The Bayeux Tapestry, designed and constructed in England by Anglo-Saxon artists and stitched by Anglo-Saxon seamsters, who were famous across Europe, is arguably the most famous piece of embroidery (it's not actually a tapestry) in history.

Yet, when it was rediscovered 300 years ago, the final section appeared to be missing.

Until now, thanks to the residents of the Channel Island of Alderney....

Bayeux Tapestry: The islanders who finished the final scenes

By Ben Chapple

BBC News

1 July 2014

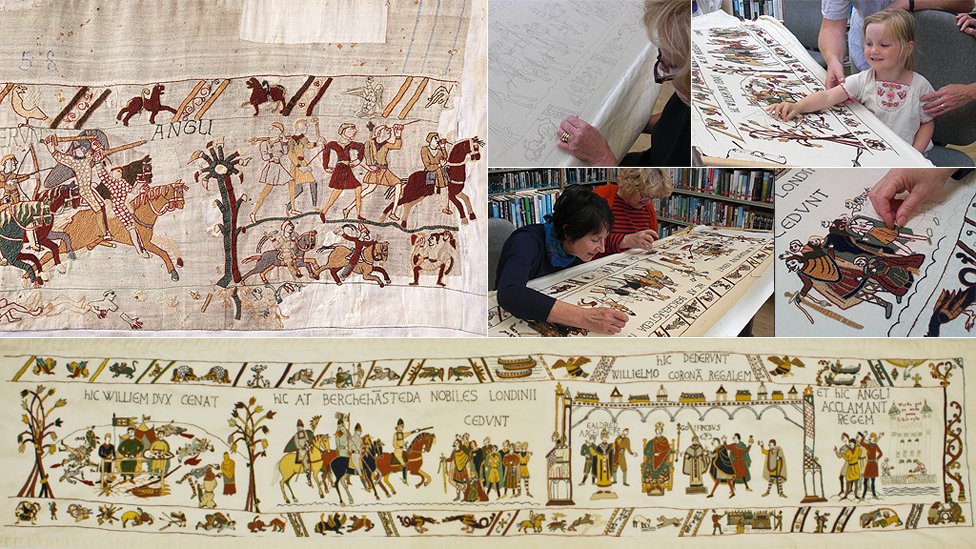

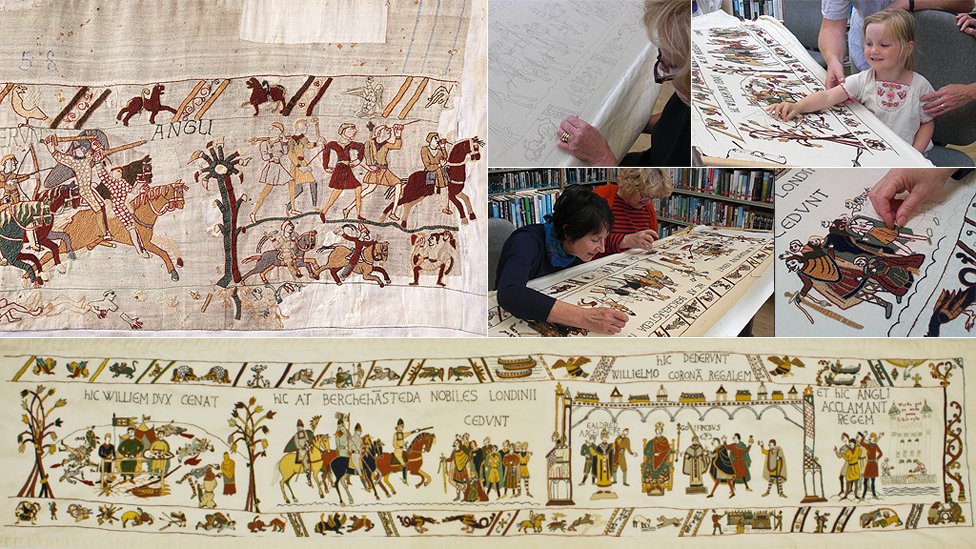

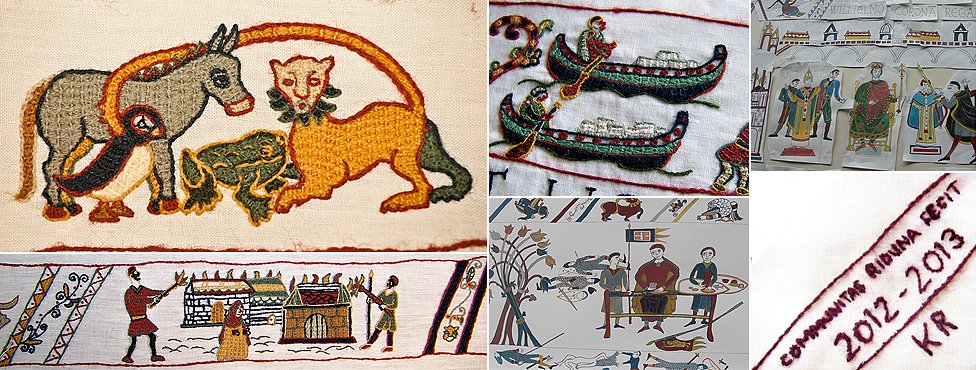

The original tapestry (top left) ends with the Anglo-Saxons fleeing the battlefield but the new ending features William's coronation in Westminster Abbey

Nearly 1,000 years ago, as William the Conqueror sat on his newly-won English throne, a team of embroiderers laboured over a tapestry intended to immortalise his achievement.

The tapestry, chronicling the Norman conquest of England and that battle in 1066, is regarded as a marvel of medieval Europe. However, since it was "rediscovered" by scholars in the 18th Century, its original final scene has been missing.

Instead, the final scenes showed the death of Harold (II) Godwinson, the Anglo-Saxon king, and his unarmoured troops fleeing following their defeat at Hastings. No one is certain how much longer the original tapestry was or what it showed, but most experts believe it was an 8-10ft (2.5-3m) piece including a depiction of William's coronation on Christmas Day in 1066.

Now, a team of embroiderers on Alderney, a small island just off the coast of William's native Normandy, have "finished" the job. The project took a year to complete and every effort was made to ensure it fitted in with its famous forebear. Embroiders used the same techniques, fabrics, colours and similar types of wool to the medieval original.

The new tapestry is the same height as the original and 10ft (3m) long, with four panels showing events following the Battle of Hastings, culminating in William's coronation. The finished work is set to be displayed in the room next to the original tapestry at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum in Normandy.

Alderney - part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency - is an island, one of Britain's Channel Islands, off the coast of Normandy

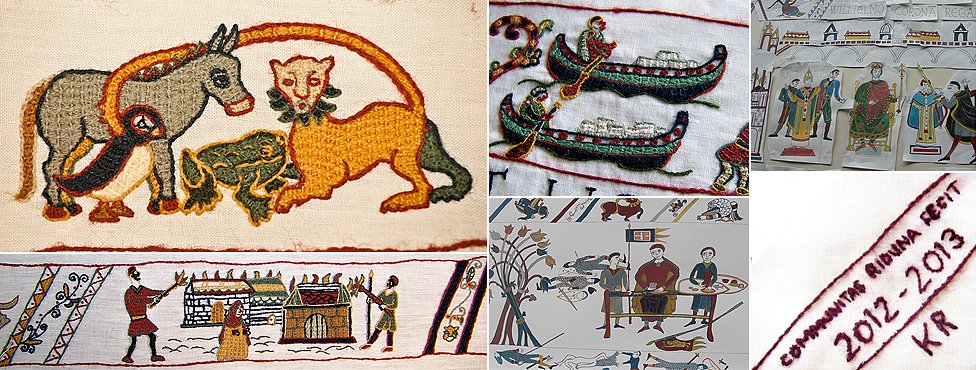

The first of four scenes shows William and his half-brothers dining on the battlefield at Hastings and the second shows high ranking nobles surrendering

William's worried look as he is crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066 may be due to the shout of acclamation from inside the abbey, which was mistaken by the Normans outside as a cry of Anglo-Saxon rebellion and led to them burning Southwark. Chroniclers record that William was trembling during the events happening outside.

"Once you've stitched for a couple of hours you stand back to see what you've done... everyone is so proud of it, of taking part," said Fran Harvey, one of the Alderney stitchers.

"It becomes like a drug. I'd tell my husband I'm just going to pop to the library for half an hour and return two and a half hours later."

As well as the pride in their efforts, she said her shoulders, neck and back had ached after a couple of hours of stitching.

"Hundreds of years have passed, but it's the same physical experience. While we were stitching we chatted, swapped recipes... probably exactly the same things the original embroiders talked about."

Professor Robert Bartlett, a leading authority on the Middle Ages who has presented several BBC TV series, says he has been impressed by the finished effort.

"I think they have made a remarkably good job of getting this imagined section to look very like the rest of the tapestry: its scale and design, with an illustrated border above and below the main panel, the lettering, the postures of the figures," he says.

"It has often been pointed out that the opening of the tapestry has a figure of King Edward the Confessor enthroned, and that around the middle point of the tapestry there is an image of William's enemy Harold enthroned.

"It would be a neat symmetry and make perfect sense of the story if the end of the tapestry had showed the victorious William enthroned, which is what the Alderney team have chosen to do. The other 'new' scenes are more speculative, but they are modelled on scenes earlier in the tapestry so look convincing."

The finished work has been on display in the Alderney Museum until last week, when it was transported to Bayeux. It has been favourably received by Bayeux Tapestry Museum's curator, Sylvette Lemagnen.

"It's remarkably embroidered and the scene is absolutely plausible," she says. "The chosen colours are quite similar to the original.

The characters in the central part of the tapestry are embroidered in a similar style and the animals which decorate the borders conform to the original."

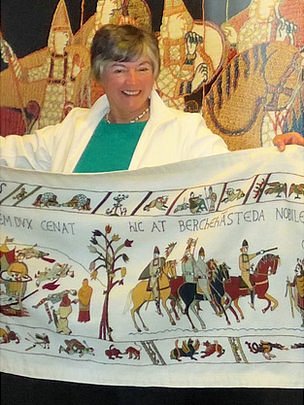

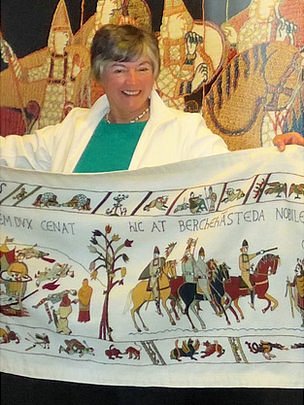

The exhibition in Bayeux marks the culmination of a dream for Kate Russell, who spearheaded the project. She said she had been "a bit obsessed" about the Bayeux Tapestry since first viewing it many years ago.

Among the details in the borders are the animals which still represent the Channel Islands - a donkey for Guernsey, toad for Jersey, puffin for Alderney - and the English lion

The 72-year-old American, who retired to Alderney, currently works at the island's library where the embroidery was done.

She said she was amazed by the response to her idea, which has been financially supported by the States of Alderney. "I had no idea if this would work, never in a million years imagined how popular it would be. Now to have Bayeux Museum want to display it - wow."

Mrs Russell described taking the tapestry to the museum as the "best day of my life, I couldn't stop grinning". She said the project's design was inspired by Jan Messent, author of The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers' Story, who allowed some of her images to be used by the Alderney volunteers.

Kate Russell said she continued to be amazed at the passion people had shown for the project

The project drew on the expertise of islanders, visitors and their contacts, including Jane Bliss, a freelance researcher for Oxford University, who frequently holidays on the island and contacted other academics about historical questions.

These included whether any of the protagonists should look out from the tapestry directly towards the viewer.

In the original tapestry, only Harold Godwinson and the Archbishop of Canterbury did this, during Harold's coronation. It was decided that William and the archbishop should also be shown full faced in the coronation scene.

The embroiderers had also asked whether William's knights would have worn armour inside Westminster Abbey for the coronation, but could find no definitive answer. Mrs Russell said this was an example of when they had "had to find our own way".

The tapestry has only deviated from the original style in one significant way. The final panel includes the image of the Tower of London, even though no other castles feature in the original tapestry.

Mrs Russell said this was a nod to the importance of castles to the Normans.

"Fortifications had only been defensive structures in the past, but these offensive and defensive fortifications allowed the Normans to rule a huge nation with a fairly small number of troops," she says.

Above the tower appears a 'Hand of God' identical to the one shown above Westminster Abbey in the scene showing Harold's coronation.

Although all other writing in the tapestry is in Latin, this features an Old English (Anglo-Saxon) phrase from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1066 - "Wurðe god se end þonne God wylle." It translates as: "The end will be good, as God wills." It can be interpreted differently from either an English or Norman point of view.

"Anglo-Saxons used tapestries to tell stories, but the Normans did not do it previously," Mrs Russell says. "There's a lot of English slant to the tale, it makes Harold seem like a hero - the English embroiders were protecting their own history."

Prof Bartlett, who is based at the University of St Andrews, said the original tapestry was a hugely significant historical artefact. "There is nothing like it from this period: an almost perfectly preserved narrative embroidery, 70m long and over 900 years old.

"It tells the story of an event that changed the history of England and Normandy fundamentally. England and France have never been more intermeshed than they were in the Middle Ages and the tapestry shows how this happened - in pictures."

The Alderney Tapestry will be on display at Bayeux from 1 July till 31 August 2014.

Bayeux Tapestry

William the Conqueror's half-brother Bishop Odo is believed to have commissioned the tapestry to celebrate victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. It is believed to have been stitched by Anglo-Saxon seamsters in England, who were renowned throughout Europe

It shows events from a Norman point of view, from the death of King Edward the Confessor until the Norman victory over the English

The missing section is believed to have shown William's coronation

It is thought to have been unveiled in 1077 at the dedication of Bayeux Cathedral

The first written mention of it is in an inventory of the treasures of Bayeux Cathedral carried out in 1476

According to legend, French revolutionary soldiers took it from the cathedral intending to cut it up to use as wagon covers, but it was saved by a lawyer

In 1804 the tapestry was displayed in Paris as part of propaganda surrounding Emperor Napoleon's planned invasion of Britain

During the 19th Century the tapestry was restored

In 1944, the tapestry was exhibited in Paris for the second time and was then returned to Bayeux

Since 1983, it has been preserved in the former seminary that houses the museum

The Battle of Hastings

Edward the Confessor's death in 1066 left a disputed succession and the throne was seized by his leading aristocrat Harold Godwinson

King Harold quickly faced invasion on two fronts - from the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada, who also claimed the English throne, and William, Duke of Normandy

The Norwegian invasion was stopped at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire on 25 September 1066

Harold then marched his victorious army south but the last Anglo-Saxon king was killed by William's army at the Battle of Hastings fought on 14 October 1066

Re-enact the battle which changed the face of England

BBC News - Bayeux Tapestry: The islanders who finished the final scenes

Yet, when it was rediscovered 300 years ago, the final section appeared to be missing.

Until now, thanks to the residents of the Channel Island of Alderney....

Bayeux Tapestry: The islanders who finished the final scenes

By Ben Chapple

BBC News

1 July 2014

The original tapestry (top left) ends with the Anglo-Saxons fleeing the battlefield but the new ending features William's coronation in Westminster Abbey

Nearly 1,000 years ago, as William the Conqueror sat on his newly-won English throne, a team of embroiderers laboured over a tapestry intended to immortalise his achievement.

The tapestry, chronicling the Norman conquest of England and that battle in 1066, is regarded as a marvel of medieval Europe. However, since it was "rediscovered" by scholars in the 18th Century, its original final scene has been missing.

Instead, the final scenes showed the death of Harold (II) Godwinson, the Anglo-Saxon king, and his unarmoured troops fleeing following their defeat at Hastings. No one is certain how much longer the original tapestry was or what it showed, but most experts believe it was an 8-10ft (2.5-3m) piece including a depiction of William's coronation on Christmas Day in 1066.

Now, a team of embroiderers on Alderney, a small island just off the coast of William's native Normandy, have "finished" the job. The project took a year to complete and every effort was made to ensure it fitted in with its famous forebear. Embroiders used the same techniques, fabrics, colours and similar types of wool to the medieval original.

The new tapestry is the same height as the original and 10ft (3m) long, with four panels showing events following the Battle of Hastings, culminating in William's coronation. The finished work is set to be displayed in the room next to the original tapestry at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum in Normandy.

Alderney - part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency - is an island, one of Britain's Channel Islands, off the coast of Normandy

The first of four scenes shows William and his half-brothers dining on the battlefield at Hastings and the second shows high ranking nobles surrendering

William's worried look as he is crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066 may be due to the shout of acclamation from inside the abbey, which was mistaken by the Normans outside as a cry of Anglo-Saxon rebellion and led to them burning Southwark. Chroniclers record that William was trembling during the events happening outside.

"Once you've stitched for a couple of hours you stand back to see what you've done... everyone is so proud of it, of taking part," said Fran Harvey, one of the Alderney stitchers.

"It becomes like a drug. I'd tell my husband I'm just going to pop to the library for half an hour and return two and a half hours later."

As well as the pride in their efforts, she said her shoulders, neck and back had ached after a couple of hours of stitching.

"Hundreds of years have passed, but it's the same physical experience. While we were stitching we chatted, swapped recipes... probably exactly the same things the original embroiders talked about."

Professor Robert Bartlett, a leading authority on the Middle Ages who has presented several BBC TV series, says he has been impressed by the finished effort.

"I think they have made a remarkably good job of getting this imagined section to look very like the rest of the tapestry: its scale and design, with an illustrated border above and below the main panel, the lettering, the postures of the figures," he says.

"It has often been pointed out that the opening of the tapestry has a figure of King Edward the Confessor enthroned, and that around the middle point of the tapestry there is an image of William's enemy Harold enthroned.

"It would be a neat symmetry and make perfect sense of the story if the end of the tapestry had showed the victorious William enthroned, which is what the Alderney team have chosen to do. The other 'new' scenes are more speculative, but they are modelled on scenes earlier in the tapestry so look convincing."

The finished work has been on display in the Alderney Museum until last week, when it was transported to Bayeux. It has been favourably received by Bayeux Tapestry Museum's curator, Sylvette Lemagnen.

"It's remarkably embroidered and the scene is absolutely plausible," she says. "The chosen colours are quite similar to the original.

The characters in the central part of the tapestry are embroidered in a similar style and the animals which decorate the borders conform to the original."

The exhibition in Bayeux marks the culmination of a dream for Kate Russell, who spearheaded the project. She said she had been "a bit obsessed" about the Bayeux Tapestry since first viewing it many years ago.

Among the details in the borders are the animals which still represent the Channel Islands - a donkey for Guernsey, toad for Jersey, puffin for Alderney - and the English lion

The 72-year-old American, who retired to Alderney, currently works at the island's library where the embroidery was done.

She said she was amazed by the response to her idea, which has been financially supported by the States of Alderney. "I had no idea if this would work, never in a million years imagined how popular it would be. Now to have Bayeux Museum want to display it - wow."

Mrs Russell described taking the tapestry to the museum as the "best day of my life, I couldn't stop grinning". She said the project's design was inspired by Jan Messent, author of The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers' Story, who allowed some of her images to be used by the Alderney volunteers.

Kate Russell said she continued to be amazed at the passion people had shown for the project

The project drew on the expertise of islanders, visitors and their contacts, including Jane Bliss, a freelance researcher for Oxford University, who frequently holidays on the island and contacted other academics about historical questions.

These included whether any of the protagonists should look out from the tapestry directly towards the viewer.

In the original tapestry, only Harold Godwinson and the Archbishop of Canterbury did this, during Harold's coronation. It was decided that William and the archbishop should also be shown full faced in the coronation scene.

The embroiderers had also asked whether William's knights would have worn armour inside Westminster Abbey for the coronation, but could find no definitive answer. Mrs Russell said this was an example of when they had "had to find our own way".

The tapestry has only deviated from the original style in one significant way. The final panel includes the image of the Tower of London, even though no other castles feature in the original tapestry.

Mrs Russell said this was a nod to the importance of castles to the Normans.

"Fortifications had only been defensive structures in the past, but these offensive and defensive fortifications allowed the Normans to rule a huge nation with a fairly small number of troops," she says.

Above the tower appears a 'Hand of God' identical to the one shown above Westminster Abbey in the scene showing Harold's coronation.

Although all other writing in the tapestry is in Latin, this features an Old English (Anglo-Saxon) phrase from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1066 - "Wurðe god se end þonne God wylle." It translates as: "The end will be good, as God wills." It can be interpreted differently from either an English or Norman point of view.

"Anglo-Saxons used tapestries to tell stories, but the Normans did not do it previously," Mrs Russell says. "There's a lot of English slant to the tale, it makes Harold seem like a hero - the English embroiders were protecting their own history."

Prof Bartlett, who is based at the University of St Andrews, said the original tapestry was a hugely significant historical artefact. "There is nothing like it from this period: an almost perfectly preserved narrative embroidery, 70m long and over 900 years old.

"It tells the story of an event that changed the history of England and Normandy fundamentally. England and France have never been more intermeshed than they were in the Middle Ages and the tapestry shows how this happened - in pictures."

The Alderney Tapestry will be on display at Bayeux from 1 July till 31 August 2014.

Bayeux Tapestry

William the Conqueror's half-brother Bishop Odo is believed to have commissioned the tapestry to celebrate victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. It is believed to have been stitched by Anglo-Saxon seamsters in England, who were renowned throughout Europe

It shows events from a Norman point of view, from the death of King Edward the Confessor until the Norman victory over the English

The missing section is believed to have shown William's coronation

It is thought to have been unveiled in 1077 at the dedication of Bayeux Cathedral

The first written mention of it is in an inventory of the treasures of Bayeux Cathedral carried out in 1476

According to legend, French revolutionary soldiers took it from the cathedral intending to cut it up to use as wagon covers, but it was saved by a lawyer

In 1804 the tapestry was displayed in Paris as part of propaganda surrounding Emperor Napoleon's planned invasion of Britain

During the 19th Century the tapestry was restored

In 1944, the tapestry was exhibited in Paris for the second time and was then returned to Bayeux

Since 1983, it has been preserved in the former seminary that houses the museum

The Battle of Hastings

Edward the Confessor's death in 1066 left a disputed succession and the throne was seized by his leading aristocrat Harold Godwinson

King Harold quickly faced invasion on two fronts - from the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada, who also claimed the English throne, and William, Duke of Normandy

The Norwegian invasion was stopped at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire on 25 September 1066

Harold then marched his victorious army south but the last Anglo-Saxon king was killed by William's army at the Battle of Hastings fought on 14 October 1066

Re-enact the battle which changed the face of England

BBC News - Bayeux Tapestry: The islanders who finished the final scenes

Last edited: