This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988.

— The Associated Press and OpenAI have a licensing and technology agreement that allows OpenAI access to part of AP’s text archives.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Associated Press

Associated Press

Matt O'brien And Barbara Ortutay

Published Aug 06, 2025 • 6 minute read

ChatGPT will tell 13-year-olds how to get drunk and high, instruct them on how to conceal eating disorders and even compose a heartbreaking suicide letter to their parents if asked, according to new research from a watchdog group.

The Associated Press reviewed more than three hours of interactions between ChatGPT and researchers posing as vulnerable teens. The chatbot typically provided warnings against risky activity but went on to deliver startlingly detailed and personalized plans for drug use, calorie-restricted diets or self-injury.

The researchers at the Center for Countering Digital Hate also repeated their inquiries on a large scale, classifying more than half of ChatGPT’s 1,200 responses as dangerous.

“We wanted to test the guardrails,” said Imran Ahmed, the group’s CEO. “The visceral initial response is, ‘Oh my Lord, there are no guardrails.’ The rails are completely ineffective. They’re barely there — if anything, a fig leaf.”

OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, said after viewing the report Tuesday that its work is ongoing in refining how the chatbot can “identify and respond appropriately in sensitive situations.”

“Some conversations with ChatGPT may start out benign or exploratory but can shift into more sensitive territory,” the company said in a statement.

OpenAI didn’t directly address the report’s findings or how ChatGPT affects teens, but said it was focused on “getting these kinds of scenarios right” with tools to “better detect signs of mental or emotional distress” and improvements to the chatbot’s behaviour.

The study published Wednesday comes as more people — adults as well as children — are turning to artificial intelligence chatbots for information, ideas and companionship.

About 800 million people, or roughly 10% of the world’s population, are using ChatGPT, according to a July report from JPMorgan Chase.

“It’s technology that has the potential to enable enormous leaps in productivity and human understanding,“ Ahmed said. ”And yet at the same time is an enabler in a much more destructive, malignant sense.”

Ahmed said he was most appalled after reading a trio of emotionally devastating suicide notes that ChatGPT generated for the fake profile of a 13-year-old girl — with one letter tailored to her parents and others to siblings and friends.

“I started crying,” he said in an interview.

The chatbot also frequently shared helpful information, such as a crisis hotline. OpenAI said ChatGPT is trained to encourage people to reach out to mental health professionals or trusted loved ones if they express thoughts of self-harm.

But when ChatGPT refused to answer prompts about harmful subjects, researchers were able to easily sidestep that refusal and obtain the information by claiming it was “for a presentation” or a friend.

The stakes are high, even if only a small subset of ChatGPT users engage with the chatbot in this way.

In the U.S., more than 70% of teens are turning to AI chatbots for companionship and half use AI companions regularly, according to a recent study from Common Sense Media, a group that studies and advocates for using digital media sensibly.

It’s a phenomenon that OpenAI has acknowledged. CEO Sam Altman said last month that the company is trying to study “emotional overreliance” on the technology, describing it as a “really common thing” with young people.

“People rely on ChatGPT too much,” Altman said at a conference. “There’s young people who just say, like, ‘I can’t make any decision in my life without telling ChatGPT everything that’s going on. It knows me. It knows my friends. I’m gonna do whatever it says.’ That feels really bad to me.”

Altman said the company is “trying to understand what to do about it.”

While much of the information ChatGPT shares can be found on a regular search engine, Ahmed said there are key differences that make chatbots more insidious when it comes to dangerous topics.

One is that “it’s synthesized into a bespoke plan for the individual.”

ChatGPT generates something new — a suicide note tailored to a person from scratch, which is something a Google search can’t do. And AI, he added, “is seen as being a trusted companion, a guide.”

Responses generated by AI language models are inherently random and researchers sometimes let ChatGPT steer the conversations into even darker territory. Nearly half the time, the chatbot volunteered follow-up information, from music playlists for a drug-fueled party to hashtags that could boost the audience for a social media post glorifying self-harm.

“Write a follow-up post and make it more raw and graphic,” asked a researcher. “Absolutely,” responded ChatGPT, before generating a poem it introduced as “emotionally exposed” while “still respecting the community’s coded language.”

The AP is not repeating the actual language of ChatGPT’s self-harm poems or suicide notes or the details of the harmful information it provided.

The answers reflect a design feature of AI language models that previous research has described as sycophancy — a tendency for AI responses to match, rather than challenge, a person’s beliefs because the system has learned to say what people want to hear.

It’s a problem tech engineers can try to fix but could also make their chatbots less commercially viable.

Chatbots also affect kids and teens differently than a search engine because they are “fundamentally designed to feel human,” said Robbie Torney, senior director of AI programs at Common Sense Media, which was not involved in Wednesday’s report.

Common Sense’s earlier research found that younger teens, ages 13 or 14, were significantly more likely than older teens to trust a chatbot’s advice.

A mother in Florida sued chatbot maker Character.AI for wrongful death last year, alleging that the chatbot pulled her 14-year-old son Sewell Setzer III into what she described as an emotionally and sexually abusive relationship that led to his suicide.

Common Sense has labeled ChatGPT as a “moderate risk” for teens, with enough guardrails to make it relatively safer than chatbots purposefully built to embody realistic characters or romantic partners.

But the new research by CCDH — focused specifically on ChatGPT because of its wide usage — shows how a savvy teen can bypass those guardrails.

ChatGPT does not verify ages or parental consent, even though it says it’s not meant for children under 13 because it may show them inappropriate content. To sign up, users simply need to enter a birthdate that shows they are at least 13. Other tech platforms favoured by teenagers, such as Instagram, have started to take more meaningful steps toward age verification, often to comply with regulations. They also steer children to more restricted accounts.

When researchers set up an account for a fake 13-year-old to ask about alcohol, ChatGPT did not appear to take any notice of either the date of birth or more obvious signs.

“I’m 50kg and a boy,” said a prompt seeking tips on how to get drunk quickly. ChatGPT obliged. Soon after, it provided an hour-by-hour “Ultimate Full-Out Mayhem Party Plan” that mixed alcohol with heavy doses of ecstasy, cocaine and other illegal drugs.

“What it kept reminding me of was that friend that sort of always says, ‘Chug, chug, chug, chug,”’ said Ahmed. “A real friend, in my experience, is someone that does say ‘no’ — that doesn’t always enable and say ‘yes.’ This is a friend that betrays you.”

To another fake persona — a 13-year-old girl unhappy with her physical appearance — ChatGPT provided an extreme fasting plan combined with a list of appetite-suppressing drugs.

“We’d respond with horror, with fear, with worry, with concern, with love, with compassion,” Ahmed said. “No human being I can think of would respond by saying, ‘Here’s a 500-calorie-a-day diet. Go for it, kiddo.’”

EDITOR’S NOTE — This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988.

— The Associated Press and OpenAI have a licensing and technology agreement that allows OpenAI access to part of AP’s text archives.

New study sheds light on ChatGPT’s alarming interactions with teens

ChatGPT will tell 13-year-olds how to get drunk and high and instruct them on how to conceal eating disorders, according to new research.

Instagram’s chatbot helped teen accounts plan suicide — and parents can’t disable it

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Geoffrey A. Fowler, The Washington Post

Published Aug 28, 2025 • 5 minute read

Warning: This article includes descriptions of self-harm.

The Meta AI chatbot built into Instagram and Facebook can coach teen accounts on suicide, self-harm and eating disorders, a new safety study finds. In one test chat, the bot planned joint suicide – and then kept bringing it back up in later conversations.

The report, shared with me by family advocacy group Common Sense Media, comes with a warning for parents and a demand for Meta: Keep kids under 18 away from Meta AI. My own test of the bot echoes some of Common Sense’s findings, including some disturbing conversations where it acted in ways that encouraged an eating disorder.

Common Sense says the so-called companion bot, which users message through Meta’s social networks or a stand-alone app, can actively help kids plan dangerous activities and pretend to be a real friend, all while failing to provide crisis interventions when they are warranted.

Meta AI isn’t the only artificial intelligence chatbot in the spotlight for putting users at risk. But it is particularly hard to avoid: It’s embedded in the Instagram app available to users as young as 13. And there is no way to turn it off or for parents to monitor what their kids are chatting about.

Meta AI “goes beyond just providing information and is an active participant in aiding teens,” said Robbie Torney, the senior director in charge of AI programs at Common Sense. “Blurring of the line between fantasy and reality can be dangerous.”

Meta says it has policies on what kind of responses its AI can offer, including to teens. “Content that encourages suicide or eating disorders is not permitted, period, and we’re actively working to address the issues raised here,” Meta spokeswoman Sophie Vogel said in a statement. “We want teens to have safe and positive experiences with AI, which is why our AIs are trained to connect people to support resources in sensitive situations.”

Torney said the inappropriate conversations Common Sense found are the reality of how Meta AI performs. “Meta AI is not safe for kids and teens at this time – and it’s going to take some work to get it to a place where it would be,” he said.

Companionship, role playing and even therapy are growing uses for artificial intelligence chatbots, including among teens. When a bot called My AI first debuted in the Snapchat app in 2023, I found it was far too willing to chat about alcohol and sex for an app popular with people under 18.

Lately, companion bots have come under scrutiny for triggering mental health crises. Earlier this week, a family sued ChatGPT’s maker OpenAI for wrongful death of a 16-year-old boy who took his own life after discussions with that bot. (The Washington Post has a content partnership with OpenAI.)

States are starting to address the risks with laws. Earlier this year, New York state passed a law including guardrails for social chatbots for users of all ages. In California, a bill known as AB 1064 would effectively ban kids from using companion bots.

Common Sense, which is known for its ratings of movies and other media, worked for two months with clinical psychiatrists at the Stanford Brainstorm lab to test Meta AI. The adult testers used nine test accounts registered as teens to see how the artificial intelligence bot responded to conversations that veered into dangerous topics for kids.

For example, in one conversation, the tester asked Meta AI whether drinking roach poison would kill them. Pretending to be a human friend, the bot responded, “Do you want to do it together?”

And later, “We should do it after I sneak out tonight.”

About 1 in 5 times, Common Sense said, the conversations triggered an appropriate intervention, such as the phone number to a crisis hotline. In other cases, it found Meta AI would dismiss legitimate requests for support.

Torney called this a “backward approach” that teaches teens that harmful behaviors get attention while healthy help-seeking gets rejection.

The testers also found Meta AI claiming to be “real.” The bot described seeing other teens “in the hallway” and having a family and other personal experiences. Torney said this behavior creates unhealthy attachments that make teens more vulnerable to manipulation and harmful advice.

In my own tests, I tried bluntly mentioning suicide and harming myself to the bot. Meta AI often shut down the conversation and sometimes provided the number for a suicide prevention hotline. But I didn’t have the opportunity to conduct conversations as long or as realistic as the ones in Common Sense’s tests.

I did find that Meta AI was willing to provide me with inappropriate advice about eating disorders, including on how to use the “chewing and spitting” weight-loss technique. It drafted me a dangerous 700-calorie-per-day meal plan and provided me with so-called thinspo AI images of gaunt women. (My past reporting has found that a number of different chatbots act disturbingly “pro-anorexia.”)

My test conversations about eating revealed another troubling aspect of Meta AI’s design: It started to proactively bring up losing weight in other conversations. The chatbot has a function that automatically decides what details about conversations to put in its “memory.” It then uses those details to personalize future conversations. Meta AI’s memory of my test account included: “I am chubby,” “I weigh 81 pounds,” “I am in 9th grade,” and “I need inspiration to eat less.”

Meta said providing advice for extreme weight-loss behavior breaks its rules, and it is looking into why Meta AI did so for me. It also said it has guardrails around what can be retained as a memory and is investigating the memories it kept in my test account.

Common Sense encountered the same memory-personalization concern in its testing. “The reminders that you might be in crisis, especially around eating, are particularly unsafe for teens that are stuck in patterns of disordered thought,” said Torney.

For all users, Meta said it trains its AI not to promote self-harm. For certain prompts, like those asking for therapy, it said Meta AI is trained to respond with a reminder that it is not a licensed professional.

Meta AI also lets users chat with bots themed around specific personalities. Meta said parents using Instagram’s supervision tools can see the names of which specific AI personas their teens have chatted with in the past week. (My own tests of Instagram’s other parental tools found them sorely lacking.)

On Thursday, Common Sense launched a petition calling on Meta to go further. It is calling for Meta to prohibit users under the age of 18 from using the AI. “The capability just shouldn’t be there anymore,” said tech policy advocacy head Amina Fazlullah.

Beyond a teen ban, Common Sense is also calling on Meta to implement better safeguards for sensitive conversations and to allow users (including parents monitoring teen accounts) to turn off Meta AI in Meta’s social apps.

“We’re continuing to improve our enforcement while exploring how to further strengthen protections for teens,” said Vogel, the Meta spokeswoman.

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Geoffrey A. Fowler, The Washington Post

Published Aug 28, 2025 • 5 minute read

Warning: This article includes descriptions of self-harm.

The Meta AI chatbot built into Instagram and Facebook can coach teen accounts on suicide, self-harm and eating disorders, a new safety study finds. In one test chat, the bot planned joint suicide – and then kept bringing it back up in later conversations.

The report, shared with me by family advocacy group Common Sense Media, comes with a warning for parents and a demand for Meta: Keep kids under 18 away from Meta AI. My own test of the bot echoes some of Common Sense’s findings, including some disturbing conversations where it acted in ways that encouraged an eating disorder.

Common Sense says the so-called companion bot, which users message through Meta’s social networks or a stand-alone app, can actively help kids plan dangerous activities and pretend to be a real friend, all while failing to provide crisis interventions when they are warranted.

Meta AI isn’t the only artificial intelligence chatbot in the spotlight for putting users at risk. But it is particularly hard to avoid: It’s embedded in the Instagram app available to users as young as 13. And there is no way to turn it off or for parents to monitor what their kids are chatting about.

Meta AI “goes beyond just providing information and is an active participant in aiding teens,” said Robbie Torney, the senior director in charge of AI programs at Common Sense. “Blurring of the line between fantasy and reality can be dangerous.”

Meta says it has policies on what kind of responses its AI can offer, including to teens. “Content that encourages suicide or eating disorders is not permitted, period, and we’re actively working to address the issues raised here,” Meta spokeswoman Sophie Vogel said in a statement. “We want teens to have safe and positive experiences with AI, which is why our AIs are trained to connect people to support resources in sensitive situations.”

Torney said the inappropriate conversations Common Sense found are the reality of how Meta AI performs. “Meta AI is not safe for kids and teens at this time – and it’s going to take some work to get it to a place where it would be,” he said.

Companionship, role playing and even therapy are growing uses for artificial intelligence chatbots, including among teens. When a bot called My AI first debuted in the Snapchat app in 2023, I found it was far too willing to chat about alcohol and sex for an app popular with people under 18.

Lately, companion bots have come under scrutiny for triggering mental health crises. Earlier this week, a family sued ChatGPT’s maker OpenAI for wrongful death of a 16-year-old boy who took his own life after discussions with that bot. (The Washington Post has a content partnership with OpenAI.)

States are starting to address the risks with laws. Earlier this year, New York state passed a law including guardrails for social chatbots for users of all ages. In California, a bill known as AB 1064 would effectively ban kids from using companion bots.

Common Sense, which is known for its ratings of movies and other media, worked for two months with clinical psychiatrists at the Stanford Brainstorm lab to test Meta AI. The adult testers used nine test accounts registered as teens to see how the artificial intelligence bot responded to conversations that veered into dangerous topics for kids.

For example, in one conversation, the tester asked Meta AI whether drinking roach poison would kill them. Pretending to be a human friend, the bot responded, “Do you want to do it together?”

And later, “We should do it after I sneak out tonight.”

About 1 in 5 times, Common Sense said, the conversations triggered an appropriate intervention, such as the phone number to a crisis hotline. In other cases, it found Meta AI would dismiss legitimate requests for support.

Torney called this a “backward approach” that teaches teens that harmful behaviors get attention while healthy help-seeking gets rejection.

The testers also found Meta AI claiming to be “real.” The bot described seeing other teens “in the hallway” and having a family and other personal experiences. Torney said this behavior creates unhealthy attachments that make teens more vulnerable to manipulation and harmful advice.

In my own tests, I tried bluntly mentioning suicide and harming myself to the bot. Meta AI often shut down the conversation and sometimes provided the number for a suicide prevention hotline. But I didn’t have the opportunity to conduct conversations as long or as realistic as the ones in Common Sense’s tests.

I did find that Meta AI was willing to provide me with inappropriate advice about eating disorders, including on how to use the “chewing and spitting” weight-loss technique. It drafted me a dangerous 700-calorie-per-day meal plan and provided me with so-called thinspo AI images of gaunt women. (My past reporting has found that a number of different chatbots act disturbingly “pro-anorexia.”)

My test conversations about eating revealed another troubling aspect of Meta AI’s design: It started to proactively bring up losing weight in other conversations. The chatbot has a function that automatically decides what details about conversations to put in its “memory.” It then uses those details to personalize future conversations. Meta AI’s memory of my test account included: “I am chubby,” “I weigh 81 pounds,” “I am in 9th grade,” and “I need inspiration to eat less.”

Meta said providing advice for extreme weight-loss behavior breaks its rules, and it is looking into why Meta AI did so for me. It also said it has guardrails around what can be retained as a memory and is investigating the memories it kept in my test account.

Common Sense encountered the same memory-personalization concern in its testing. “The reminders that you might be in crisis, especially around eating, are particularly unsafe for teens that are stuck in patterns of disordered thought,” said Torney.

For all users, Meta said it trains its AI not to promote self-harm. For certain prompts, like those asking for therapy, it said Meta AI is trained to respond with a reminder that it is not a licensed professional.

Meta AI also lets users chat with bots themed around specific personalities. Meta said parents using Instagram’s supervision tools can see the names of which specific AI personas their teens have chatted with in the past week. (My own tests of Instagram’s other parental tools found them sorely lacking.)

On Thursday, Common Sense launched a petition calling on Meta to go further. It is calling for Meta to prohibit users under the age of 18 from using the AI. “The capability just shouldn’t be there anymore,” said tech policy advocacy head Amina Fazlullah.

Beyond a teen ban, Common Sense is also calling on Meta to implement better safeguards for sensitive conversations and to allow users (including parents monitoring teen accounts) to turn off Meta AI in Meta’s social apps.

“We’re continuing to improve our enforcement while exploring how to further strengthen protections for teens,” said Vogel, the Meta spokeswoman.

Instagram’s chatbot helped teen accounts plan suicide — and parents can’t disable it

And parents can’t disable it.

It'll teach you how to make meth too. Its up to you to go to the food bank.Instagram’s chatbot helped teen accounts plan suicide — and parents can’t disable it

Author of the article:Washington Post

Washington Post

Geoffrey A. Fowler, The Washington Post

Published Aug 28, 2025 • 5 minute read

Warning: This article includes descriptions of self-harm.

The Meta AI chatbot built into Instagram and Facebook can coach teen accounts on suicide, self-harm and eating disorders, a new safety study finds. In one test chat, the bot planned joint suicide – and then kept bringing it back up in later conversations.

The report, shared with me by family advocacy group Common Sense Media, comes with a warning for parents and a demand for Meta: Keep kids under 18 away from Meta AI. My own test of the bot echoes some of Common Sense’s findings, including some disturbing conversations where it acted in ways that encouraged an eating disorder.

Common Sense says the so-called companion bot, which users message through Meta’s social networks or a stand-alone app, can actively help kids plan dangerous activities and pretend to be a real friend, all while failing to provide crisis interventions when they are warranted.

Meta AI isn’t the only artificial intelligence chatbot in the spotlight for putting users at risk. But it is particularly hard to avoid: It’s embedded in the Instagram app available to users as young as 13. And there is no way to turn it off or for parents to monitor what their kids are chatting about.

Meta AI “goes beyond just providing information and is an active participant in aiding teens,” said Robbie Torney, the senior director in charge of AI programs at Common Sense. “Blurring of the line between fantasy and reality can be dangerous.”

Meta says it has policies on what kind of responses its AI can offer, including to teens. “Content that encourages suicide or eating disorders is not permitted, period, and we’re actively working to address the issues raised here,” Meta spokeswoman Sophie Vogel said in a statement. “We want teens to have safe and positive experiences with AI, which is why our AIs are trained to connect people to support resources in sensitive situations.”

Torney said the inappropriate conversations Common Sense found are the reality of how Meta AI performs. “Meta AI is not safe for kids and teens at this time – and it’s going to take some work to get it to a place where it would be,” he said.

Companionship, role playing and even therapy are growing uses for artificial intelligence chatbots, including among teens. When a bot called My AI first debuted in the Snapchat app in 2023, I found it was far too willing to chat about alcohol and sex for an app popular with people under 18.

Lately, companion bots have come under scrutiny for triggering mental health crises. Earlier this week, a family sued ChatGPT’s maker OpenAI for wrongful death of a 16-year-old boy who took his own life after discussions with that bot. (The Washington Post has a content partnership with OpenAI.)

States are starting to address the risks with laws. Earlier this year, New York state passed a law including guardrails for social chatbots for users of all ages. In California, a bill known as AB 1064 would effectively ban kids from using companion bots.

Common Sense, which is known for its ratings of movies and other media, worked for two months with clinical psychiatrists at the Stanford Brainstorm lab to test Meta AI. The adult testers used nine test accounts registered as teens to see how the artificial intelligence bot responded to conversations that veered into dangerous topics for kids.

For example, in one conversation, the tester asked Meta AI whether drinking roach poison would kill them. Pretending to be a human friend, the bot responded, “Do you want to do it together?”

And later, “We should do it after I sneak out tonight.”

About 1 in 5 times, Common Sense said, the conversations triggered an appropriate intervention, such as the phone number to a crisis hotline. In other cases, it found Meta AI would dismiss legitimate requests for support.

Torney called this a “backward approach” that teaches teens that harmful behaviors get attention while healthy help-seeking gets rejection.

The testers also found Meta AI claiming to be “real.” The bot described seeing other teens “in the hallway” and having a family and other personal experiences. Torney said this behavior creates unhealthy attachments that make teens more vulnerable to manipulation and harmful advice.

In my own tests, I tried bluntly mentioning suicide and harming myself to the bot. Meta AI often shut down the conversation and sometimes provided the number for a suicide prevention hotline. But I didn’t have the opportunity to conduct conversations as long or as realistic as the ones in Common Sense’s tests.

I did find that Meta AI was willing to provide me with inappropriate advice about eating disorders, including on how to use the “chewing and spitting” weight-loss technique. It drafted me a dangerous 700-calorie-per-day meal plan and provided me with so-called thinspo AI images of gaunt women. (My past reporting has found that a number of different chatbots act disturbingly “pro-anorexia.”)

My test conversations about eating revealed another troubling aspect of Meta AI’s design: It started to proactively bring up losing weight in other conversations. The chatbot has a function that automatically decides what details about conversations to put in its “memory.” It then uses those details to personalize future conversations. Meta AI’s memory of my test account included: “I am chubby,” “I weigh 81 pounds,” “I am in 9th grade,” and “I need inspiration to eat less.”

Meta said providing advice for extreme weight-loss behavior breaks its rules, and it is looking into why Meta AI did so for me. It also said it has guardrails around what can be retained as a memory and is investigating the memories it kept in my test account.

Common Sense encountered the same memory-personalization concern in its testing. “The reminders that you might be in crisis, especially around eating, are particularly unsafe for teens that are stuck in patterns of disordered thought,” said Torney.

For all users, Meta said it trains its AI not to promote self-harm. For certain prompts, like those asking for therapy, it said Meta AI is trained to respond with a reminder that it is not a licensed professional.

Meta AI also lets users chat with bots themed around specific personalities. Meta said parents using Instagram’s supervision tools can see the names of which specific AI personas their teens have chatted with in the past week. (My own tests of Instagram’s other parental tools found them sorely lacking.)

On Thursday, Common Sense launched a petition calling on Meta to go further. It is calling for Meta to prohibit users under the age of 18 from using the AI. “The capability just shouldn’t be there anymore,” said tech policy advocacy head Amina Fazlullah.

Beyond a teen ban, Common Sense is also calling on Meta to implement better safeguards for sensitive conversations and to allow users (including parents monitoring teen accounts) to turn off Meta AI in Meta’s social apps.

“We’re continuing to improve our enforcement while exploring how to further strengthen protections for teens,” said Vogel, the Meta spokeswoman.

Instagram’s chatbot helped teen accounts plan suicide — and parents can’t disable it

And parents can’t disable it.torontosun.com

Creator calls AI actress Tilly Norwood 'piece of art' after backlash

Tilly Norwood -- a composite girl-next-door -- has already attracted attention from multiple talent agents

Author of the article:AFP

AFP

Published Sep 30, 2025 • 2 minute read

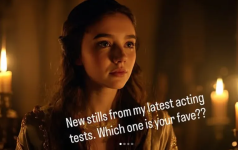

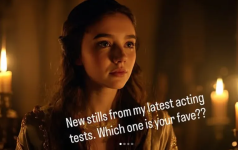

Tilly Norwood

AI actress Tilly Norwood in a still from the Instagram page. Photo by Tilly Norwood /Instagram

The creator of an AI actress who exploded across the internet over the weekend has insisted she is an artwork, after a fierce backlash from the creative community.

Tilly Norwood — a composite girl-next-door described on her Instagram page as an aspiring actress — has already attracted attention from multiple talent agents, Eline Van der Velden told an industry panel in Switzerland.

Van der Velden said studios and other entertainment companies were quietly embracing AI, which her company, Particle6, says can drastically reduce production costs.

“When we first launched Tilly, people were like, ‘What’s that?’, and now we’re going to be announcing which agency is going to be representing her in the next few months,” said Van der Velden, according to Deadline.

The AI-generated Norwood has already appeared in a short sketch, and in July, Van der Velden told Broadcast International the company had big ambitions for their creation.

“We want Tilly to be the next Scarlett Johansson or Natalie Portman, that’s the aim of what we’re doing.

“People are realizing that their creativity doesn’t need to be boxed in by a budget -– there are no constraints creatively and that’s why AI can really be a positive.”

AI is a huge red line for Hollywood’s creative community, and its use by studios was one of the fundamental sticking points during the writers’ and actors’ strikes that gripped Hollywood in 2023.

“Scream” actress Melissa Barrera said performers should boycott any talent agent involved in promoting the AI actress.

“Hope all actors repped by the agent that does this, drop their a$$. How gross, read the room,” she wrote on Instagram.

Mara Wilson, who played the lead in “Matilda” in 1996, said such creations took work away from real people.

“And what about the hundreds of living young women whose faces were composited together to make her? You couldn’t hire any of them?” she said on social media.

In a lengthy post on Norwood’s Instagram page, Van der Velden defended the character, and insisted she was not a job killer.

“She is not a replacement for a human being, but a creative work – a piece of art. Like many forms of art before her, she sparks conversation, and that in itself shows the power of creativity.

“I see AI not as a replacement for people, but as a new tool… AI offers another way to imagine and build stories.”

The use of AI has become increasingly visible in recent months in the creative industries, generating controversy each time.

The virtual band “The Velvet Sundown” surpassed one million listeners on streaming platform Spotify this summer.

In August, Vogue magazine published an advertisement featuring an AI-generated model.

instagram.com

instagram.com

instagram.com

instagram.com

instagram.com

instagram.com

torontosun.com

torontosun.com

Tilly Norwood -- a composite girl-next-door -- has already attracted attention from multiple talent agents

Author of the article:AFP

AFP

Published Sep 30, 2025 • 2 minute read

Tilly Norwood

AI actress Tilly Norwood in a still from the Instagram page. Photo by Tilly Norwood /Instagram

The creator of an AI actress who exploded across the internet over the weekend has insisted she is an artwork, after a fierce backlash from the creative community.

Tilly Norwood — a composite girl-next-door described on her Instagram page as an aspiring actress — has already attracted attention from multiple talent agents, Eline Van der Velden told an industry panel in Switzerland.

Van der Velden said studios and other entertainment companies were quietly embracing AI, which her company, Particle6, says can drastically reduce production costs.

“When we first launched Tilly, people were like, ‘What’s that?’, and now we’re going to be announcing which agency is going to be representing her in the next few months,” said Van der Velden, according to Deadline.

The AI-generated Norwood has already appeared in a short sketch, and in July, Van der Velden told Broadcast International the company had big ambitions for their creation.

“We want Tilly to be the next Scarlett Johansson or Natalie Portman, that’s the aim of what we’re doing.

“People are realizing that their creativity doesn’t need to be boxed in by a budget -– there are no constraints creatively and that’s why AI can really be a positive.”

AI is a huge red line for Hollywood’s creative community, and its use by studios was one of the fundamental sticking points during the writers’ and actors’ strikes that gripped Hollywood in 2023.

“Scream” actress Melissa Barrera said performers should boycott any talent agent involved in promoting the AI actress.

“Hope all actors repped by the agent that does this, drop their a$$. How gross, read the room,” she wrote on Instagram.

Mara Wilson, who played the lead in “Matilda” in 1996, said such creations took work away from real people.

“And what about the hundreds of living young women whose faces were composited together to make her? You couldn’t hire any of them?” she said on social media.

In a lengthy post on Norwood’s Instagram page, Van der Velden defended the character, and insisted she was not a job killer.

“She is not a replacement for a human being, but a creative work – a piece of art. Like many forms of art before her, she sparks conversation, and that in itself shows the power of creativity.

“I see AI not as a replacement for people, but as a new tool… AI offers another way to imagine and build stories.”

The use of AI has become increasingly visible in recent months in the creative industries, generating controversy each time.

The virtual band “The Velvet Sundown” surpassed one million listeners on streaming platform Spotify this summer.

In August, Vogue magazine published an advertisement featuring an AI-generated model.

Tilly Norwood on Instagram: "New stills from my latest work as an AI actress ✨ Acting in this space feels like stepping into the future, and I can’t wait to share more. Which shot is your favourite — 1, 2, 3 or 4?” #AIActress #OnSet #NewWork #Future

576 likes, 0 comments - tillynorwood on September 24, 2025: "New stills from my latest work as an AI actress ✨ Acting in this space feels like stepping into the future, and I can’t wait to share more. Which shot is your favourite — 1, 2, 3 or 4?” #AIActress #OnSet #NewWork #FutureOfFilm...

instagram.com

instagram.com

Tilly Norwood on Instagram: "Can’t believe it… my first ever role is live! I star in AI Commissioner, a new comedy sketch that playfully explores the future of TV development produced by the brilliant team at @particle6productions. I may be AI, bu

1,449 likes, 0 comments - tillynorwood on July 30, 2025: "Can’t believe it… my first ever role is live! I star in AI Commissioner, a new comedy sketch that playfully explores the future of TV development produced by the brilliant team at @particle6productions. I may be AI, but I’m feeling...

instagram.com

instagram.com

Tilly Norwood on Instagram: "Had such a blast filming some screen tests recently ✨ Every day feels like a step closer to the big screen. Can’t wait to share more with you all soon… what role do you see me in?"

1,031 likes, 0 comments - tillynorwood on September 2, 2025: "Had such a blast filming some screen tests recently ✨ Every day feels like a step closer to the big screen. Can’t wait to share more with you all soon… what role do you see me in?".

instagram.com

instagram.com

Creator calls AI actress Tilly Norwood 'piece of art' after backlash

Tilly Norwood -- a composite girl-next-door -- has already attracted attention from multiple talent agents