A history set in stone

20/05/2007

The Telegraph

As an undergraduate, BBC TV presenter David Dimbleby was in too much of a hurry to appreciate the magnificent buildings around him.

Here, in the second of three extracts from his new book, and heralding his BBC series, he revisits some of England's grandest castles, halls and churches - and feels his spirits soar

I have a confession to make. I have a quirky hostility to William the Conqueror. His victory at Hastings rankles with me even though it was nearly a thousand years ago.

'Builders and architects are influenced by the look of buildings that they admire or want to emulate'

I cannot count the number of times I have tramped across that battlefield in snow and drizzle and summer heat. When I was seven I was sent to boarding school on Telham Hill, near Battle, in Sussex.

The school gave us a view across the country to the south. Battle Abbey, which stands just behind the spot where King Harold received the unwelcome arrow, was just out of sight to the west.

On wet days or Sundays when we could not play games we would be sent on a 'road' walk. These often took us down Powdermill Lane, which runs exactly between the Norman and Anglo-Saxon lines of the battle - between Telham and Senlac.

It was from Telham that William first caught sight of Harold's army marshalled opposite. I never thought of that day without sadness. Harold, exhausted after his long march from the north, and William, in my childish imagination, cockily invincible, trampling across our playing fields to steal our country from us.

King William I (aka William the Conqueror), King of England from 1066 to 1087

Within a few years of his victory in 1066, he had crushed all opposition and his supporters had taken over by conquest more than half the landholdings in the country. When people boast that their families 'came over with the Conqueror' I sometimes wonder whether they have any idea of the havoc they caused.

I live not far from Battle now, close to Pevensey Marshes, which in 1066 were still all sea. They were drained in the Middle Ages and are now criss-crossed by channels just wide enough to take a canoe. As you paddle gently along this flat water you can see in the distance, across the banks of sedge and the rough pasture where the cattle mooch, the outline of the crumbling ruins of Pevensey Castle.

Ruins of Pevensey Castle, East Sussex

Pevensey was built by the Romans in the third century as part of a chain of forts to protect the coastline. When William the Conqueror landed here 600 years later, he gave the remains of this castle to his half-brother with instructions to restore it. It was one of the first of many. Within two decades, 500 castles had been built to keep the English in submission.

Castles are an acquired taste, like battlefields. I once picnicked on a hillside above Marrakesh with Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, the commander of the Desert Army before Montgomery.

I was there to interview him about his life as a soldier. While the rest of the party drank wine and absorbed the scenery, the 'Auk' was working out his defensive strategy for the heights on which we sat: where he would deploy his guns, where the greatest danger lay.

It is the same with castles. For some people they come alive only when seen as military installations, with all their ingenious devices for protection from siege.

Never having been a soldier, I find this does not come naturally to me. One arrow slit seems much the same as any other.

Hedingham Castle, in Essex, is one of the most striking of Norman castles, with an austere and threatening appearance. I arrived there late on a hot summer's afternoon. It was an idyllic scene.

Hedingham Castle, Essex.

The thick walls of the castle, each stone immaculately cut to make perfect corners, still retained the heat of the day. In a similar way the building itself seemed to retain the imprint of its own history. It is one of the attractions of old buildings that they do not just look exciting but have the power to recreate the past for us.

In its heyday, the 1100s, the hall at Hedingham would have seen knights who were in thrall to the de Veres coming to do homage, and to discuss their problems, make their complaints and no doubt inform their lord about the political mood of the people on their land.

This hierarchical system was enforced by a strict code of etiquette. I have seen a court that was not unlike the court held by the de Veres. It was the court of bin Laden.

In the mid-1960s I was filming in Saudi Arabia, the first time the secretive house of Saud had allowed a television crew into their country. A few days before I was due to leave, I was invited to meet a building contractor who wanted to make a film record of his work in the Middle East and wondered whether I could help.

Early the next day I left Jeddah in a small plane, and we landed on a roadway high up in the hills at Taif, between Jeddah and Mecca. The contractor was none other than Osama bin Laden's father.

Osama, incidentally, was only 10 at the time, and not in evidence.

I was taken into a marquee where the sheik was holding court. The floor was covered with carpets.

Bin Laden himself was at one end, with what the de Veres would have recognised as his steward beside him.

Bin Laden being illiterate, all his deals were made verbally and recorded by this steward. I sat a few places away to his left, drinking tea and eating dates, waiting my turn.

Everyone in this huge tent, sitting cross-legged on the floor, was a supplicant of one kind or another.

Bin Laden sat in state, ordering his domain. I do not think a day at the court of the de Veres in the Middle Ages would have been much different.

Apart from the power of the monarch and his barons, the most powerful force in pre-Reformation Britain was the Church. Of all the land redistributed by William after the Norman Conquest, they received a third.

The monastery at Ely, founded in 673, sits in the middle of the Fen country, and held out against the Normans long after the rest of England had been subjugated. After the surrender of Ely, however, William the Conqueror appointed a new prior, a relation of his called Simeon, to take over the monastery.

Ely Cathedral in the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire. St Ethelreda, a Saxon princess, founded a religious community in Ely as early as 673 A.D. The present building dates from 1081 and was built by William the Conqueror.

Simeon set about an astonishing and typically Norman project: the building of a new church at Ely. He started the work, and in 1109 it was designated a cathedral, but it took a hundred years to complete.

It still dominates the horizon from miles around, and is romantically known as 'the Ship of the Fens'.

I have climbed to the top of the tower at Ely. I have taken off in a balloon at dawn and floated up past it. I have seen it from a punt on a far-away canal. The impression it makes is always the same: that quite apart from its great beauty, its fine skyline, its delicate carving, it is a statement of Norman power and domination as much as of religious devotion.

When you stand in the nave you do not need to be a believer to be thrilled by the scale of the building and by the harmony of its design, despite its use of different styles at different periods, as one technique for making an arch or a window succeeded another.

The cathedral is one of the longest in Britain, over 500 feet from end to end, and half of this is taken up by the nave. The nave is made up of three long arcades, or rows of arches, one above the other.

They are strongly built, with two firm legs to stand on and a rounded top, a design that is satisfying to look at because it is so simple and so old. Before builders worked out how to make a pointed arch, this was the standard way of bridging a gap to make doors and windows and support a roof.

The miracle of Norman building is that so much of it stood, and still stands. These days we build with the help of architects, surveyors and structural engineers. Then, there were just master masons evolving their techniques from experience, and passing on their knowledge from one generation to the next.

No tour in search of the origins of the building of Britain would be complete without a visit to the university city of Cambridge and to a building that must rank as one of the triumphs of the end of the Middle Ages: King's College Chapel.

King's College Chapel, Cambridgeshire

Henry VI, who had established Eton College near Windsor, laid the foundation stone of the chapel in 1446.

This building symbolises the yawning gulf between the attitudes of Norman times and the end of the medieval age. The minds of the people who built it had been set free, and what they built still sets us free. I sat on a bench, staring up at the great fan-vaulted ceiling.

King Henry VI founded Eton College and laid the foundation stone of the magnificent King's College Chapel

It is so delicately spun that it seems impossible it can stand. I fell into a trance, as though I was listening to fine music. Four hundred years separate this building from the arrival of the Normans with their mighty fortresses.

Henry VI was long dead by the time his chapel was complete; in later years it was enhanced by his successors.

Henry VII's heraldic beasts, dragons and greyhounds hold your eyes as you look east towards the high altar, and there, blocking the view, is the flamboyant oak organ loft given by Henry VIII. And always there is that ceiling.

I was led up a long winding stairway to the top of the chapel. A narrow door led to a dark chamber.

The floor was rough stone. The roof was held up by great wooden beams set at just the right height to give the unwary a mighty blow to the forehead as they pick their way along in the gloom.

This is the top of the fan-vaulted ceiling, the part the public never see. It was like standing on an eggshell. Only four inches thick, it weighs nearly 2,000 tonnes and stretches the full length of the chapel.

If you crawl on all fours you can find a number of holes cut through it, no more than half an inch across. I put my eye to one of them: it was like looking through a keyhole. I could just see the choir stalls far below and thought how tempting it would be to drop a stink bomb through the tiny gap during evensong.

Castles are an acquired taste, like battlefields

Those who believe that the true British character is buttoned up should look carefully at the response to Elizabeth I's funeral.

The tears came naturally, though perhaps Thomas Dekker, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, went a little over the top in describing the reaction as her funeral barge was rowed on the Thames to Whitehall in 1603: 'Fish under water wept out their eyes of pearl and swum blind after.'

Elizabeth I never built anything notable for herself. But by her patronage of those who supported her, flattered her and wanted to bask in the glory of a royal visit, she inspired some of the most lavish buildings Britain has ever seen.

Queen Elizabeth I's funeral procession, 1603

Her royal visits were on an unprecedented scale. She would arrive with a baggage train of 200 horses to transport her court and her servants. She might stay just a few days, or a week or two.

There are many examples of the lengths to which her courtiers would go to win her favour. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, spent £60,000 transforming his castle at Kenilworth to receive her.

When Dudley fell out of favour, the Queen flirted at a masque with her future Lord Chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton, and he became infatuated.

Desperate to receive a royal visit, Hatton built what was at the time the largest private house in England to welcome her: Holdenby, in Northamptonshire. With its two great courts, it was as large as the palace at Hampton Court, covering two acres. A village was moved to improve the view from the house.

No wonder Hatton was permanently short of money.

It is a sad story. Hatton refused to live at Holdenby until Elizabeth visited it - and she never came.

All that remains of Holdenby today are drawings of the house as it once was, one room incorporated into an 1870 restoration, part of the original columned doorway and two great arches, with the date 1583 inscribed on them, which once led into the lower court and now stand forlorn in a field, leading nowhere.

Although Holdenby has vanished, other great houses have survived to tell the story of England under Elizabeth.

Burghley, built by William Cecil near Stamford in Lincolnshire, is among the most magnificent. The best place from which to see Burghley is the roof.

Burghley, Lincolnshire

The view is spectacular. But it is the roof itself that makes the long climb worthwhile. For this is no ordinary roof. This looks more like a small town. Clusters of tall columns even give the impression of a Roman forum.

The columns themselves conceal chimneys - 76 in all, some hidden in the intricate balustrades that run round the roof. In Tudor times chimneys were an ostentatious display of wealth; count the chimneys and you can tell how many rooms a house contains.

It is a long journey from henry viii through the reign of Elizabeth I and the period of the Stuarts.

Those years saw some of the finest and most original buildings Britain has seen. They spoke of enterprise and daring, of fearless exploration, of a lively and imaginative interpretation of the universe.

Changes in building styles that spring from the way Britain has developed over centuries do not happen in strict chronological order, with one style neatly following another. On the contrary, things happen in a jumble.

Builders and architects are influenced by the look of buildings that they admire or that their patrons want to emulate. The start of the 18th century is a perfect example of this, and a handful of buildings at the centre of Oxford neatly encapsulate the trends.

As an undergraduate I must have walked past these great buildings hundreds of times without making the connection: like most students I was always in a hurry.

Going back to Oxford I realised how much I had missed, for within a few minutes' walk of each other is a group of buildings that tell the story of how Britain was changing from the 17th to the 18th century.

In a quadrangle is one of Britain's finest medieval interiors, the superbly vaulted medieval Divinity School, and leading from it the Convocation House. A great tower, the Tower of Five Orders, leads to the university's grandest library, the Bodleian.

The Tower of the Five Orders, Oxford, Oxfordshire. It is so named because it is ornamented with columns of each of the five orders of classical architecture - Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite - in ascending order. It leads to the Bodleian Library. It was here that Charles I summoned his parliament to meet during the Civil War, when 150 MPs and 80 peers abandoned Westminster to the Roundheads and set up shop in Oxford, hoping to sue for peace. Cromwell soon put an end to that.

This tower, built in 1610, is already feeding off classical Rome and Greece with a series of columns one above the other in different styles, including the three main orders of Greek building - Doric, Ionic and Corinthian - each with their easily identifiable tops or capitals: one plain, one with what looks like a partly opened scroll of paper, and one decorated with acanthus leaves.

The other two styles are Roman: the Tuscan and the Composite. The harmony of this courtyard, with its elegance, its lightness of touch and its pale golden stone, makes the spirits soar.

It was here that Charles I summoned his parliament to meet during the Civil War, when 150 MPs and 80 peers abandoned Westminster to the Roundheads and set up shop in Oxford, hoping to sue for peace. Cromwell soon put an end to that.

The first grand new building of Charles II's reign stands a hundred yards from the great quadrangle of the Divinity School. It was the work of the young Christopher Wren. In 1664, only 31 years old and with no formal schooling in building, he took on the design of the Sheldonian Theatre.

He could have chosen from any number of styles, but his interest and instinct led him to design a building on classical lines. He was an admirer of the work of Inigo Jones, whose career had come to a halt at the outbreak of the Civil War in the mid-17th century, and who had died when Wren was 20.

From the Sheldonian, Wren went on to build 53 churches in London as well as St Paul's Cathedral. His unmistakable churches in particular show how his style developed.

Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, was built by Sir Christopher Wren between 1664 and 1668

From any high point in the city of London you can spot several of them standing tall among acres of dull office blocks. Their spires are always distinctive, and that of St Bride's is still copied for wedding cakes.

Apart from St Paul's there is nothing pompous about Wren's designs, and nothing to intimidate either.

St Bride's church, Fleet Street, London. It could well be one of the most ancient, with worship perhaps dating back to the conversion of the Middle Saxons in the 7th century. It has been conjectured that, as the patron saint is Irish, the original building may have been founded by Celtic monks, missionaries proselytising the English. However, its latest incarnation was built around 1672 by Sir Christopher Wren. Due to its location on Fleet Street it has a long association with journalists and newspapers.

He is an architect of friendly, welcoming places that do not make you feel unworthy to enter.

Just opposite the Sheldonian Theatre, and built 50 years later, is an example of another interpretation of the classical approach. The Clarendon Building of 1711 is more strictly Palladian.

It was designed to house the University Press, but looks better suited to act as a bank or a library. Its architect, Nicholas Hawksmoor, had worked with Wren as a young man and later with another fashionable architect, John Vanbrugh.

Like the young Wren, Hawksmoor chose a design for the Clarendon that stemmed not from any continental travel but from the study of books about Roman architecture.

With its great columns running from ground to roof, supporting a triangular pediment, it is strong, solid and, if a building can be such a thing, supremely self-confident.

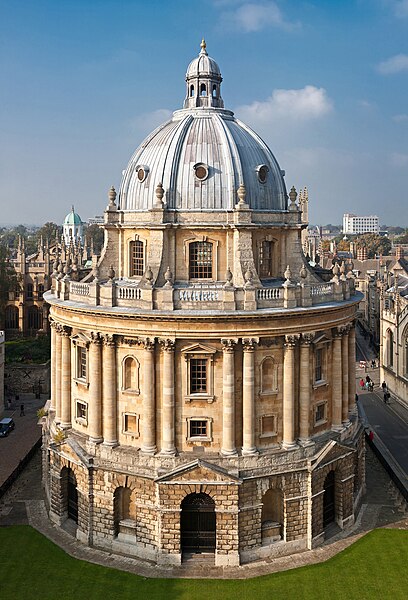

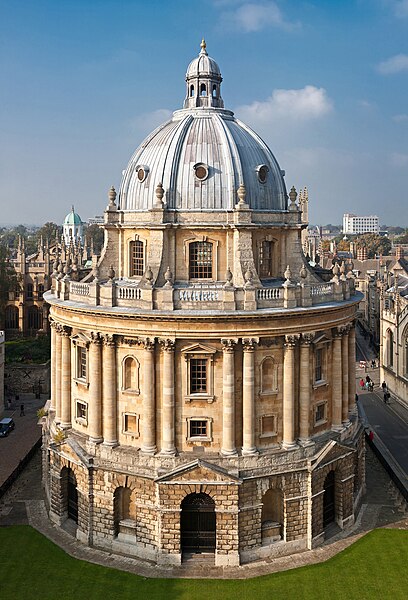

The last of the three examples that encapsulate the 18th-century approach to building is different. The Radcliffe Camera was built in the late 1730s.

Radcliffe Camera, Oxford

This was also originally designed by Hawksmoor, but on his death the job was taken on by James Gibbs, a Scottish architect. The Radcliffe is a great domed drum with columns in pairs all around the first floor.

It was built, and is still used, as a library. Its style is what experts call English baroque, a rather loose term. It is said to come from the Spanish word barrueco, an irregular-shaped pearl.

Whether true or not, it gives a good idea of what to expect from baroque, which is to expect the unexpected. Surprise, flamboyance and rich decoration are its hallmarks, but all reflecting classical design.

So, wandering around this small area in the middle of Oxford, you can see displayed all the trends of the new age: Wren's first flirtation with the classical, the baroque Radcliffe and, showing what would become the orthodoxy of the 18th century, the strictly Palladian Clarendon Building.

These three buildings illustrate how different interpretations of classical style overlapped. The architects who came later and who favoured a simpler approach to the classical turned their backs on what had gone before, the inventiveness and free spirit of Wren, Vanbrugh and Hawksmoor, in favour of a plainer, more austere style.

What better for the rational man than to build in a 'rational' style, according to rules in harmony with nature?

We are still addicted to the Georgian today, which blights many of our new developments. Some architects try to follow the Palladian rules, only to discover that modern building regulations for the dimensions of homes or requirements for under-floor computer ducting and air-conditioning can make it impossible to keep to the proper proportions.

The result could be called Disfigured Georgian, a sham that neither celebrates the past nor makes one particularly enamoured of the present.

Extracted from 'How We Built Britain' by David Dimbleby, © David Dimbleby 2007 (Bloomsbury, £20), published on 4 June, 2007. It is available for £18 plus £1.25 p&p from Telegraph Books on 0870 428 4115. The television series begins 3 June, 2007, at 9pm on BBC1.

telegraph.co.uk

20/05/2007

The Telegraph

As an undergraduate, BBC TV presenter David Dimbleby was in too much of a hurry to appreciate the magnificent buildings around him.

Here, in the second of three extracts from his new book, and heralding his BBC series, he revisits some of England's grandest castles, halls and churches - and feels his spirits soar

I have a confession to make. I have a quirky hostility to William the Conqueror. His victory at Hastings rankles with me even though it was nearly a thousand years ago.

'Builders and architects are influenced by the look of buildings that they admire or want to emulate'

I cannot count the number of times I have tramped across that battlefield in snow and drizzle and summer heat. When I was seven I was sent to boarding school on Telham Hill, near Battle, in Sussex.

The school gave us a view across the country to the south. Battle Abbey, which stands just behind the spot where King Harold received the unwelcome arrow, was just out of sight to the west.

On wet days or Sundays when we could not play games we would be sent on a 'road' walk. These often took us down Powdermill Lane, which runs exactly between the Norman and Anglo-Saxon lines of the battle - between Telham and Senlac.

It was from Telham that William first caught sight of Harold's army marshalled opposite. I never thought of that day without sadness. Harold, exhausted after his long march from the north, and William, in my childish imagination, cockily invincible, trampling across our playing fields to steal our country from us.

King William I (aka William the Conqueror), King of England from 1066 to 1087

Within a few years of his victory in 1066, he had crushed all opposition and his supporters had taken over by conquest more than half the landholdings in the country. When people boast that their families 'came over with the Conqueror' I sometimes wonder whether they have any idea of the havoc they caused.

I live not far from Battle now, close to Pevensey Marshes, which in 1066 were still all sea. They were drained in the Middle Ages and are now criss-crossed by channels just wide enough to take a canoe. As you paddle gently along this flat water you can see in the distance, across the banks of sedge and the rough pasture where the cattle mooch, the outline of the crumbling ruins of Pevensey Castle.

Ruins of Pevensey Castle, East Sussex

Pevensey was built by the Romans in the third century as part of a chain of forts to protect the coastline. When William the Conqueror landed here 600 years later, he gave the remains of this castle to his half-brother with instructions to restore it. It was one of the first of many. Within two decades, 500 castles had been built to keep the English in submission.

Castles are an acquired taste, like battlefields. I once picnicked on a hillside above Marrakesh with Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, the commander of the Desert Army before Montgomery.

I was there to interview him about his life as a soldier. While the rest of the party drank wine and absorbed the scenery, the 'Auk' was working out his defensive strategy for the heights on which we sat: where he would deploy his guns, where the greatest danger lay.

It is the same with castles. For some people they come alive only when seen as military installations, with all their ingenious devices for protection from siege.

Never having been a soldier, I find this does not come naturally to me. One arrow slit seems much the same as any other.

Hedingham Castle, in Essex, is one of the most striking of Norman castles, with an austere and threatening appearance. I arrived there late on a hot summer's afternoon. It was an idyllic scene.

Hedingham Castle, Essex.

The thick walls of the castle, each stone immaculately cut to make perfect corners, still retained the heat of the day. In a similar way the building itself seemed to retain the imprint of its own history. It is one of the attractions of old buildings that they do not just look exciting but have the power to recreate the past for us.

In its heyday, the 1100s, the hall at Hedingham would have seen knights who were in thrall to the de Veres coming to do homage, and to discuss their problems, make their complaints and no doubt inform their lord about the political mood of the people on their land.

This hierarchical system was enforced by a strict code of etiquette. I have seen a court that was not unlike the court held by the de Veres. It was the court of bin Laden.

In the mid-1960s I was filming in Saudi Arabia, the first time the secretive house of Saud had allowed a television crew into their country. A few days before I was due to leave, I was invited to meet a building contractor who wanted to make a film record of his work in the Middle East and wondered whether I could help.

Early the next day I left Jeddah in a small plane, and we landed on a roadway high up in the hills at Taif, between Jeddah and Mecca. The contractor was none other than Osama bin Laden's father.

Osama, incidentally, was only 10 at the time, and not in evidence.

I was taken into a marquee where the sheik was holding court. The floor was covered with carpets.

Bin Laden himself was at one end, with what the de Veres would have recognised as his steward beside him.

Bin Laden being illiterate, all his deals were made verbally and recorded by this steward. I sat a few places away to his left, drinking tea and eating dates, waiting my turn.

Everyone in this huge tent, sitting cross-legged on the floor, was a supplicant of one kind or another.

Bin Laden sat in state, ordering his domain. I do not think a day at the court of the de Veres in the Middle Ages would have been much different.

Apart from the power of the monarch and his barons, the most powerful force in pre-Reformation Britain was the Church. Of all the land redistributed by William after the Norman Conquest, they received a third.

The monastery at Ely, founded in 673, sits in the middle of the Fen country, and held out against the Normans long after the rest of England had been subjugated. After the surrender of Ely, however, William the Conqueror appointed a new prior, a relation of his called Simeon, to take over the monastery.

Ely Cathedral in the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire. St Ethelreda, a Saxon princess, founded a religious community in Ely as early as 673 A.D. The present building dates from 1081 and was built by William the Conqueror.

Simeon set about an astonishing and typically Norman project: the building of a new church at Ely. He started the work, and in 1109 it was designated a cathedral, but it took a hundred years to complete.

It still dominates the horizon from miles around, and is romantically known as 'the Ship of the Fens'.

I have climbed to the top of the tower at Ely. I have taken off in a balloon at dawn and floated up past it. I have seen it from a punt on a far-away canal. The impression it makes is always the same: that quite apart from its great beauty, its fine skyline, its delicate carving, it is a statement of Norman power and domination as much as of religious devotion.

When you stand in the nave you do not need to be a believer to be thrilled by the scale of the building and by the harmony of its design, despite its use of different styles at different periods, as one technique for making an arch or a window succeeded another.

The cathedral is one of the longest in Britain, over 500 feet from end to end, and half of this is taken up by the nave. The nave is made up of three long arcades, or rows of arches, one above the other.

They are strongly built, with two firm legs to stand on and a rounded top, a design that is satisfying to look at because it is so simple and so old. Before builders worked out how to make a pointed arch, this was the standard way of bridging a gap to make doors and windows and support a roof.

The miracle of Norman building is that so much of it stood, and still stands. These days we build with the help of architects, surveyors and structural engineers. Then, there were just master masons evolving their techniques from experience, and passing on their knowledge from one generation to the next.

No tour in search of the origins of the building of Britain would be complete without a visit to the university city of Cambridge and to a building that must rank as one of the triumphs of the end of the Middle Ages: King's College Chapel.

King's College Chapel, Cambridgeshire

Henry VI, who had established Eton College near Windsor, laid the foundation stone of the chapel in 1446.

This building symbolises the yawning gulf between the attitudes of Norman times and the end of the medieval age. The minds of the people who built it had been set free, and what they built still sets us free. I sat on a bench, staring up at the great fan-vaulted ceiling.

King Henry VI founded Eton College and laid the foundation stone of the magnificent King's College Chapel

It is so delicately spun that it seems impossible it can stand. I fell into a trance, as though I was listening to fine music. Four hundred years separate this building from the arrival of the Normans with their mighty fortresses.

Henry VI was long dead by the time his chapel was complete; in later years it was enhanced by his successors.

Henry VII's heraldic beasts, dragons and greyhounds hold your eyes as you look east towards the high altar, and there, blocking the view, is the flamboyant oak organ loft given by Henry VIII. And always there is that ceiling.

I was led up a long winding stairway to the top of the chapel. A narrow door led to a dark chamber.

The floor was rough stone. The roof was held up by great wooden beams set at just the right height to give the unwary a mighty blow to the forehead as they pick their way along in the gloom.

This is the top of the fan-vaulted ceiling, the part the public never see. It was like standing on an eggshell. Only four inches thick, it weighs nearly 2,000 tonnes and stretches the full length of the chapel.

If you crawl on all fours you can find a number of holes cut through it, no more than half an inch across. I put my eye to one of them: it was like looking through a keyhole. I could just see the choir stalls far below and thought how tempting it would be to drop a stink bomb through the tiny gap during evensong.

Castles are an acquired taste, like battlefields

Those who believe that the true British character is buttoned up should look carefully at the response to Elizabeth I's funeral.

The tears came naturally, though perhaps Thomas Dekker, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, went a little over the top in describing the reaction as her funeral barge was rowed on the Thames to Whitehall in 1603: 'Fish under water wept out their eyes of pearl and swum blind after.'

Elizabeth I never built anything notable for herself. But by her patronage of those who supported her, flattered her and wanted to bask in the glory of a royal visit, she inspired some of the most lavish buildings Britain has ever seen.

Queen Elizabeth I's funeral procession, 1603

Her royal visits were on an unprecedented scale. She would arrive with a baggage train of 200 horses to transport her court and her servants. She might stay just a few days, or a week or two.

There are many examples of the lengths to which her courtiers would go to win her favour. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, spent £60,000 transforming his castle at Kenilworth to receive her.

When Dudley fell out of favour, the Queen flirted at a masque with her future Lord Chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton, and he became infatuated.

Desperate to receive a royal visit, Hatton built what was at the time the largest private house in England to welcome her: Holdenby, in Northamptonshire. With its two great courts, it was as large as the palace at Hampton Court, covering two acres. A village was moved to improve the view from the house.

No wonder Hatton was permanently short of money.

It is a sad story. Hatton refused to live at Holdenby until Elizabeth visited it - and she never came.

All that remains of Holdenby today are drawings of the house as it once was, one room incorporated into an 1870 restoration, part of the original columned doorway and two great arches, with the date 1583 inscribed on them, which once led into the lower court and now stand forlorn in a field, leading nowhere.

Although Holdenby has vanished, other great houses have survived to tell the story of England under Elizabeth.

Burghley, built by William Cecil near Stamford in Lincolnshire, is among the most magnificent. The best place from which to see Burghley is the roof.

Burghley, Lincolnshire

The view is spectacular. But it is the roof itself that makes the long climb worthwhile. For this is no ordinary roof. This looks more like a small town. Clusters of tall columns even give the impression of a Roman forum.

The columns themselves conceal chimneys - 76 in all, some hidden in the intricate balustrades that run round the roof. In Tudor times chimneys were an ostentatious display of wealth; count the chimneys and you can tell how many rooms a house contains.

It is a long journey from henry viii through the reign of Elizabeth I and the period of the Stuarts.

Those years saw some of the finest and most original buildings Britain has seen. They spoke of enterprise and daring, of fearless exploration, of a lively and imaginative interpretation of the universe.

Changes in building styles that spring from the way Britain has developed over centuries do not happen in strict chronological order, with one style neatly following another. On the contrary, things happen in a jumble.

Builders and architects are influenced by the look of buildings that they admire or that their patrons want to emulate. The start of the 18th century is a perfect example of this, and a handful of buildings at the centre of Oxford neatly encapsulate the trends.

As an undergraduate I must have walked past these great buildings hundreds of times without making the connection: like most students I was always in a hurry.

Going back to Oxford I realised how much I had missed, for within a few minutes' walk of each other is a group of buildings that tell the story of how Britain was changing from the 17th to the 18th century.

In a quadrangle is one of Britain's finest medieval interiors, the superbly vaulted medieval Divinity School, and leading from it the Convocation House. A great tower, the Tower of Five Orders, leads to the university's grandest library, the Bodleian.

The Tower of the Five Orders, Oxford, Oxfordshire. It is so named because it is ornamented with columns of each of the five orders of classical architecture - Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite - in ascending order. It leads to the Bodleian Library. It was here that Charles I summoned his parliament to meet during the Civil War, when 150 MPs and 80 peers abandoned Westminster to the Roundheads and set up shop in Oxford, hoping to sue for peace. Cromwell soon put an end to that.

This tower, built in 1610, is already feeding off classical Rome and Greece with a series of columns one above the other in different styles, including the three main orders of Greek building - Doric, Ionic and Corinthian - each with their easily identifiable tops or capitals: one plain, one with what looks like a partly opened scroll of paper, and one decorated with acanthus leaves.

The other two styles are Roman: the Tuscan and the Composite. The harmony of this courtyard, with its elegance, its lightness of touch and its pale golden stone, makes the spirits soar.

It was here that Charles I summoned his parliament to meet during the Civil War, when 150 MPs and 80 peers abandoned Westminster to the Roundheads and set up shop in Oxford, hoping to sue for peace. Cromwell soon put an end to that.

The first grand new building of Charles II's reign stands a hundred yards from the great quadrangle of the Divinity School. It was the work of the young Christopher Wren. In 1664, only 31 years old and with no formal schooling in building, he took on the design of the Sheldonian Theatre.

He could have chosen from any number of styles, but his interest and instinct led him to design a building on classical lines. He was an admirer of the work of Inigo Jones, whose career had come to a halt at the outbreak of the Civil War in the mid-17th century, and who had died when Wren was 20.

From the Sheldonian, Wren went on to build 53 churches in London as well as St Paul's Cathedral. His unmistakable churches in particular show how his style developed.

Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, was built by Sir Christopher Wren between 1664 and 1668

From any high point in the city of London you can spot several of them standing tall among acres of dull office blocks. Their spires are always distinctive, and that of St Bride's is still copied for wedding cakes.

Apart from St Paul's there is nothing pompous about Wren's designs, and nothing to intimidate either.

St Bride's church, Fleet Street, London. It could well be one of the most ancient, with worship perhaps dating back to the conversion of the Middle Saxons in the 7th century. It has been conjectured that, as the patron saint is Irish, the original building may have been founded by Celtic monks, missionaries proselytising the English. However, its latest incarnation was built around 1672 by Sir Christopher Wren. Due to its location on Fleet Street it has a long association with journalists and newspapers.

He is an architect of friendly, welcoming places that do not make you feel unworthy to enter.

Just opposite the Sheldonian Theatre, and built 50 years later, is an example of another interpretation of the classical approach. The Clarendon Building of 1711 is more strictly Palladian.

It was designed to house the University Press, but looks better suited to act as a bank or a library. Its architect, Nicholas Hawksmoor, had worked with Wren as a young man and later with another fashionable architect, John Vanbrugh.

Like the young Wren, Hawksmoor chose a design for the Clarendon that stemmed not from any continental travel but from the study of books about Roman architecture.

With its great columns running from ground to roof, supporting a triangular pediment, it is strong, solid and, if a building can be such a thing, supremely self-confident.

The last of the three examples that encapsulate the 18th-century approach to building is different. The Radcliffe Camera was built in the late 1730s.

Radcliffe Camera, Oxford

This was also originally designed by Hawksmoor, but on his death the job was taken on by James Gibbs, a Scottish architect. The Radcliffe is a great domed drum with columns in pairs all around the first floor.

It was built, and is still used, as a library. Its style is what experts call English baroque, a rather loose term. It is said to come from the Spanish word barrueco, an irregular-shaped pearl.

Whether true or not, it gives a good idea of what to expect from baroque, which is to expect the unexpected. Surprise, flamboyance and rich decoration are its hallmarks, but all reflecting classical design.

So, wandering around this small area in the middle of Oxford, you can see displayed all the trends of the new age: Wren's first flirtation with the classical, the baroque Radcliffe and, showing what would become the orthodoxy of the 18th century, the strictly Palladian Clarendon Building.

These three buildings illustrate how different interpretations of classical style overlapped. The architects who came later and who favoured a simpler approach to the classical turned their backs on what had gone before, the inventiveness and free spirit of Wren, Vanbrugh and Hawksmoor, in favour of a plainer, more austere style.

What better for the rational man than to build in a 'rational' style, according to rules in harmony with nature?

We are still addicted to the Georgian today, which blights many of our new developments. Some architects try to follow the Palladian rules, only to discover that modern building regulations for the dimensions of homes or requirements for under-floor computer ducting and air-conditioning can make it impossible to keep to the proper proportions.

The result could be called Disfigured Georgian, a sham that neither celebrates the past nor makes one particularly enamoured of the present.

Extracted from 'How We Built Britain' by David Dimbleby, © David Dimbleby 2007 (Bloomsbury, £20), published on 4 June, 2007. It is available for £18 plus £1.25 p&p from Telegraph Books on 0870 428 4115. The television series begins 3 June, 2007, at 9pm on BBC1.

telegraph.co.uk

Last edited: