William Tyndale was an English scholar who from 1525, became the first person to translate the Bible into English.

He was convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to common people.

Much of Tyndale's work eventually found its way into the King James Version (or "Authorised Version") of the Bible, published in 1611 during the reign of King James I.

But translating the Bible into English was a big "no-no" at that time.

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf (Thomas Cromwell was the Earl of Essex who was Henry VIII's chief minister from 1532 to 1540).

He "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned".

Tyndale's final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."

A hero for the information age

Dec 18th 2008

From The Economist print edition

Subversion, espionage and a man who gave his life to disseminate the Word

Getty Images

William Tyndale was burnt at the stake (after being strangled to death) in 1536 for translating the Bible into English

AN EMERGING nation looks increasingly confident as a player on the world stage, thanks to a mixture of commercial prowess and deft diplomacy. In its capital and in coastal cities, you can feel the excitement as small manufacturers, retailers and middlemen find new partners across the sea. But the country’s masters face a dilemma: the very technology, communications and knowhow that are boosting national fortunes also threaten to undermine the old power structure.

China in the 21st century, contemplating the pros and cons of the internet? No, Tudor England, at the time when a gifted, impulsive young man called William Tyndale arrived in London—not to make his fortune, but to transform the relationship between ordinary people and the written word. As he soon discovered, London in 1523 was a city where ideas as well as goods were being disseminated at a pace that frightened the authorities, triggering waves of book-burning and repression.

As a side effect of close commercial ties with northern Europe, England was being flooded with the writings of a renegade German monk called Martin Luther, who had openly defied the Pope and insisted on a new reading of the Bible which challenged some of the Catholic church’s long-established dogmas.

In some ways, Tyndale was poorly equipped to survive, let alone thrive, in this feverish atmosphere. He was no wheeler-dealer; more of an idealistic scholar whose linguistic gifts were so remarkable, and hence so subversive, that he was drawn into high religious politics.

His ruling passion was a simple one: he wanted to render the defining texts of his age and culture—the Old and New Testaments—in an accurate English translation which even “the boy that driveth the plough” could grasp. And the fact that he eventually fulfilled this aim, and paid for it with his life, should be acknowledged more frequently by anybody who cares about freedom of expression.

But for many of the bustling Londoners whom the young Tyndale met, questions of diplomacy, taxes and war were at least as pressing as those of theology or linguistics. King Henry VIII and his adviser Thomas Wolsey were trying to manoeuvre between two continental giants: the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, whose realms included Spain and (with varying degrees of real power) much of Teutonic middle Europe. Gamesmanship alone was unlikely to succeed unless the kingdom was willing to demonstrate its military power from time to time; so King Henry VIII imposed new taxes and started planning an ambitious programme of ship-building.

Harsh taxation was a source of much grumbling among the sort of friends that Tyndale began to make. Denied house-room by the bishop of London, he found accommodation with a member of London’s merchant class—the kind of man who was less interested in geopolitical games than in taking advantage of the new commercial relationships with the great business centres of northern Europe: Antwerp, Cologne and Hamburg.

In all these places, and in several other German cities, the art of printing books at a reasonable cost and in large numbers was more advanced than it was in England.

London, however, was well supplied with book-sellers, who were prepared to shop around the continent to find material for a growing body of literate customers. Thanks to commerce, and the increasing complexity of occupations such as ship-building, the number of English people who learned to read for purely practical as well as devotional reasons was growing.

Trade between England and the continent was facilitated by a German colony in London (living near the present-day site of Cannon Street railway station) and well-established groups of English businessmen in the commercial cities of Europe. And largely thanks to this network Tyndale was able to spend most of the final decade of his life dodging between one city and another, delivering bits of newly completed work to efficient presses whose output would duly cascade into England.

Tyndale has been described as one of the fathers of English literature. An exaggeration? No, the claim stands up. It is generally agreed that the founding texts of modern English are the plays of William Shakespeare and the Authorised or King James version of the Bible. Wasn’t the latter a team effort? In fact, that is only partially true. On investigation, we find one outstanding wordsmith whose prose decisively influenced the lovely cadences of the King James translation. But of course, he wasn’t around when it was published; Tyndale had been strangled, and then burned to death, in Belgium, 75 years earlier, crying out as he died, “may God open the eyes of the English king.”

Tyndale was ultimately more influential, and also in many ways a nobler figure than the more famous religious martyrs of the Tudor era, the Catholic Thomas More and the Protestant Thomas Cranmer. Both More and Cranmer served their time as enforcers of religious intolerance before falling victim to it themselves. No such stain sullies the record of Tyndale.

Tyndale was not a charming sophisticate like More. Like many a hyperactive genius, he seems to have lacked social grace, and was rather bad at reading the minds of people around him. The modern term for that is autistic; he would probably have found some neater way to describe a personality that is so absorbed with a rich inner world that it lacks the spare energy to decipher other people’s thoughts.

His life’s vision and dying supplication—for English people to have access to the Bible in their own language—came to pass (to use one of his own famous phrases) rather swiftly. A year after his death, a complete Bible—two-thirds of which had been translated by Tyndale, the rest by his associate Miles Coverdale—was published by royal permission. This electrified a nation where only a decade earlier, bishops had frantically tried to suppress copies of Tyndale’s subversive work. Six copies of the new translation were put on display in Old St Paul’s Church, and a spontaneous public reading of the entire text soon began. One man would stand at the lectern and proclaim the word until his voice gave out and a replacement stepped in. As a direct legacy of that heady moment, the Church of England is required by law to display a complete, accessible Bible in all its places of worship.

A candidate, then, for elevation as England’s national hero? Perhaps. But look more closely at Tyndale’s life, and it gets harder to present or understand him in purely national terms. In fact, what made Tyndale’s achievement possible was the burgeoning of international trade in goods, ideas and technology, as a counterweight to national tyranny.

How so? Consider the monarch whom Tyndale confronted. Just as Stalin eschewed world revolution in favour of “socialism in one country”, the project of Henry VIII—at least after his break with the Pope in 1530—could be described as “theocracy in one country”. In other words, an effort to establish total political and ideological control by blocking out foreign influence and crushing all rival centres of power at home. To do this, he was (like Stalin) prepared to use and then discard one trusted lieutenant, and one ideological slogan, after another.

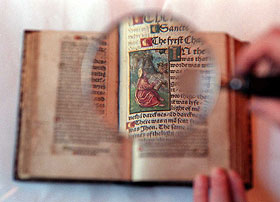

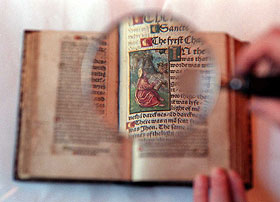

AFP

The Book for which Tyndale gave his life

That might sound shocking. Conventional English history sees Henry through a rose-tinted haze: a rambunctious old dog whose type-alpha personality had the happy effect of freeing England from the tyranny of papal authority. Remember, though, his purpose in throwing off Roman authority was not to usher in freedom, but to pave the way for an even more ruthless theocracy of his own.

It was a commonplace of the Soviet era that only people who were slightly abnormal, and utterly indifferent to their own comfort or survival, could find the courage to protest effectively against a totalitarian regime at the height of its powers. And Tyndale fits that description rather well. The main difference between his situation and that of the Soviet dissidents is that, fortunately, Henry’s England was much less successful in sealing off the realm from foreign ideas and influences.

When Tyndale went to Cambridge in 1517, the university was already bubbling with the new learning which had recently been introduced by the Dutch scholar Erasmus.

Among many other innovations, Erasmus had rejected the idea that study of the Bible should be confined to a Latin version produced in the year 400. As the Dutchman argued, the proper way to decipher that text was to go to the originals (Greek for New Testament, Hebrew for the Old) and parse them with the best available tools of linguistic science.

To the sharp-minded, polyglot Tyndale, all that was obvious, and he was pretty careless about where he expressed that opinion. As tutor to the family of a gentleman in Gloucestershire, he dismissed the Church’s claim to monopolise the reading and understanding of holy writ with a bluntness that startled the local clergy (even the ones who secretly agreed) and caused gossip in nearby alehouses; in other words, people said, he was siding with that German firebrand, Luther.

In the mercantile circles of London where Tyndale later found a home, people were excited not just by Luther’s ideas but also by the relative freedom enjoyed by Germany’s emerging statelets; the astonishing thing was not merely that Luther had protested, but also that he had actually survived the experience, and gone on to translate the Bible into German.

Thanks to the traders who had spirited Luther’s works, along with more conventional merchandise, through England’s ports, people in London learned what was going on in Germany with remarkable speed. And for exactly that reason, the climate in London was growing harsher.

Tyndale was helped, by Londoners with more worldly wisdom than himself, to go to Germany under a false name, with his half-completed rendering of the New Testament tucked deep inside his trunk. And from the moment he arrived in Hamburg, his life turned into a cat-and-mouse game of sneaking from one north European city to another, in search of rapid presses and nimble protectors.

Agents of the English king were fanning out all over the continent, meanwhile, there were plenty of people in the Teutonic lands (especially in the Low Countries where the Emperor was trying hard to enforce his writ) who did not want the Bible to be translated into English or any other modern language.

There was much tragicomedy in the contest between England’s thought police on one hand, and the evasive powers of Tyndale, or rather his canny Dutch, German and English friends, on the other. In 1525 the bishop of London recruited what he thought was a reliable agent in Antwerp, an Englishman called Augustine Packington, who promised to buy up all the copies of Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament that were rolling off the presses and pouring into England.

The “agent”—whose real sympathies lay with Tyndale—took the bishop’s money, bought lots of the offending books, and sent them to the bishop, who duly burned them in public. Imagine the bishop’s dismay when—as a contemporary account has it—a new and improved edition of Tyndale’s Testament began arriving “thick and threefold” in London. Tyndale had simply pocketed the bishop’s money and used it to finance a fresh version of his translation.

Faced with protests from the bishop, Packington used his wits to wriggle out of an awkward interrogation. “Surely, I bought all that were to be had, but I perceive that they have printed more since. I see that it will never be better as long as they have letters and stamps, wherefore you were best to buy the stamps too, and so you shall be sure.” Realising he had been outwitted, the bishop merely smiled.

The port of Antwerp, a power-house of international trade, served for a time as Tyndale’s safest refuge—but it was also the place where he met his downfall. In the end, his entrepreneurial friends’ cunning failed to protect him from the consequences of his own relative innocence.

Defending human dignity from tyranny can often mean sacrificing one's life

Tyndale had secured living quarters in the Antwerp home of an English merchant, Henry Pointz, who grew intensely protective of his brainy but unworldly lodger. But not protective enough, as it tragically turned out. A wealthy, mysterious Englishman named Henry Philips arrived in the port and rapidly gained Tyndale’s trust, and hence access to the Pointz household. Returning from a business trip, Pointz quickly came to suspect that the oily newcomer was a spy. But he failed to prevent his translator friend walking into a horrible trap. As he emerged from the Pointz family home; the tall Philips pointed down at the diminutive wordsmith who was duly marched off to jail.

A determined eurosceptic might argue that Tyndale’s capture and execution was the first, ghastly example of a pan-European arrest warrant, made possible by an early version of Europol and the Lisbon treaty. That is true, in a way: he was arrested after Henry VIII made known his feelings to the Holy Roman Emperor who was sovereign of the Low Countries.

But Henry’s motives were more personal than theological. He was infuriated by a pamphlet which denounced his moves to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Theology was moving in Tyndale’s direction by the time of his death.

England had half-switched to the Protestant cause, and Thomas Cromwell, the royal adviser, made a respectable stab at saving his compatriot’s life. However, having recently burned ten members of the ultra-Protestant Anabaptist movement, the regime of Henry VIII could hardly present itself as an advocate of religious freedom.

Jailed in the vast and forbidding fortress of Vilvoorde, Tyndale could easily have saved his life by agreeing with the Catholic hierarchy that the Bible was best left in Latin for the clergy to peruse. But he maintained his refusal in a way that impressed his Flemish jailers. “He had so preached to them who had him in charge…that they reported of him, that if he were not a good Christian man, they knew not whom they might take to be one.”

A hero for all nations, then? Whether in the land of his birth or the town of his death, Tyndale buffs are still regrettably thin on the ground, and it is hard to follow his trail. The atmosphere of medieval Antwerp can still be dimly apprehended in the foggy, cobbled streets and high gabled houses near the seafront; but nobody at the local tourist office has any idea where the “English House” was. As for Vilvoorde, the place of Tyndale’s death, just a handful of keen locals have worked passionately to investigate and commemorate the local martyr.

One of them is Wim Willems, a Protestant theology professor who divides his time between his Flemish homeland and central Africa.

“It’s when I go to Rwanda that Tyndale’s message really comes alive,” he explains.

“I tell my African students to think for themselves, to make own their own free and informed decisions about what is valid in their native, traditional cultures and in the cultural values of Europe, including the humanism that Tyndale personifies.”

And in Rwanda, more than in most parts of Europe, people can readily understand that defending human dignity from tyranny can often mean sacrificing one’s life.

Perhaps some of China’s dissidents should consider adopting him too.

economist.com

He was convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to common people.

Much of Tyndale's work eventually found its way into the King James Version (or "Authorised Version") of the Bible, published in 1611 during the reign of King James I.

But translating the Bible into English was a big "no-no" at that time.

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf (Thomas Cromwell was the Earl of Essex who was Henry VIII's chief minister from 1532 to 1540).

He "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned".

Tyndale's final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."

A hero for the information age

Dec 18th 2008

From The Economist print edition

Subversion, espionage and a man who gave his life to disseminate the Word

Getty Images

William Tyndale was burnt at the stake (after being strangled to death) in 1536 for translating the Bible into English

AN EMERGING nation looks increasingly confident as a player on the world stage, thanks to a mixture of commercial prowess and deft diplomacy. In its capital and in coastal cities, you can feel the excitement as small manufacturers, retailers and middlemen find new partners across the sea. But the country’s masters face a dilemma: the very technology, communications and knowhow that are boosting national fortunes also threaten to undermine the old power structure.

China in the 21st century, contemplating the pros and cons of the internet? No, Tudor England, at the time when a gifted, impulsive young man called William Tyndale arrived in London—not to make his fortune, but to transform the relationship between ordinary people and the written word. As he soon discovered, London in 1523 was a city where ideas as well as goods were being disseminated at a pace that frightened the authorities, triggering waves of book-burning and repression.

As a side effect of close commercial ties with northern Europe, England was being flooded with the writings of a renegade German monk called Martin Luther, who had openly defied the Pope and insisted on a new reading of the Bible which challenged some of the Catholic church’s long-established dogmas.

In some ways, Tyndale was poorly equipped to survive, let alone thrive, in this feverish atmosphere. He was no wheeler-dealer; more of an idealistic scholar whose linguistic gifts were so remarkable, and hence so subversive, that he was drawn into high religious politics.

His ruling passion was a simple one: he wanted to render the defining texts of his age and culture—the Old and New Testaments—in an accurate English translation which even “the boy that driveth the plough” could grasp. And the fact that he eventually fulfilled this aim, and paid for it with his life, should be acknowledged more frequently by anybody who cares about freedom of expression.

But for many of the bustling Londoners whom the young Tyndale met, questions of diplomacy, taxes and war were at least as pressing as those of theology or linguistics. King Henry VIII and his adviser Thomas Wolsey were trying to manoeuvre between two continental giants: the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, whose realms included Spain and (with varying degrees of real power) much of Teutonic middle Europe. Gamesmanship alone was unlikely to succeed unless the kingdom was willing to demonstrate its military power from time to time; so King Henry VIII imposed new taxes and started planning an ambitious programme of ship-building.

Harsh taxation was a source of much grumbling among the sort of friends that Tyndale began to make. Denied house-room by the bishop of London, he found accommodation with a member of London’s merchant class—the kind of man who was less interested in geopolitical games than in taking advantage of the new commercial relationships with the great business centres of northern Europe: Antwerp, Cologne and Hamburg.

In all these places, and in several other German cities, the art of printing books at a reasonable cost and in large numbers was more advanced than it was in England.

London, however, was well supplied with book-sellers, who were prepared to shop around the continent to find material for a growing body of literate customers. Thanks to commerce, and the increasing complexity of occupations such as ship-building, the number of English people who learned to read for purely practical as well as devotional reasons was growing.

Trade between England and the continent was facilitated by a German colony in London (living near the present-day site of Cannon Street railway station) and well-established groups of English businessmen in the commercial cities of Europe. And largely thanks to this network Tyndale was able to spend most of the final decade of his life dodging between one city and another, delivering bits of newly completed work to efficient presses whose output would duly cascade into England.

Tyndale has been described as one of the fathers of English literature. An exaggeration? No, the claim stands up. It is generally agreed that the founding texts of modern English are the plays of William Shakespeare and the Authorised or King James version of the Bible. Wasn’t the latter a team effort? In fact, that is only partially true. On investigation, we find one outstanding wordsmith whose prose decisively influenced the lovely cadences of the King James translation. But of course, he wasn’t around when it was published; Tyndale had been strangled, and then burned to death, in Belgium, 75 years earlier, crying out as he died, “may God open the eyes of the English king.”

Tyndale was ultimately more influential, and also in many ways a nobler figure than the more famous religious martyrs of the Tudor era, the Catholic Thomas More and the Protestant Thomas Cranmer. Both More and Cranmer served their time as enforcers of religious intolerance before falling victim to it themselves. No such stain sullies the record of Tyndale.

Tyndale was not a charming sophisticate like More. Like many a hyperactive genius, he seems to have lacked social grace, and was rather bad at reading the minds of people around him. The modern term for that is autistic; he would probably have found some neater way to describe a personality that is so absorbed with a rich inner world that it lacks the spare energy to decipher other people’s thoughts.

His life’s vision and dying supplication—for English people to have access to the Bible in their own language—came to pass (to use one of his own famous phrases) rather swiftly. A year after his death, a complete Bible—two-thirds of which had been translated by Tyndale, the rest by his associate Miles Coverdale—was published by royal permission. This electrified a nation where only a decade earlier, bishops had frantically tried to suppress copies of Tyndale’s subversive work. Six copies of the new translation were put on display in Old St Paul’s Church, and a spontaneous public reading of the entire text soon began. One man would stand at the lectern and proclaim the word until his voice gave out and a replacement stepped in. As a direct legacy of that heady moment, the Church of England is required by law to display a complete, accessible Bible in all its places of worship.

A candidate, then, for elevation as England’s national hero? Perhaps. But look more closely at Tyndale’s life, and it gets harder to present or understand him in purely national terms. In fact, what made Tyndale’s achievement possible was the burgeoning of international trade in goods, ideas and technology, as a counterweight to national tyranny.

How so? Consider the monarch whom Tyndale confronted. Just as Stalin eschewed world revolution in favour of “socialism in one country”, the project of Henry VIII—at least after his break with the Pope in 1530—could be described as “theocracy in one country”. In other words, an effort to establish total political and ideological control by blocking out foreign influence and crushing all rival centres of power at home. To do this, he was (like Stalin) prepared to use and then discard one trusted lieutenant, and one ideological slogan, after another.

AFP

The Book for which Tyndale gave his life

That might sound shocking. Conventional English history sees Henry through a rose-tinted haze: a rambunctious old dog whose type-alpha personality had the happy effect of freeing England from the tyranny of papal authority. Remember, though, his purpose in throwing off Roman authority was not to usher in freedom, but to pave the way for an even more ruthless theocracy of his own.

It was a commonplace of the Soviet era that only people who were slightly abnormal, and utterly indifferent to their own comfort or survival, could find the courage to protest effectively against a totalitarian regime at the height of its powers. And Tyndale fits that description rather well. The main difference between his situation and that of the Soviet dissidents is that, fortunately, Henry’s England was much less successful in sealing off the realm from foreign ideas and influences.

When Tyndale went to Cambridge in 1517, the university was already bubbling with the new learning which had recently been introduced by the Dutch scholar Erasmus.

Among many other innovations, Erasmus had rejected the idea that study of the Bible should be confined to a Latin version produced in the year 400. As the Dutchman argued, the proper way to decipher that text was to go to the originals (Greek for New Testament, Hebrew for the Old) and parse them with the best available tools of linguistic science.

To the sharp-minded, polyglot Tyndale, all that was obvious, and he was pretty careless about where he expressed that opinion. As tutor to the family of a gentleman in Gloucestershire, he dismissed the Church’s claim to monopolise the reading and understanding of holy writ with a bluntness that startled the local clergy (even the ones who secretly agreed) and caused gossip in nearby alehouses; in other words, people said, he was siding with that German firebrand, Luther.

In the mercantile circles of London where Tyndale later found a home, people were excited not just by Luther’s ideas but also by the relative freedom enjoyed by Germany’s emerging statelets; the astonishing thing was not merely that Luther had protested, but also that he had actually survived the experience, and gone on to translate the Bible into German.

Thanks to the traders who had spirited Luther’s works, along with more conventional merchandise, through England’s ports, people in London learned what was going on in Germany with remarkable speed. And for exactly that reason, the climate in London was growing harsher.

Tyndale was helped, by Londoners with more worldly wisdom than himself, to go to Germany under a false name, with his half-completed rendering of the New Testament tucked deep inside his trunk. And from the moment he arrived in Hamburg, his life turned into a cat-and-mouse game of sneaking from one north European city to another, in search of rapid presses and nimble protectors.

Agents of the English king were fanning out all over the continent, meanwhile, there were plenty of people in the Teutonic lands (especially in the Low Countries where the Emperor was trying hard to enforce his writ) who did not want the Bible to be translated into English or any other modern language.

There was much tragicomedy in the contest between England’s thought police on one hand, and the evasive powers of Tyndale, or rather his canny Dutch, German and English friends, on the other. In 1525 the bishop of London recruited what he thought was a reliable agent in Antwerp, an Englishman called Augustine Packington, who promised to buy up all the copies of Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament that were rolling off the presses and pouring into England.

The “agent”—whose real sympathies lay with Tyndale—took the bishop’s money, bought lots of the offending books, and sent them to the bishop, who duly burned them in public. Imagine the bishop’s dismay when—as a contemporary account has it—a new and improved edition of Tyndale’s Testament began arriving “thick and threefold” in London. Tyndale had simply pocketed the bishop’s money and used it to finance a fresh version of his translation.

Faced with protests from the bishop, Packington used his wits to wriggle out of an awkward interrogation. “Surely, I bought all that were to be had, but I perceive that they have printed more since. I see that it will never be better as long as they have letters and stamps, wherefore you were best to buy the stamps too, and so you shall be sure.” Realising he had been outwitted, the bishop merely smiled.

The port of Antwerp, a power-house of international trade, served for a time as Tyndale’s safest refuge—but it was also the place where he met his downfall. In the end, his entrepreneurial friends’ cunning failed to protect him from the consequences of his own relative innocence.

Defending human dignity from tyranny can often mean sacrificing one's life

Tyndale had secured living quarters in the Antwerp home of an English merchant, Henry Pointz, who grew intensely protective of his brainy but unworldly lodger. But not protective enough, as it tragically turned out. A wealthy, mysterious Englishman named Henry Philips arrived in the port and rapidly gained Tyndale’s trust, and hence access to the Pointz household. Returning from a business trip, Pointz quickly came to suspect that the oily newcomer was a spy. But he failed to prevent his translator friend walking into a horrible trap. As he emerged from the Pointz family home; the tall Philips pointed down at the diminutive wordsmith who was duly marched off to jail.

A determined eurosceptic might argue that Tyndale’s capture and execution was the first, ghastly example of a pan-European arrest warrant, made possible by an early version of Europol and the Lisbon treaty. That is true, in a way: he was arrested after Henry VIII made known his feelings to the Holy Roman Emperor who was sovereign of the Low Countries.

But Henry’s motives were more personal than theological. He was infuriated by a pamphlet which denounced his moves to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Theology was moving in Tyndale’s direction by the time of his death.

England had half-switched to the Protestant cause, and Thomas Cromwell, the royal adviser, made a respectable stab at saving his compatriot’s life. However, having recently burned ten members of the ultra-Protestant Anabaptist movement, the regime of Henry VIII could hardly present itself as an advocate of religious freedom.

Jailed in the vast and forbidding fortress of Vilvoorde, Tyndale could easily have saved his life by agreeing with the Catholic hierarchy that the Bible was best left in Latin for the clergy to peruse. But he maintained his refusal in a way that impressed his Flemish jailers. “He had so preached to them who had him in charge…that they reported of him, that if he were not a good Christian man, they knew not whom they might take to be one.”

A hero for all nations, then? Whether in the land of his birth or the town of his death, Tyndale buffs are still regrettably thin on the ground, and it is hard to follow his trail. The atmosphere of medieval Antwerp can still be dimly apprehended in the foggy, cobbled streets and high gabled houses near the seafront; but nobody at the local tourist office has any idea where the “English House” was. As for Vilvoorde, the place of Tyndale’s death, just a handful of keen locals have worked passionately to investigate and commemorate the local martyr.

One of them is Wim Willems, a Protestant theology professor who divides his time between his Flemish homeland and central Africa.

“It’s when I go to Rwanda that Tyndale’s message really comes alive,” he explains.

“I tell my African students to think for themselves, to make own their own free and informed decisions about what is valid in their native, traditional cultures and in the cultural values of Europe, including the humanism that Tyndale personifies.”

And in Rwanda, more than in most parts of Europe, people can readily understand that defending human dignity from tyranny can often mean sacrificing one’s life.

Perhaps some of China’s dissidents should consider adopting him too.

economist.com

Last edited: