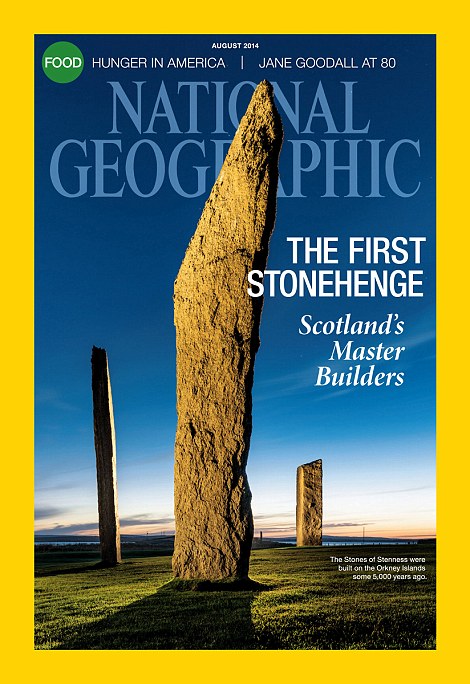

These stunning photographs reveal the standing stones of Stenness in all their glory.

The stones were erected 5,000 years ago way up on Orkney and they form what is probably the oldest henge monument in the UK, around 2,500 years older than even Stonehenge seven hundred miles to the south.

The workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then transported it several miles to a grassy promontory with commanding views of the surrounding countryside.

Their workmanship was impeccable, writes National Geographic's Roff Smith. The imposing walls they built would have done credit to the Roman centurions who, some 30 centuries later, would erect Hadrian's Wall in another part of Britain.

Cloistered within those walls were dozens of buildings, among them one of the largest roofed structures built in prehistoric northern Europe.

The stunning images featured in August's edition of National Geographic.

The first Stonehenge: Breathtaking photos capture the stark beauty of the standing stones of Orkney - built thousands of years before England's most famous neolithic monument

These stunning images show standing stones of Orkney off northern tip of Scotland, built around 5,000 years ago

Workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then took it to grassy area

Walls they built would have done credit to Roman centurions who later erected Hadrian's Wall in another part of UK

By Sam Webb

9 August 2014

Daily Mail

They had Stone Age technology, but their vision was millennia ahead of their time.

Five thousand years ago the ancient inhabitants of Orkney - a fertile, green archipelago off the northern tip of Scotland - erected a complex of monumental buildings unlike anything they had ever attempted before.

These beautiful images, featured in the August issue of National Geographic, capture the structures - built an estimated two and a half thousand years before Stonehenge - in all their grandeur.

Archaeological wonder: The Stones of Stenness may be Britain’s most ancient stone circle

Sentinels by the sea: Orkney’s largest tomb, Maes Howe, is aligned to capture the rays of the setting sun on the eve of the winter solstice. 'Orkney is a key to understanding Neolithic religion,' says site director Nick Card

Blessed: With fertile soil and a mild climate, Orkney was a land of plenty for Neolithic homesteaders. Agricultural wealth helped give them the freedom to pursue grand architectural dreams

The location of Stenness

The workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then transported it several miles to a grassy promontory with commanding views of the surrounding countryside.

Their workmanship was impeccable, writes National Geographic's Roff Smith. The imposing walls they built would have done credit to the Roman centurions who, some 30 centuries later, would erect Hadrian's Wall in another part of Britain.

Cloistered within those walls were dozens of buildings, among them one of the largest roofed structures built in prehistoric northern Europe.

It was more than 80 feet long and 60 feet wide, with walls 13 feet thick. The complex featured paved walkways, carved stonework, coloured facades, even slate roofs - a rare extravagance in an age when buildings were typically roofed with sod, hides, or thatch.

Macabre: In 1958 a farmer digging flagstones accidentally uncovered the 5,000-year-old Tomb of the Eagles. It held more than 16,000 human bones mingled with the talons of white-tailed eagles.

Sheep graze among the Stones of Stenness, which may have been a model for Stonehenge. In 1814 a farmer tried to remove the ancient stones so he could more easily tend his fields

Fast-forward five millennia to a balmy summer afternoon on a scenic headland known as the Ness of Brodgar. Here an eclectic team of archaeologists, university professors, students, and volunteers is bringing to light a collection of grand buildings that long lay hidden beneath a farm field.

Archaeologist Nick Card, excavation director with the Archaeology Institute at the University of the Highlands and Islands, said the recent discovery of these stunning ruins is turning British prehistory on its head.

'This is almost on the scale of some of the great classical sites in the Mediterranean, like the Acropolis in Greece, except these structures are 2,500 years older,' he said.

'Like the Acropolis, this was built to dominate the landscape - to impress, awe, inspire, perhaps even intimidate anyone who saw it. The people who built this thing had big ideas. They were out to make a statement.'

The full article and pictures appear in the August issue of National Geographic. Bottom, this domino-sized figure is the earliest depiction of a human face found in Britain

What that statement was, and for whom it was intended, remains a mystery, as does the purpose of the complex itself. Although it's usually referred to as a temple, it's likely to have fulfilled a variety of functions during the thousand years it was in use.

'It's clear that many people gathered here for seasonal rituals, feasts, and trade. I've heard this place called the Egypt of the North,' saidarchaeologist Julie Gibson, who came to Orkney more than 30 years ago to excavate a Viking cemetery and never left.

'Turn over a rock around here and you're likely to find a new site.'

The stones were erected 5,000 years ago way up on Orkney and they form what is probably the oldest henge monument in the UK, around 2,500 years older than even Stonehenge seven hundred miles to the south.

The workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then transported it several miles to a grassy promontory with commanding views of the surrounding countryside.

Their workmanship was impeccable, writes National Geographic's Roff Smith. The imposing walls they built would have done credit to the Roman centurions who, some 30 centuries later, would erect Hadrian's Wall in another part of Britain.

Cloistered within those walls were dozens of buildings, among them one of the largest roofed structures built in prehistoric northern Europe.

The stunning images featured in August's edition of National Geographic.

The first Stonehenge: Breathtaking photos capture the stark beauty of the standing stones of Orkney - built thousands of years before England's most famous neolithic monument

These stunning images show standing stones of Orkney off northern tip of Scotland, built around 5,000 years ago

Workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then took it to grassy area

Walls they built would have done credit to Roman centurions who later erected Hadrian's Wall in another part of UK

By Sam Webb

9 August 2014

Daily Mail

They had Stone Age technology, but their vision was millennia ahead of their time.

Five thousand years ago the ancient inhabitants of Orkney - a fertile, green archipelago off the northern tip of Scotland - erected a complex of monumental buildings unlike anything they had ever attempted before.

These beautiful images, featured in the August issue of National Geographic, capture the structures - built an estimated two and a half thousand years before Stonehenge - in all their grandeur.

Archaeological wonder: The Stones of Stenness may be Britain’s most ancient stone circle

Sentinels by the sea: Orkney’s largest tomb, Maes Howe, is aligned to capture the rays of the setting sun on the eve of the winter solstice. 'Orkney is a key to understanding Neolithic religion,' says site director Nick Card

Blessed: With fertile soil and a mild climate, Orkney was a land of plenty for Neolithic homesteaders. Agricultural wealth helped give them the freedom to pursue grand architectural dreams

The location of Stenness

The workers quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then transported it several miles to a grassy promontory with commanding views of the surrounding countryside.

Their workmanship was impeccable, writes National Geographic's Roff Smith. The imposing walls they built would have done credit to the Roman centurions who, some 30 centuries later, would erect Hadrian's Wall in another part of Britain.

Cloistered within those walls were dozens of buildings, among them one of the largest roofed structures built in prehistoric northern Europe.

It was more than 80 feet long and 60 feet wide, with walls 13 feet thick. The complex featured paved walkways, carved stonework, coloured facades, even slate roofs - a rare extravagance in an age when buildings were typically roofed with sod, hides, or thatch.

Macabre: In 1958 a farmer digging flagstones accidentally uncovered the 5,000-year-old Tomb of the Eagles. It held more than 16,000 human bones mingled with the talons of white-tailed eagles.

Sheep graze among the Stones of Stenness, which may have been a model for Stonehenge. In 1814 a farmer tried to remove the ancient stones so he could more easily tend his fields

Fast-forward five millennia to a balmy summer afternoon on a scenic headland known as the Ness of Brodgar. Here an eclectic team of archaeologists, university professors, students, and volunteers is bringing to light a collection of grand buildings that long lay hidden beneath a farm field.

Archaeologist Nick Card, excavation director with the Archaeology Institute at the University of the Highlands and Islands, said the recent discovery of these stunning ruins is turning British prehistory on its head.

'This is almost on the scale of some of the great classical sites in the Mediterranean, like the Acropolis in Greece, except these structures are 2,500 years older,' he said.

'Like the Acropolis, this was built to dominate the landscape - to impress, awe, inspire, perhaps even intimidate anyone who saw it. The people who built this thing had big ideas. They were out to make a statement.'

The full article and pictures appear in the August issue of National Geographic. Bottom, this domino-sized figure is the earliest depiction of a human face found in Britain

What that statement was, and for whom it was intended, remains a mystery, as does the purpose of the complex itself. Although it's usually referred to as a temple, it's likely to have fulfilled a variety of functions during the thousand years it was in use.

'It's clear that many people gathered here for seasonal rituals, feasts, and trade. I've heard this place called the Egypt of the North,' saidarchaeologist Julie Gibson, who came to Orkney more than 30 years ago to excavate a Viking cemetery and never left.

'Turn over a rock around here and you're likely to find a new site.'

Last edited: