Many people say that the Englishman Charles Babbage invented the computer way back in 1837 - yes, 1837. Babbage's "Analytical Engine", built when Britain was the world's most technologically advanced nation, anticipated the first completed general-purpose computers by almost 100 years. Although never actually built, the machine was to be powered by steam (Georgian and Victorian Britain's equivalent of electricity) and would have been over 30 metres long and 10 metres wide. The input (programs and data) was to be provided to the machine via punched cards, a method being used at the time to direct mechanical looms. For output, the machine would have a printer, a curve plotter and a bell. The machine would also be able to punch numbers onto cards to be read in later. It employed ordinary base-10 fixed-point arithmetic.

There was to be a store (i.e., a memory) capable of holding 1,000 numbers of 50 digits each. An arithmetical unit (the "mill") would be able to perform all four arithmetic operations, plus comparisons and optionally square roots. But in many ways, this ingenious, but crude, machine cannot really be called a computer.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the British were in many wars at the forefront of computer and computer-related technology, much like the Japanese are today. It was the era that the British actually invented the computer.

The world's first proper computer was constructed at Manchester University. In 1948, Manchester University built 'Baby', the world's first computer. It was the first machine that had all the components now classically regarded as characteristic of the basic computer. Most importantly it was the first computer in the world that could store not only data but any (short!) user program in electronic memory and process it at electronic speed.

By 1949, the University (which today boasts 22 Nobel Laureates) built Manchester Mark 1, the first computer in the world to feature the ancestor of what we now know as a 'hard disc'.

Manchester University also built the Atlas computer in 1962.

It was possibly the world's very first supercomputer, and the fastest computer in the world until the release of the CDC 6600. It was said at the time that whenever it went offline half of the UK computer capacity was lost. It was a second-generation computer, using germanium transistors.

"Baby" may have been the world's first proper, FULL_SCALE computer (which has all the components now classically regarded as characteristic of the basic computer) but it wasn't the first.

The world's very first computer was "Colossus" (so-called because it took up at least one room). It was the world's first programmable digital computer and it started operating way back in 1944. It was invented by a man working for Britain's Post Office - Tommy Flowers. It was also ahead of American technology, which only had the comparable ENIAC fully working in 1946, by which time its design was obsolete.

It was used at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire to decipher German codes. Now this machine has been re-built and is set to crack codes once again...

Code-cracking WW2 computer restored for high-tech encryption race against modern machines

15th November 2007

Daily Mail

A code-cracking computer developed during the Second World War to intercept encrypted Nazi messages returns to action today.

Colossus, the world's first programmable digital computer, will begin the task of unravelling an encoded messages transmitted from Germany.

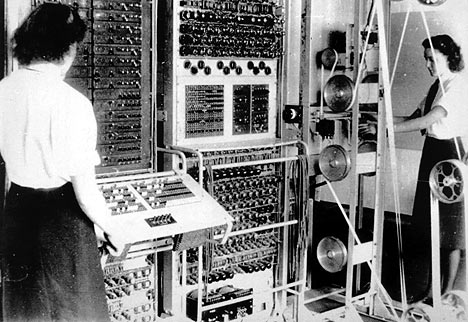

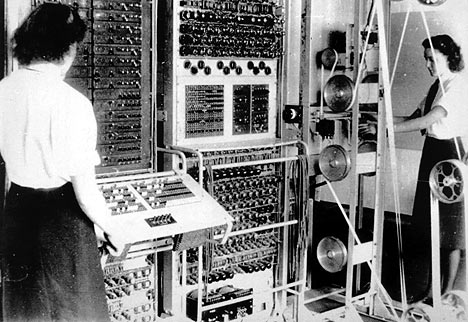

The world's first programmable digital computer: Colossus was created in the 1940s at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire

At 63 years old, the computer has been brought back to life

At the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the messages will be intercepted and then deciphered using Colossus, which was built in the 1940s.

To add to the pressure on old Colossus, a machine the size of a truck that took 14 years to rebuild, modern PC operators will be racing to see if they can unscramble the encoded transmissions first.

"It's going to be an interesting challenge, but I think we'll win," said Tony Sale, the engineer who led the project to reconstruct the computer, which along with many others was dismantled after the war to retain its secrecy.

War-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill credited those who built and operated Colossus at the Bletchley Park estate near London, including famed code-breaker Alan Turing, with helping to shorten World War Two by up to 18 months.

Tony Sale, the engineer who led the project to reconstruct Colussus, completes some last minute checks

Famed British code-breaker (and electronic computer pioneer) Alan Turing operated Colossus. Today, a machine is only called a computer if it is "Turing complete."

The Germans never fully worked out that their high-level encryption machine, called the Lorenz SZ42, had been cracked and continued to use it to encipher military commands, including crucial details on troop movements, ammunition and supplies.

Today's experiment is not just the culmination of a labour of love for Sale and his team, but an opportunity to show just how powerful and effective a 63-year-old computer can be and how avant-garde it was for its time.

The challenge will involve engineers at the Heinz Nixdorf Museum in Paderborn, Germany encoding three secret German texts using the Lorenz cipher and then transmitting them via radio.

At Bletchley, a team of experts will use World War Two era equipment to intercept the messages and transfer them to Sale to be loaded into the Colossus. The computer will then try to work out the cipher settings, allowing the messages to be read.

Just the transmission of the messages - 6,000 characters of German text in all - will take 20 minutes, while the deciphering could take anything from six hours to a day, although Sale hopes it will be at the shorter end of the range.

In its heyday, Colossus and several other computers like it were able to crack codes in a few hours, allowing Britain's war-time leaders to understand Germany's battle plans and adjust tactics accordingly.

Colossus is competing against modern-day computers in a race to see who can crack codes the fastest

Winston Churchill credited those who built the computer with shortening the war by 18 months

Even though the Colossi, as they were known, were dismantled after the war,

and their existence only properly discovered in the late 1970s when the Official Secrets Act provisions expired, they laid the groundwork for modern computing.

While their return to service will echo World War Two, the messages will bear no resemblance to secret war plans.

"There are sensitivities in Germany about such things, so we are just transmitting detailed descriptions of the Heinz Nixdorf Museum," said Sale.

Code-cracking computer shortened the war

•The Second World War was foreshortened by as much as several months and thousands of lives were saved by the invention of the Colossus code-cracking computer at Bletchley Park.

• By the end of the war, 63 million characters of high-grade German messages had been decrypted by the 550 people working on the Colossus machines at Bletchley Park.

• The machines, which began operating in 1944, were so fast that a mid-range modern PC programmed today to perform a similar code-breaking task would take as long as Colossus to achieve a result.

• Owing to the secrecy surrounding Colossus at the time, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the destruction of all the machines in 1945 following the Allied victory.

The Germans never fully worked out that their high-level encryption machine, the Lorenz SZ42, had been cracked by the British

• German teleprinter signals encrypted by Lorenz machines were first heard in Britain in 1940, by police officers on the south coast listening for possible spy transmissions.

• In August 1941, a procedural error by German operators enabled Brigadier John Tiltman, one of the top codebreakers at Bletchley Park, to work out the enciphering methods of the German Lorenz machine.

• In the early days messages still took four to six weeks to decrypt, by which time information could be stale and of little use.

• By December 1943, Tommy Flowers, a Post Office electronics engineer, had designed and built Colossus Mark I - the world's first practical electronic digital information processing machine and a forerunner of today's computers.

• The first Colossus machine arrived at Bletchley in December 1943 and used 1,500 thermionic valves (vacuum tubes).

• The Mark I began operating in January 1944, succeeded in June of that year by the Mark II. Ten Mark II machines were built.

• Lorenz codes had to be cracked by carrying out complex statistical analysis of the intercepted messages.

• Colossus could read paper tape at 5,000 characters per second and the paper tape in its wheels travelled at 30 miles per hour.

• The Lorenz machine was used exclusively for the most important messages passed between the German Army Field Marshals and their Central High Command in Berlin.

• Its size meant it was not a portable device like the Enigma machine which was also cracked at Bletchley Park.

• The rebuilt Colossus has been put together using eight photographs of the machine taken back in 1945 as well as circuit diagrams which were kept illegally by engineers who worked on the original project.

Colossus played its part in winning World War 2 by unravelling encoded messages transmitted by the Nazis

dailymail.co.uk

There was to be a store (i.e., a memory) capable of holding 1,000 numbers of 50 digits each. An arithmetical unit (the "mill") would be able to perform all four arithmetic operations, plus comparisons and optionally square roots. But in many ways, this ingenious, but crude, machine cannot really be called a computer.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the British were in many wars at the forefront of computer and computer-related technology, much like the Japanese are today. It was the era that the British actually invented the computer.

The world's first proper computer was constructed at Manchester University. In 1948, Manchester University built 'Baby', the world's first computer. It was the first machine that had all the components now classically regarded as characteristic of the basic computer. Most importantly it was the first computer in the world that could store not only data but any (short!) user program in electronic memory and process it at electronic speed.

By 1949, the University (which today boasts 22 Nobel Laureates) built Manchester Mark 1, the first computer in the world to feature the ancestor of what we now know as a 'hard disc'.

Manchester University also built the Atlas computer in 1962.

It was possibly the world's very first supercomputer, and the fastest computer in the world until the release of the CDC 6600. It was said at the time that whenever it went offline half of the UK computer capacity was lost. It was a second-generation computer, using germanium transistors.

"Baby" may have been the world's first proper, FULL_SCALE computer (which has all the components now classically regarded as characteristic of the basic computer) but it wasn't the first.

The world's very first computer was "Colossus" (so-called because it took up at least one room). It was the world's first programmable digital computer and it started operating way back in 1944. It was invented by a man working for Britain's Post Office - Tommy Flowers. It was also ahead of American technology, which only had the comparable ENIAC fully working in 1946, by which time its design was obsolete.

It was used at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire to decipher German codes. Now this machine has been re-built and is set to crack codes once again...

Code-cracking WW2 computer restored for high-tech encryption race against modern machines

15th November 2007

Daily Mail

A code-cracking computer developed during the Second World War to intercept encrypted Nazi messages returns to action today.

Colossus, the world's first programmable digital computer, will begin the task of unravelling an encoded messages transmitted from Germany.

The world's first programmable digital computer: Colossus was created in the 1940s at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire

At 63 years old, the computer has been brought back to life

At the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the messages will be intercepted and then deciphered using Colossus, which was built in the 1940s.

To add to the pressure on old Colossus, a machine the size of a truck that took 14 years to rebuild, modern PC operators will be racing to see if they can unscramble the encoded transmissions first.

"It's going to be an interesting challenge, but I think we'll win," said Tony Sale, the engineer who led the project to reconstruct the computer, which along with many others was dismantled after the war to retain its secrecy.

War-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill credited those who built and operated Colossus at the Bletchley Park estate near London, including famed code-breaker Alan Turing, with helping to shorten World War Two by up to 18 months.

Tony Sale, the engineer who led the project to reconstruct Colussus, completes some last minute checks

Famed British code-breaker (and electronic computer pioneer) Alan Turing operated Colossus. Today, a machine is only called a computer if it is "Turing complete."

The Germans never fully worked out that their high-level encryption machine, called the Lorenz SZ42, had been cracked and continued to use it to encipher military commands, including crucial details on troop movements, ammunition and supplies.

Today's experiment is not just the culmination of a labour of love for Sale and his team, but an opportunity to show just how powerful and effective a 63-year-old computer can be and how avant-garde it was for its time.

The challenge will involve engineers at the Heinz Nixdorf Museum in Paderborn, Germany encoding three secret German texts using the Lorenz cipher and then transmitting them via radio.

At Bletchley, a team of experts will use World War Two era equipment to intercept the messages and transfer them to Sale to be loaded into the Colossus. The computer will then try to work out the cipher settings, allowing the messages to be read.

Just the transmission of the messages - 6,000 characters of German text in all - will take 20 minutes, while the deciphering could take anything from six hours to a day, although Sale hopes it will be at the shorter end of the range.

In its heyday, Colossus and several other computers like it were able to crack codes in a few hours, allowing Britain's war-time leaders to understand Germany's battle plans and adjust tactics accordingly.

Colossus is competing against modern-day computers in a race to see who can crack codes the fastest

Winston Churchill credited those who built the computer with shortening the war by 18 months

Even though the Colossi, as they were known, were dismantled after the war,

and their existence only properly discovered in the late 1970s when the Official Secrets Act provisions expired, they laid the groundwork for modern computing.

While their return to service will echo World War Two, the messages will bear no resemblance to secret war plans.

"There are sensitivities in Germany about such things, so we are just transmitting detailed descriptions of the Heinz Nixdorf Museum," said Sale.

Code-cracking computer shortened the war

•The Second World War was foreshortened by as much as several months and thousands of lives were saved by the invention of the Colossus code-cracking computer at Bletchley Park.

• By the end of the war, 63 million characters of high-grade German messages had been decrypted by the 550 people working on the Colossus machines at Bletchley Park.

• The machines, which began operating in 1944, were so fast that a mid-range modern PC programmed today to perform a similar code-breaking task would take as long as Colossus to achieve a result.

• Owing to the secrecy surrounding Colossus at the time, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the destruction of all the machines in 1945 following the Allied victory.

The Germans never fully worked out that their high-level encryption machine, the Lorenz SZ42, had been cracked by the British

• German teleprinter signals encrypted by Lorenz machines were first heard in Britain in 1940, by police officers on the south coast listening for possible spy transmissions.

• In August 1941, a procedural error by German operators enabled Brigadier John Tiltman, one of the top codebreakers at Bletchley Park, to work out the enciphering methods of the German Lorenz machine.

• In the early days messages still took four to six weeks to decrypt, by which time information could be stale and of little use.

• By December 1943, Tommy Flowers, a Post Office electronics engineer, had designed and built Colossus Mark I - the world's first practical electronic digital information processing machine and a forerunner of today's computers.

• The first Colossus machine arrived at Bletchley in December 1943 and used 1,500 thermionic valves (vacuum tubes).

• The Mark I began operating in January 1944, succeeded in June of that year by the Mark II. Ten Mark II machines were built.

• Lorenz codes had to be cracked by carrying out complex statistical analysis of the intercepted messages.

• Colossus could read paper tape at 5,000 characters per second and the paper tape in its wheels travelled at 30 miles per hour.

• The Lorenz machine was used exclusively for the most important messages passed between the German Army Field Marshals and their Central High Command in Berlin.

• Its size meant it was not a portable device like the Enigma machine which was also cracked at Bletchley Park.

• The rebuilt Colossus has been put together using eight photographs of the machine taken back in 1945 as well as circuit diagrams which were kept illegally by engineers who worked on the original project.

Colossus played its part in winning World War 2 by unravelling encoded messages transmitted by the Nazis

dailymail.co.uk

Last edited: