They are often described as ruthless and bloodthirsty, famous for their tyrannical reigns of terror. Here are right of the bloodiest emperors of Ancient Rome...

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors in history

They are often described as ruthless and bloodthirsty, famous for their tyrannical reigns of terror. Here, historian Sean Lang examines eight of the bloodiest emperors of Ancient Rome…

Monday 18th July 2016

Sean Lang

BBC History Magazine

We all know about the Roman Emperors, don't we? Mad, bad and decidedly dangerous to know. Who can forget Peter Ustinov's Nero in the 1951 epic Quo Vadis?, or John Hurt's tortured and murderous Caligula in the BBC's I, Claudius?

In fact, as historians point out (to anyone who will listen), many of the emperors on the list below were competent – even gifted – administrators, and the sources for some of the more lurid stories about them are not always above suspicion of exaggeration or invention. And some of the crimes that most shocked their contemporaries, like a penchant for performing in public, would not necessarily offend us so much today.

Some emperors, like Nero or Domitian, have passed into history as models of erratic, paranoid tyrants; others, like Diocletian, were able administrators, providing good government (unlessyou happened to be a Christian, in which case you were in great peril). Even under the worst emperors Rome continued to function, but involvement in public life could become a decidedly dangerous business.

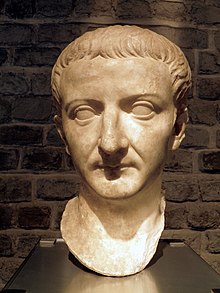

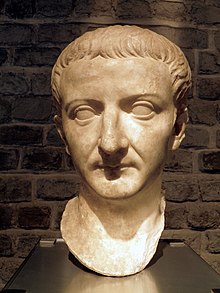

Tiberius (ruled AD 14–37)

Tiberius was the successor to Augustus, though Augustus did not particularly want Tiberius to succeed him, and it was only the untimely death of the emperor's grandsons Gaius and Lucius, and Augustus's decision to exile their younger brother, Agrippa Postumus, that put Tiberius in line for the imperial throne.

Tiberius was a gifted military commander and respected the authority of the senate. However, he had a gloomy and increasingly suspicious outlook that won him few friends and led him into a bitter dispute with Agrippina, the widow of his war hero nephew Germanicus. Fatally, Tiberius relied heavily on the ambitious and ruthless Aelius Sejanus, who instituted a reign of terror until Tiberius, learning that Sejanus planned to seize power himself, had him arrested and executed.

Tiberius sank into morbid suspicion of everyone around him: he retreated to the island of Capri and revived the ancient accusation of maiestas (treason) and used it to sentence to death anyone he suspected. Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus give us a picture of Tiberius living on Capri as a depraved sexual predator, which may owe more to colourful imagination than to fact, though he certainly made use of a sheer drop into the sea to dispose of anyone he took issue with. Tiberius was not a monster in the mould of some of his successors, but he certainly set the tone for what was to come.

Gaius (Caligula) (ruled AD 37–41)

Gaius (‘Caligula, or ‘little bootee’ – a childhood nickname given him by his father's troops) is best known for a series of eccentric actions, such as declaring war on the sea and proclaiming himself a god.

His reign actually began quite promisingly, but after a serious bout of illness he developed paranoia that led him into alarmingly erratic behaviour, possibly including incest with his sister, Julia Drusilla, whom he named as his heir.

Gaius took particular delight in humiliating the senate, claiming that he could make anyone consul, even his horse (though, contrary to the popular story, he didn't actually go through with this). As the son of Germanicus [a prominent general], Gaius was keen to establish his military credentials, though his campaign in Germany achieved little and his abortive invasion of Britain had to be turned into a battle with the sea god Neptune: he is said to have told his troops to attack the waves with their swords and gather seashells as booty.

Gaius declared himself a god and used his divine status to establish what was, in effect, an absolutist monarchy in Rome. He followed Tiberius's example of using treason trials to eliminate enemies, real or imagined. In the end it was his rather childish taunting of Cassius Chaerea, a member of the Praetorian guard, which brought Gaius down. Chaerea arranged for his assassination at the Palatine Games. He is supposed to have protested that he couldn't be killed because he was an immortal god, but he turned out to be rather less immortal than he thought.

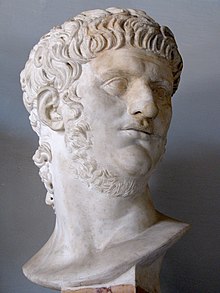

Nero (ruled AD 54–68 )

Nero is the Roman Emperor we all love to hate, and not without reason. He was actually a competent administrator, and he was aided by some very able men, including his tutor – the writer Seneca. However, he was also unquestionably a murderer, starting with his step-brother Britannicus, with whom he had been supposed to share power, and progressing through his wife Octavia, whom he deserted for his lover, Poppeaea, and then had executed on a trumped-up charge of adultery.

Probably on Poppaea's prompting he had his own mother murdered, though the initial attempt, using a collapsible boat, went wrong, and she had to be beaten to death instead. He then kicked Poppaea to death in a fit of anger while she was pregnant with his child.

Contrary to the myth, Nero did not start the great fire of Rome, nor did he ‘fiddle’ (nor even play the lyre), while the city burned – in fact, he organised relief work for its victims and planned the rebuilding. But Nero’s fondness for his own music and poetry, which made him force senators to sit through his own interminable and talentless recitals, meant people could easily believe it of him.

Nero was much hated for building his huge, tasteless ‘golden house’ complex [aka the Domus Aurea, a large landscaped portico villa] in the ruins of what had been the public area of central Rome. He undoubtedly persecuted Christians in large numbers, and his childish insistence on winning the laurels at the Olympic Games in Greece – whether or not he actually won, or indeed finished the race – brought the whole empire into disrepute.

Nero was toppled by an army revolt that sunk into a destructive three-way civil war.

Domitian (ruled AD 81–96)

Domitian was the younger son of Vespasian, the general who had emerged from the chaos after Nero's fall and restored a certain element of stability and normality to Roman public life.

Domitian inherited none of his father's charm and, like others on this list, he suffered from deep suspicion of those around him, amounting to paranoia, possibly a result of his narrow escape from being killed during the civil war. He was particularly suspicious of the senate and had a number of leading citizens executed for conspiracy against him, including 12 ex-consuls and two of his own cousins.

Domitian’s rule became steadily more autocratic, and he demanded to be treated like a god. He turned against philosophers, sending many of them into exile, and he arranged the judicial murder of the chief vestal virgin, having her buried alive in a specially constructed tomb.

Domitian was eventually brought down by a conspiracy arranged by his wife, Domitia, and was somewhat inexpertly stabbed by a palace servant. Some historians think Domitian's tyranny has been overstated; others have compared him to Saddam Hussein at his most vengeful.

Commodus (ruled AD 180–192)

Commodus was the emperor immortalised by Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000). Commodus was indeed a passionate follower of gladiatorial combat, and himself fought in the arena, sometimes dressed as Hercules, for which he awarded himself divine honours, declaring that he was a Roman Hercules.

Commodus was the son of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius and, although the film's scene in which Commodus kills his own father is invention, it is true that Commodus was the very opposite of all that his father had stood for. Vain and pleasure-seeking, Commodus virtually bankrupted the Roman treasury and he sought to fill it up again by having wealthy citizens executed for treason so he could confiscate their property.

Soon, people began plotting against him for real, including his own sister. The plots were foiled, however, and Commodus set about executing still more people, either because they were conspiring against him or because he thought they might do so in the future.

Eventually the Praetorian prefect and the emperor's own court chamberlain hired a professional athlete to strangle Commodus in the bath.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus I (Caracalla) (ruled AD 211–217)

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the son of the highly able and effective emperor Septimius Severus. ‘Caracalla’ was a nickname, derived from a hooded coat from Gaul that he introduced into Rome.

Severus named his younger son, Geta, as co-heir with Caracalla, but the two quickly fell out and civil war seemed imminent until Caracalla averted this scenario by having Geta murdered.

Caracalla dealt brutally with opponents: he set about exterminating Geta's supporters, and similarly wiped out those caught up in one of the city of Alexandria's regular local risings against Roman rule.

Caracalla is remembered for the magnificent bath complex named after him in Rome, and for extending Roman citizenship to all free men within the empire ¬– though he was probably simply trying to raise the money he needed for his own lavish spending. He certainly turned the surplus he inherited from his father into a heavy deficit.

Caracalla was a successful, if ruthless, military commander but he was assassinated by a group of ambitious army officers, including the Praetorian prefect Opellius Macrinus, who promptly proclaimed himself emperor.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus II (Elagabalus) (ruled AD 218–222)

Elagabalus was a relative of Septimius Severus's wife, put forward to challenge Macrinus for the throne after the murder of Caracalla. Elagabalus overthrew Macrinus and promptly embarked on an increasingly eccentric reign. His nickname came from his role as priest of the cult of the Syrian god Elah-Gabal, which he tried to introduce into Rome to universal consternation, even having himself circumcised to show his devotion to the cult.

Elagabalus deliberately offended Roman moral and religious principles, setting up a conical black stone fetish – a symbol of the sun god Sol Invictus Elagabalus – on the Palatine Hill and marrying the chief vestal, for which, under normal circumstances, she should have been put to death.

Romans were particularly offended by Elagabalus’s sexual behaviour – as well as a string of marriages he also openly took male lovers, and he seems to have been what would nowadays be recognised as transgender.

Few historians have much good to say about Elagablus, and eventually the Romans' patience gave out: Elagabalus was murdered in a conspiracy organised by his own grandmother.

Diocletian (AD 284–305)

It may seem unfair to include Diocletian in this group, since he is best known for the risky but sensible decision to divide the government of the Roman empire in two, taking Marcus Aurelius Maximianus as his co-emperor, each with a subordinate known as a Caesar, in a four-way division of power called the tetrarchy.

Diocletian was a good administrator, and managed to hold his divided command structure together at a time when the Roman empire was coming under increasing pressure from its enemies outside its boundaries. What gets Diocletian included here, however, is his utterly ruthless persecution of Christians.

Christians had long been regarded by most Romans with a mixture of distaste and a rather amused tolerance, but Diocletian set about the total eradication of the religion. Churches were to be destroyed, scriptures publicly burnt, and Christian priests imprisoned and forced to conduct sacrifices to the emperor on pain of death. Christians who refused to give up their faith were tortured and executed.

It was an unusually vicious persecution, given that the Romans were usually accepting of other religions, and it reflects Diocletian's fear that, at a time when unity of purpose was essential for the empire's survival, Christianity represented a rejection of Roman religious values that he could not afford to allow.

Sean Lang is a senior lecturer in history at Anglia Ruskin University, and the author of publications including British History for Dummies (2004), European History for Dummies (2011) and First World War for Dummies (2014). You can follow Sean on Twitter @sf_lang.

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors in history | History Extra

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors in history

They are often described as ruthless and bloodthirsty, famous for their tyrannical reigns of terror. Here, historian Sean Lang examines eight of the bloodiest emperors of Ancient Rome…

Monday 18th July 2016

Sean Lang

BBC History Magazine

We all know about the Roman Emperors, don't we? Mad, bad and decidedly dangerous to know. Who can forget Peter Ustinov's Nero in the 1951 epic Quo Vadis?, or John Hurt's tortured and murderous Caligula in the BBC's I, Claudius?

In fact, as historians point out (to anyone who will listen), many of the emperors on the list below were competent – even gifted – administrators, and the sources for some of the more lurid stories about them are not always above suspicion of exaggeration or invention. And some of the crimes that most shocked their contemporaries, like a penchant for performing in public, would not necessarily offend us so much today.

Some emperors, like Nero or Domitian, have passed into history as models of erratic, paranoid tyrants; others, like Diocletian, were able administrators, providing good government (unlessyou happened to be a Christian, in which case you were in great peril). Even under the worst emperors Rome continued to function, but involvement in public life could become a decidedly dangerous business.

Tiberius (ruled AD 14–37)

Tiberius was the successor to Augustus, though Augustus did not particularly want Tiberius to succeed him, and it was only the untimely death of the emperor's grandsons Gaius and Lucius, and Augustus's decision to exile their younger brother, Agrippa Postumus, that put Tiberius in line for the imperial throne.

Tiberius was a gifted military commander and respected the authority of the senate. However, he had a gloomy and increasingly suspicious outlook that won him few friends and led him into a bitter dispute with Agrippina, the widow of his war hero nephew Germanicus. Fatally, Tiberius relied heavily on the ambitious and ruthless Aelius Sejanus, who instituted a reign of terror until Tiberius, learning that Sejanus planned to seize power himself, had him arrested and executed.

Tiberius sank into morbid suspicion of everyone around him: he retreated to the island of Capri and revived the ancient accusation of maiestas (treason) and used it to sentence to death anyone he suspected. Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus give us a picture of Tiberius living on Capri as a depraved sexual predator, which may owe more to colourful imagination than to fact, though he certainly made use of a sheer drop into the sea to dispose of anyone he took issue with. Tiberius was not a monster in the mould of some of his successors, but he certainly set the tone for what was to come.

Gaius (Caligula) (ruled AD 37–41)

Gaius (‘Caligula, or ‘little bootee’ – a childhood nickname given him by his father's troops) is best known for a series of eccentric actions, such as declaring war on the sea and proclaiming himself a god.

His reign actually began quite promisingly, but after a serious bout of illness he developed paranoia that led him into alarmingly erratic behaviour, possibly including incest with his sister, Julia Drusilla, whom he named as his heir.

Gaius took particular delight in humiliating the senate, claiming that he could make anyone consul, even his horse (though, contrary to the popular story, he didn't actually go through with this). As the son of Germanicus [a prominent general], Gaius was keen to establish his military credentials, though his campaign in Germany achieved little and his abortive invasion of Britain had to be turned into a battle with the sea god Neptune: he is said to have told his troops to attack the waves with their swords and gather seashells as booty.

Gaius declared himself a god and used his divine status to establish what was, in effect, an absolutist monarchy in Rome. He followed Tiberius's example of using treason trials to eliminate enemies, real or imagined. In the end it was his rather childish taunting of Cassius Chaerea, a member of the Praetorian guard, which brought Gaius down. Chaerea arranged for his assassination at the Palatine Games. He is supposed to have protested that he couldn't be killed because he was an immortal god, but he turned out to be rather less immortal than he thought.

Nero (ruled AD 54–68 )

Nero is the Roman Emperor we all love to hate, and not without reason. He was actually a competent administrator, and he was aided by some very able men, including his tutor – the writer Seneca. However, he was also unquestionably a murderer, starting with his step-brother Britannicus, with whom he had been supposed to share power, and progressing through his wife Octavia, whom he deserted for his lover, Poppeaea, and then had executed on a trumped-up charge of adultery.

Probably on Poppaea's prompting he had his own mother murdered, though the initial attempt, using a collapsible boat, went wrong, and she had to be beaten to death instead. He then kicked Poppaea to death in a fit of anger while she was pregnant with his child.

Contrary to the myth, Nero did not start the great fire of Rome, nor did he ‘fiddle’ (nor even play the lyre), while the city burned – in fact, he organised relief work for its victims and planned the rebuilding. But Nero’s fondness for his own music and poetry, which made him force senators to sit through his own interminable and talentless recitals, meant people could easily believe it of him.

Nero was much hated for building his huge, tasteless ‘golden house’ complex [aka the Domus Aurea, a large landscaped portico villa] in the ruins of what had been the public area of central Rome. He undoubtedly persecuted Christians in large numbers, and his childish insistence on winning the laurels at the Olympic Games in Greece – whether or not he actually won, or indeed finished the race – brought the whole empire into disrepute.

Nero was toppled by an army revolt that sunk into a destructive three-way civil war.

Domitian (ruled AD 81–96)

Domitian was the younger son of Vespasian, the general who had emerged from the chaos after Nero's fall and restored a certain element of stability and normality to Roman public life.

Domitian inherited none of his father's charm and, like others on this list, he suffered from deep suspicion of those around him, amounting to paranoia, possibly a result of his narrow escape from being killed during the civil war. He was particularly suspicious of the senate and had a number of leading citizens executed for conspiracy against him, including 12 ex-consuls and two of his own cousins.

Domitian’s rule became steadily more autocratic, and he demanded to be treated like a god. He turned against philosophers, sending many of them into exile, and he arranged the judicial murder of the chief vestal virgin, having her buried alive in a specially constructed tomb.

Domitian was eventually brought down by a conspiracy arranged by his wife, Domitia, and was somewhat inexpertly stabbed by a palace servant. Some historians think Domitian's tyranny has been overstated; others have compared him to Saddam Hussein at his most vengeful.

Commodus (ruled AD 180–192)

Commodus was the emperor immortalised by Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000). Commodus was indeed a passionate follower of gladiatorial combat, and himself fought in the arena, sometimes dressed as Hercules, for which he awarded himself divine honours, declaring that he was a Roman Hercules.

Commodus was the son of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius and, although the film's scene in which Commodus kills his own father is invention, it is true that Commodus was the very opposite of all that his father had stood for. Vain and pleasure-seeking, Commodus virtually bankrupted the Roman treasury and he sought to fill it up again by having wealthy citizens executed for treason so he could confiscate their property.

Soon, people began plotting against him for real, including his own sister. The plots were foiled, however, and Commodus set about executing still more people, either because they were conspiring against him or because he thought they might do so in the future.

Eventually the Praetorian prefect and the emperor's own court chamberlain hired a professional athlete to strangle Commodus in the bath.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus I (Caracalla) (ruled AD 211–217)

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the son of the highly able and effective emperor Septimius Severus. ‘Caracalla’ was a nickname, derived from a hooded coat from Gaul that he introduced into Rome.

Severus named his younger son, Geta, as co-heir with Caracalla, but the two quickly fell out and civil war seemed imminent until Caracalla averted this scenario by having Geta murdered.

Caracalla dealt brutally with opponents: he set about exterminating Geta's supporters, and similarly wiped out those caught up in one of the city of Alexandria's regular local risings against Roman rule.

Caracalla is remembered for the magnificent bath complex named after him in Rome, and for extending Roman citizenship to all free men within the empire ¬– though he was probably simply trying to raise the money he needed for his own lavish spending. He certainly turned the surplus he inherited from his father into a heavy deficit.

Caracalla was a successful, if ruthless, military commander but he was assassinated by a group of ambitious army officers, including the Praetorian prefect Opellius Macrinus, who promptly proclaimed himself emperor.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus II (Elagabalus) (ruled AD 218–222)

Elagabalus was a relative of Septimius Severus's wife, put forward to challenge Macrinus for the throne after the murder of Caracalla. Elagabalus overthrew Macrinus and promptly embarked on an increasingly eccentric reign. His nickname came from his role as priest of the cult of the Syrian god Elah-Gabal, which he tried to introduce into Rome to universal consternation, even having himself circumcised to show his devotion to the cult.

Elagabalus deliberately offended Roman moral and religious principles, setting up a conical black stone fetish – a symbol of the sun god Sol Invictus Elagabalus – on the Palatine Hill and marrying the chief vestal, for which, under normal circumstances, she should have been put to death.

Romans were particularly offended by Elagabalus’s sexual behaviour – as well as a string of marriages he also openly took male lovers, and he seems to have been what would nowadays be recognised as transgender.

Few historians have much good to say about Elagablus, and eventually the Romans' patience gave out: Elagabalus was murdered in a conspiracy organised by his own grandmother.

Diocletian (AD 284–305)

It may seem unfair to include Diocletian in this group, since he is best known for the risky but sensible decision to divide the government of the Roman empire in two, taking Marcus Aurelius Maximianus as his co-emperor, each with a subordinate known as a Caesar, in a four-way division of power called the tetrarchy.

Diocletian was a good administrator, and managed to hold his divided command structure together at a time when the Roman empire was coming under increasing pressure from its enemies outside its boundaries. What gets Diocletian included here, however, is his utterly ruthless persecution of Christians.

Christians had long been regarded by most Romans with a mixture of distaste and a rather amused tolerance, but Diocletian set about the total eradication of the religion. Churches were to be destroyed, scriptures publicly burnt, and Christian priests imprisoned and forced to conduct sacrifices to the emperor on pain of death. Christians who refused to give up their faith were tortured and executed.

It was an unusually vicious persecution, given that the Romans were usually accepting of other religions, and it reflects Diocletian's fear that, at a time when unity of purpose was essential for the empire's survival, Christianity represented a rejection of Roman religious values that he could not afford to allow.

Sean Lang is a senior lecturer in history at Anglia Ruskin University, and the author of publications including British History for Dummies (2004), European History for Dummies (2011) and First World War for Dummies (2014). You can follow Sean on Twitter @sf_lang.

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors in history | History Extra