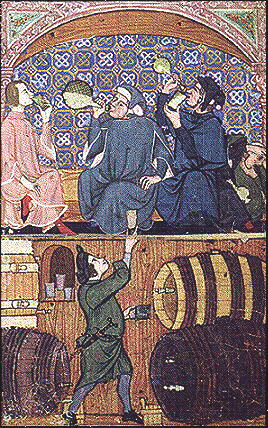

Inns appeared in England in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and were apparently fairly common, especially in towns, by the fifteenth century. The earliest buildings still standing today, such as New Inn, Gloucester, or King's Head, Aylesbury, date from this time. While inns provided lodgings for travelers, taverns were drinking houses seeking to cater for the more prosperous levels of society. The leading taverners in larger towns were themselves vintners or acted as agents for vintners. The Vintner's Company of London, for instance, secured an essential monopoly of the retail trade in the city in 1364. A tavern of the later Medieval period might be imagined as a fairly substantial building of several rooms and a generous cellar. Taverns had signs to advertise their presence to potential customers, and branches and leaves would be hung over the door to give notice that wine could be purchased. Some taverns sold wine as their only beverage, and a customer could also purchase food brought in from a convenient cook-shop. Taverns seldom offered lodgings or very elaborate feasting, such as would be expected at inns. Pastimes like gambling, singing, and seeking prostitutes were a more common part of the tavern scene.

[SIZE=-1]Excerpt from: Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England by Compton Reeves. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.[/SIZE]

The favorite adult recreation of the villagers was undoubtedly drinking. Both men and women gathered in the "tavern," usually meaning the house of a neighbor who had recently brewed a batch of ale, cheap at the established price of three gallons for a penny. There they passed the evening like modern villagers visiting the local pub. Accidents, quarrels, and acts of violence sometimes followed a session of drinking, in the thirteenth century as well as subsequent ones. Some misadventures may be deduced from the terse manorial court records. The rolls of the royal coroners, reporting fatal accidents, spell out many in graphic detail: In 1276 in Elstow, Osbert le Wuayl, son of William Cristmasse, coming home at about midnight "Drunk and dis gustingly over-fed," after an evening in Bedford, fell and struck his head fatally on a stone "breaking the whole of his head." One man stumbled off his horse riding home from the tavern; another fell into a well in the marketplace and drowned; a third, relieving himself in a pond, fell in; still another, carrying a pot of ale down the village street, was bitten by a dog, tripped while picking up a stone to throw, and struck his head against a wall; a child slipped from her drunken mother's lap into a pan of hot milk on the hearth.

One village craft was so widely practiced that it hardly belonged to craftsmen. Every village not only had its brewers, but had them all up and down the street. Many if not most of them were women. Ale was as necessary to life in an English medieval village as bread, but where flour-grinding and bread-baking were strictly guarded seigneurial monopolies, brewing was everywhere freely permitted and freely practiced. How the lords came to overlook this active branch of industry is a mystery (though they found a way to profit from it by fining the brewers for weak ale or faulty measure). Not only barley (etymologically related to beer) but oats and wheat were used, along with malt, as principal ingredients. The procedure was to make a batch of ale, display a sign, and turn one's house into a temporary tavern. Some equipment was needed, principally a large cauldron, but this did not prevent poor women from brewing. All twenty-three persons indicted by Elton village ale tasters in 1279 were WOMEN. Seven were pardoned because they were poor.

Excerpts from: Life in a Medieval Village by Frances & Joseph Gies. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990.

http://www.godecookery.com/mtales/mtales13.htm