From the train to the jet engine; from the television to photography; and from the marine chronometer to the computer and the World Wide Web, British inventions have helped bring in the modern age.

Here we celebrate the inventors and inventions that put the ‘great’ into Great Britain.

Fathers of invention

British inventors © Superstock / Alamy / The Science Museum

British inventors © Superstock / Alamy / The Science Museum

“This is for everyone”. Four simple words, in huge, animated letters, swirled around the Olympic Stadium as part of the opening ceremony for London 2012. The message was activated, by computer, by a relatively little-known man in the middle of the stadium. He was Sir Tim Berners-Lee, whose World Wide Web has been compared in importance to Gutenberg’s printing press by Time magazine. He is among the latest in a long line of remarkable British inventors who have helped to change the world.

Born in London in 1955, Tim was fascinated from an early age with the way the human mind organises and connects seemingly unrelated information. At Queens College, Oxford he built his first computer using a soldering iron and secondhand television, before gaining a physics degree. His Internet based system of information sharing, based on ‘hypertext’, was revealed in 1989 and the first ‘web site’ followed two years later. Thanks to his work, the Internet went from something technical, used only by scientists and the military, to a tool accessible to all, almost overnight. Ever since, he has worked to keep the Web open and free ‘for everyone’.

The opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games © Marko Djurica / Reuters

The first ever website, August 1991. The website was simply an explanation of what the World Wide Web was and served as a directory to find other websites - despite the fact that no other websites existed

Two hundred and fifty years ago another British invention also revolutionised communication, this time by sea. John Harrison’s marine chronometer helped the country achieve pre-eminence as a trading nation. Knowing the time at two reference points was necessary to calculate longitude but pendulum clocks weren’t suited to sea travel. Until Harrison’s device was developed, ships faced the potentially fatal prospect of getting lost, as captains had only the position of moon and stars, charted at the new-fangled Royal Observatory, with which to estimate their position. The government offered a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could find a more accurate system. Harrison, a Lincolnshire carpenter, set about solving the problem by building a portable clock which would not be affected by a ship’s movement. His winning timepiece, the marine timekeeper H4 of 1759, was tried on a voyage to Jamaica in 1761 and found to be only five seconds slow. When Captain James Cook set sail on his second voyage of discovery, lasting three years, it was with a Harrison designed watch. He reported it was never more than eight seconds out.

John Harrison; one of Harrison’s timepieces are displayed at Greenwich Royal Observatory © The Art

Gallery Collection / Alamy

Several of Harrison’s timepieces are displayed at the home of world time, Greenwich, in Flamsteed House, the Old Royal Observatory. On his tomb in St John Churchyard, Hampstead are the words ‘The man who discovered longitude’.

For our next great man (alas, all our examples are male) we move from a regal observatory to a small, oil-lit outhouse. As your eyes adapt to the dark recesses of James Watt’s workshop you become aware that, like most great inventors, he was a tinkerer at heart.

Pots, tools, screws, bolts, rules, dividers and plaster casts are strewn about and drawers and shelves are full to overflowing. The den now has pride of place in London’s Science Museum. Though Watt didn’t invent the steam engine – that honour goes to Englishman Thomas Newcomen – his improvements created something twice as powerful and three times as efficient. He teamed up with businessman Matthew Boulton in Birmingham and, from 1774, their Soho Manufactory turned out the engines that powered the Industrial Revolution. By using a separate condenser, the machines’ efficiency grew exponentially. Creating a rotary motion allowed them to run looms, mint coins and hammer iron. Several times a year, Watt’s Smethwick Engine, a giant machine the height of four men, hisses, clunks and creaks into life at the city’s Thinktank science museum. Designed in 1778, it’s the world’s oldest working steam engine and ran constantly for 112 years. Powerful testament to a mechanical genius.

James Watt / The Rocket on display at the Science Museum © National Portrait Gallery, London / Science Museums PL

Robert Stephenson’s Rocket was the premier inter-city locomotive, winning the Rainhill Trials, a competition held 25 years later to choose motive power for the new Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Built in Newcastle, it incorporated important new features, notably a multi-tubular boiler. This enabled its fire to heat water more efficiently, becoming the basis for every steam locomotive built since. It travelled at the remarkable speed of almost thirty miles-per-hour. Robert, born in a cottage near Newcastle in 1803, was the son of pioneering railway and engine builder George Stephenson, with whom he worked closely. On his death, aged just 55, he was buried beside kings and princes at Westminster Abbey and, in his eulogy, was described as ‘the greatest engineer of the present century’. His statue has pride of place outside Euston Station, London’s first railway terminus. You can often see a replica of Rocket in action at the National Railway Museum in York, while the Science Museum has the original.

Fox Talbot outside his photographic studio in Reading, Berkshire, in 1845 © World History Archive / Alamy

Five years after Rocket took to the tracks, a pioneer of photography sealed his place in history. William Henry Fox Talbot created the first permanent negative image, using paper soaked in silver chloride. This was the beginning of the negative/positive process, which he later called ‘calotype’, that became standard in most photography until the age of digital imaging. The oldest surviving negative, exposed in August 1835, pictures an oriel window at his home, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, where he conducted his experiments. Fox Talbot also discovered the use of gallic acid to develop the latent image on exposed film. In 1844 he produced The Pencil of Nature, the first commercial book illustrated entirely by photographs. A hundred years later his descendants gave the house and the surrounding village to the National Trust. Now this beautiful location is often used as a location for period dramas while William and his family rest in the village cemetery.

(Right) The 1835 photo of a window at Fox Talbot's home, Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire came from the world's first negative (left)

A photo of a coachman taken by William Fox Talbot in 1840 at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire where Talbot had his photographic studio. It is the earliest known photograph of a human being on paper.

The Open Door, Fox Talbot, 1843

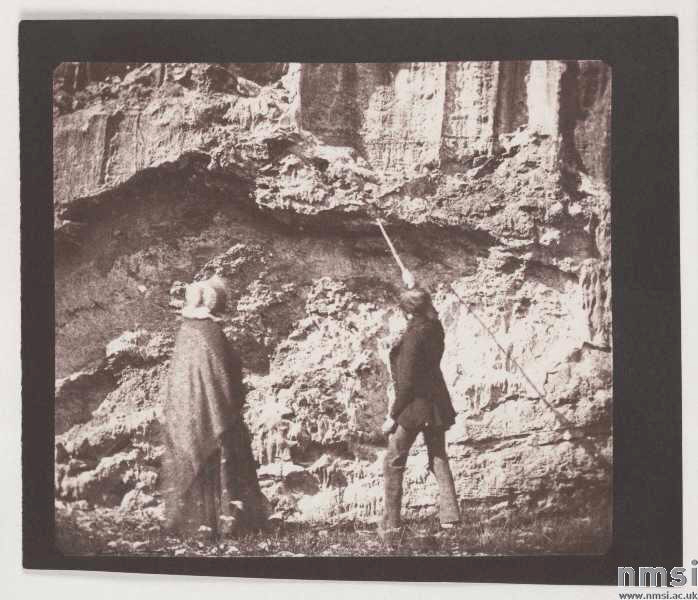

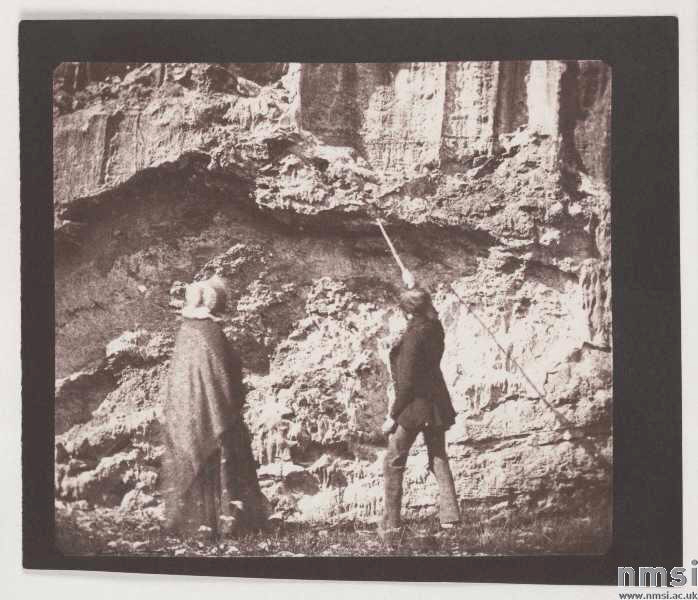

"The Geologists, Chudleigh, Devon" by William Henry Fox Talbot, 1843

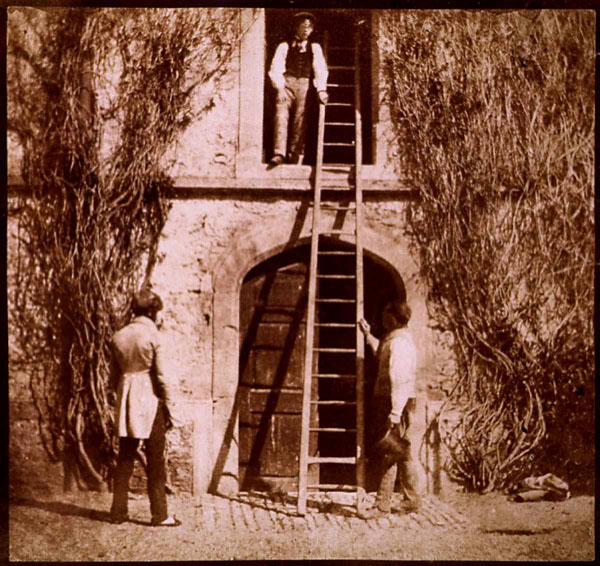

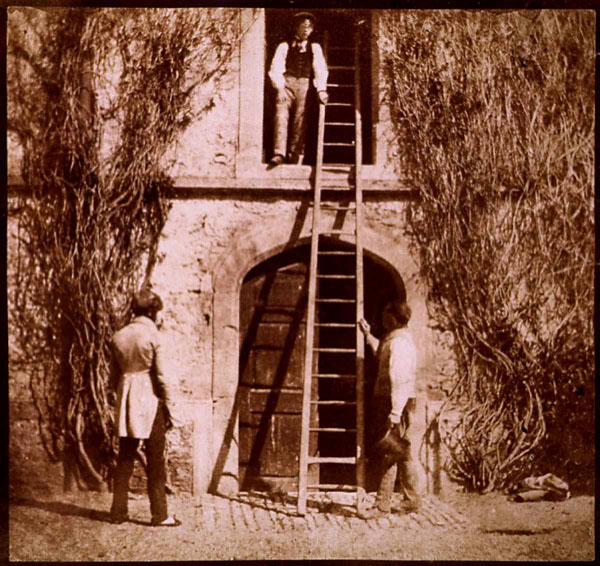

"The Ladder" - William Fox Talbot, April 1844, Wiltshire

Charles Babbage, 1840 © SMSSPL

While Fox Talbot was experimenting with light and chemicals, a contemporary was obsessing over mathematical conundrums.

Charles Babbage, the son of a rich Devon banker, sought a way to eliminate error in complicated calculations. These required the use of printed mathematical tables, which were prone to inaccuracy. Despite working in the mechanical rather than the electronic age, Babbage is regarded as the father of the programmable computer. His inventions were heavy, cumbersome, incredibly complex – and, partly because of this, never completed! His Difference Engine No 1, a calculating machine, would, if completed, have had 25,000 parts, stood eight feet long, seven high and three deep. This was nothing compared to his Analytical Engine. A major intellectual feat of the age, conceived in 1834, it possessed all the features of a basic, modern computer. When the Science Museum built his Difference Engine No 2 from original drawings in 1985, it contained 4,000 moving parts, weighed 2.6 tonnes and worked perfectly. A plaque marks the house in Dorset Street, Marylebone where he lived and worked. His grave of 1871 can be seen in London’s first commercial necropolis, Kensal Green Cemetery.

The world’s one billion television sets owe their existence to a Scot, John Logie Baird, born in 1888 near the River Clyde in Helensburgh. Though the cathode ray tube, which converted electricity into light on a screen, had been invented sometime before, it was Baird who, in London in 1926, first demonstrated his ‘televisor’ – a televised moving image of a person in his attic laboratory at 22 Frith Street, Soho. It hadn’t been easy: earlier experiments in his Hastings laboratory, using a transmitter and receiver created from biscuit tins, penny lenses and string, led to a small explosion, after which his landlord evicted him.

Alexandra Palace © Alex Segre / Alamy

In 1936 an early BBC transmitter, on a hilltop overlooking London at Alexandra Palace, began beaming pictures created on his mechanical, 240-line system. EMI-Marconi’s rival electronic system using 405 lines, trialled simultaneously, ultimately won the day but Baird was the pioneer and went on to invent colour, stereoscopic and big screen television. By the time the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was televised in 1953, the ‘small screen’ was the must-have household gadget. To see some of Baird’s original apparatus in the National Media Museum in Bradford is to return to the exciting early days of grey, flickering ‘pictures by wireless’.

Sir Frank Whittle © Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy

Our final subject, Sir Frank Whittle, was small in stature. It took three attempts and a high-calorie eating regime before the RAF would recruit him – yet he stands tall among British inventors. The Coventry-born creator of the first jet engine was only 22 when he realised that piston-powered flight was yesterday’s technology. While still at flying school in 1929, he designed a gas turbine that could

become a power source for jet thrust, patenting his ‘turbo-jet’ the following year. Unfortunately, the Air Ministry failed to recognise the invention’s potential for speed. It was years before work started on a prototype in Lutterworth, Leicestershire. Eventually, in 1941 at the height of World War II, a test pilot powered his Gloster E28/39 (later the Gloster Meteor) off the runway at RAF Cranwell, Lincolnshire. The age of Allied jet flight had begun. Who knows what life-changing invention a Brit will create next?

The RAF's Gloster Meteor, the Allies' first operational jet aircraft

- See more at: Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture - Fathers of invention

Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture - Fathers of invention

Here we celebrate the inventors and inventions that put the ‘great’ into Great Britain.

Fathers of invention

“This is for everyone”. Four simple words, in huge, animated letters, swirled around the Olympic Stadium as part of the opening ceremony for London 2012. The message was activated, by computer, by a relatively little-known man in the middle of the stadium. He was Sir Tim Berners-Lee, whose World Wide Web has been compared in importance to Gutenberg’s printing press by Time magazine. He is among the latest in a long line of remarkable British inventors who have helped to change the world.

Born in London in 1955, Tim was fascinated from an early age with the way the human mind organises and connects seemingly unrelated information. At Queens College, Oxford he built his first computer using a soldering iron and secondhand television, before gaining a physics degree. His Internet based system of information sharing, based on ‘hypertext’, was revealed in 1989 and the first ‘web site’ followed two years later. Thanks to his work, the Internet went from something technical, used only by scientists and the military, to a tool accessible to all, almost overnight. Ever since, he has worked to keep the Web open and free ‘for everyone’.

The opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games © Marko Djurica / Reuters

The first ever website, August 1991. The website was simply an explanation of what the World Wide Web was and served as a directory to find other websites - despite the fact that no other websites existed

Two hundred and fifty years ago another British invention also revolutionised communication, this time by sea. John Harrison’s marine chronometer helped the country achieve pre-eminence as a trading nation. Knowing the time at two reference points was necessary to calculate longitude but pendulum clocks weren’t suited to sea travel. Until Harrison’s device was developed, ships faced the potentially fatal prospect of getting lost, as captains had only the position of moon and stars, charted at the new-fangled Royal Observatory, with which to estimate their position. The government offered a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could find a more accurate system. Harrison, a Lincolnshire carpenter, set about solving the problem by building a portable clock which would not be affected by a ship’s movement. His winning timepiece, the marine timekeeper H4 of 1759, was tried on a voyage to Jamaica in 1761 and found to be only five seconds slow. When Captain James Cook set sail on his second voyage of discovery, lasting three years, it was with a Harrison designed watch. He reported it was never more than eight seconds out.

John Harrison; one of Harrison’s timepieces are displayed at Greenwich Royal Observatory © The Art

Gallery Collection / Alamy

Several of Harrison’s timepieces are displayed at the home of world time, Greenwich, in Flamsteed House, the Old Royal Observatory. On his tomb in St John Churchyard, Hampstead are the words ‘The man who discovered longitude’.

For our next great man (alas, all our examples are male) we move from a regal observatory to a small, oil-lit outhouse. As your eyes adapt to the dark recesses of James Watt’s workshop you become aware that, like most great inventors, he was a tinkerer at heart.

Pots, tools, screws, bolts, rules, dividers and plaster casts are strewn about and drawers and shelves are full to overflowing. The den now has pride of place in London’s Science Museum. Though Watt didn’t invent the steam engine – that honour goes to Englishman Thomas Newcomen – his improvements created something twice as powerful and three times as efficient. He teamed up with businessman Matthew Boulton in Birmingham and, from 1774, their Soho Manufactory turned out the engines that powered the Industrial Revolution. By using a separate condenser, the machines’ efficiency grew exponentially. Creating a rotary motion allowed them to run looms, mint coins and hammer iron. Several times a year, Watt’s Smethwick Engine, a giant machine the height of four men, hisses, clunks and creaks into life at the city’s Thinktank science museum. Designed in 1778, it’s the world’s oldest working steam engine and ran constantly for 112 years. Powerful testament to a mechanical genius.

James Watt / The Rocket on display at the Science Museum © National Portrait Gallery, London / Science Museums PL

Robert Stephenson’s Rocket was the premier inter-city locomotive, winning the Rainhill Trials, a competition held 25 years later to choose motive power for the new Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Built in Newcastle, it incorporated important new features, notably a multi-tubular boiler. This enabled its fire to heat water more efficiently, becoming the basis for every steam locomotive built since. It travelled at the remarkable speed of almost thirty miles-per-hour. Robert, born in a cottage near Newcastle in 1803, was the son of pioneering railway and engine builder George Stephenson, with whom he worked closely. On his death, aged just 55, he was buried beside kings and princes at Westminster Abbey and, in his eulogy, was described as ‘the greatest engineer of the present century’. His statue has pride of place outside Euston Station, London’s first railway terminus. You can often see a replica of Rocket in action at the National Railway Museum in York, while the Science Museum has the original.

Fox Talbot outside his photographic studio in Reading, Berkshire, in 1845 © World History Archive / Alamy

Five years after Rocket took to the tracks, a pioneer of photography sealed his place in history. William Henry Fox Talbot created the first permanent negative image, using paper soaked in silver chloride. This was the beginning of the negative/positive process, which he later called ‘calotype’, that became standard in most photography until the age of digital imaging. The oldest surviving negative, exposed in August 1835, pictures an oriel window at his home, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, where he conducted his experiments. Fox Talbot also discovered the use of gallic acid to develop the latent image on exposed film. In 1844 he produced The Pencil of Nature, the first commercial book illustrated entirely by photographs. A hundred years later his descendants gave the house and the surrounding village to the National Trust. Now this beautiful location is often used as a location for period dramas while William and his family rest in the village cemetery.

(Right) The 1835 photo of a window at Fox Talbot's home, Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire came from the world's first negative (left)

A photo of a coachman taken by William Fox Talbot in 1840 at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire where Talbot had his photographic studio. It is the earliest known photograph of a human being on paper.

The Open Door, Fox Talbot, 1843

"The Geologists, Chudleigh, Devon" by William Henry Fox Talbot, 1843

"The Ladder" - William Fox Talbot, April 1844, Wiltshire

Charles Babbage, 1840 © SMSSPL

While Fox Talbot was experimenting with light and chemicals, a contemporary was obsessing over mathematical conundrums.

Charles Babbage, the son of a rich Devon banker, sought a way to eliminate error in complicated calculations. These required the use of printed mathematical tables, which were prone to inaccuracy. Despite working in the mechanical rather than the electronic age, Babbage is regarded as the father of the programmable computer. His inventions were heavy, cumbersome, incredibly complex – and, partly because of this, never completed! His Difference Engine No 1, a calculating machine, would, if completed, have had 25,000 parts, stood eight feet long, seven high and three deep. This was nothing compared to his Analytical Engine. A major intellectual feat of the age, conceived in 1834, it possessed all the features of a basic, modern computer. When the Science Museum built his Difference Engine No 2 from original drawings in 1985, it contained 4,000 moving parts, weighed 2.6 tonnes and worked perfectly. A plaque marks the house in Dorset Street, Marylebone where he lived and worked. His grave of 1871 can be seen in London’s first commercial necropolis, Kensal Green Cemetery.

The world’s one billion television sets owe their existence to a Scot, John Logie Baird, born in 1888 near the River Clyde in Helensburgh. Though the cathode ray tube, which converted electricity into light on a screen, had been invented sometime before, it was Baird who, in London in 1926, first demonstrated his ‘televisor’ – a televised moving image of a person in his attic laboratory at 22 Frith Street, Soho. It hadn’t been easy: earlier experiments in his Hastings laboratory, using a transmitter and receiver created from biscuit tins, penny lenses and string, led to a small explosion, after which his landlord evicted him.

Alexandra Palace © Alex Segre / Alamy

In 1936 an early BBC transmitter, on a hilltop overlooking London at Alexandra Palace, began beaming pictures created on his mechanical, 240-line system. EMI-Marconi’s rival electronic system using 405 lines, trialled simultaneously, ultimately won the day but Baird was the pioneer and went on to invent colour, stereoscopic and big screen television. By the time the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was televised in 1953, the ‘small screen’ was the must-have household gadget. To see some of Baird’s original apparatus in the National Media Museum in Bradford is to return to the exciting early days of grey, flickering ‘pictures by wireless’.

Sir Frank Whittle © Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy

Our final subject, Sir Frank Whittle, was small in stature. It took three attempts and a high-calorie eating regime before the RAF would recruit him – yet he stands tall among British inventors. The Coventry-born creator of the first jet engine was only 22 when he realised that piston-powered flight was yesterday’s technology. While still at flying school in 1929, he designed a gas turbine that could

become a power source for jet thrust, patenting his ‘turbo-jet’ the following year. Unfortunately, the Air Ministry failed to recognise the invention’s potential for speed. It was years before work started on a prototype in Lutterworth, Leicestershire. Eventually, in 1941 at the height of World War II, a test pilot powered his Gloster E28/39 (later the Gloster Meteor) off the runway at RAF Cranwell, Lincolnshire. The age of Allied jet flight had begun. Who knows what life-changing invention a Brit will create next?

The RAF's Gloster Meteor, the Allies' first operational jet aircraft

- See more at: Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture - Fathers of invention

Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture - Fathers of invention

Last edited: