In 2006, Titus Oates was selected by the BBC History Magazine as the 17th century's worst Briton. He ranked the third-equal worst Briton over the last 1000 years (after Jack the Ripper and Thomas Becket).

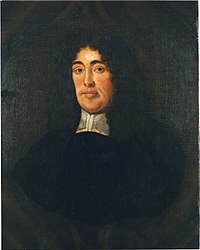

Titus Oates (September 15, 1649 – July 12/13, 1705) was a 17th century perjurer who fabricated a fraudulent Catholic plot to kill King Charles II of England.

Early life

Titus Oates was born in Oakham (the capital of Rutland, England's smallest county) into a family of Baptist clergymen. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and St John's College, Cambridge, and became an Anglican priest but was dismissed due to "drunken blasphemy" and allegations of sodomy (in England in those days, sodomy was a capital offence).

A few months later, he became a curate and Vicar of the parish of Bobbing in Kent. From here he was dismissed for theft, drunkenness, and alleged sodomy.

Royal Navy

In 1677 he got himself appointed as a chaplain of the ship Adventurer in the English navy. He was soon accused of buggery (a capital offence in England at the time) and spared only because of his clergyman's status. Oates fled and temporarily joined the Jesuits.

Jesuits

Oates was involved with the Jesuit houses of St. Omer and Valladolid. Later he claimed that he had pretended to become a Catholic to learn about the secrets of the Jesuits and that before leaving he had heard about a planned Jesuit meeting in London. He later also claimed that he had become a Catholic doctor of Divinity. When he returned to London he befriended the rabid anti-Catholic clergyman Israel Tonge.

The Popish Plot

In August 1678 King Charles was warned of plots against his life, first by Christopher Kirkby, and later by Tonge, whose complex claims included the Jesuits, the English Catholics and King Louis XIV of France. The King was unimpressed but made the mistake of handing the matter over to the anti-Catholic Earl of Danby, who was more willing to listen and who was introduced by Tonge to Oates.

On September 6, 1678 Oates and Tonge approached Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, an Anglican magistrate. Oates claimed that he had a proof of a Catholic plot to assassinate the King and replace him with his Catholic brother James, the Duke of York (future James II). Then all the leading Protestants would be killed.

The King's Council interrogated Oates. On September 28 he made 43 allegations against various members of Catholic religious orders — including 541 Jesuits — and numerous Catholic nobles. He accused Sir George Wakeman, the queen's physician, and Edward Coleman, the secretary to the Duchess of York (Mary of Modena), of planning to assassinate the king. Although Oates probably selected the names randomly or with the help of the Earl of Danby, Coleman was found to have corresponded with a French Jesuit, which condemned him. Wakeman was later acquitted.

Others Oates accused included Dr William Fogarty, Archbishop Peter Talbot of Dublin, Samuel Pepys, and Lord Belasyse. With the help of the Earl of Danby the list grew to 81 accusations. Oates was given a squad of soldiers and he began to round up Jesuits, including those who had helped him in the past.

The Lord Chief Justice, Sir William Scroggs, began a trial against the "Popish Plot". Edward Coleman was sentenced to death on December 3, 1678 for treason and was hanged, drawn and quartered.

On October 12, Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey disappeared for five days and then was found dead in Primrose Hill. He had been strangled and run through with his own sword. Oates exploited this incident to launch a public campaign against the "Papists" and spread a rumor that the murder had been the work of the Jesuits. King Charles heard about the unrest, returned to London and summoned Parliament.

King Charles still did not believe in Titus's accusations. However, Parliament and public opinion forced him to order an investigation. Charles's opponents, who disliked his "Catholic" court and his Catholic wife Catherine of Braganza, exploited the situation. One of the most prominent was Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.

Hysteria continued. Noblewomen carried firearms if they had to venture outdoors at night. Houses were searched for hidden guns — mostly without any significant result. Some Catholic widows tried to ensure their safety by marrying Anglican widowers. The House of Commons was searched — without result — in the expectation of a second Gunpowder Plot being perpetrated.

Oates became more daring and accused five Catholic lords (including Arundel and Bellasyse) for involvement of the plot. The King reputedly laughed at the accusations but the Earl of Shaftesbury had the lords arrested and sent to the Tower. Then Shaftesbury publicly demanded that the King's brother James should be excluded from the royal succession. On November 5, 1678, people burned effigies of the Pope instead of those of Guy Fawkes. At the end of the year the parliament passed a bill, a second Test Act, that excluded Catholics from membership of both Houses.

On November 24, Oates claimed that the Queen was working with the King's physician to poison him and enlisted the aid of "Captain" William Bedloe who was ready to say anything for money. The King personally interrogated Oates, caught him out in a number of inaccuracies and lies and ordered his arrest. However, a couple of days later Parliament forced Oates's release with the threat of constitutional crisis.

Anyone even suspected of being Catholic were driven out of London and forbidden to return within ten miles of the city. Silk armour was produced for fashionable ladies and gentlemen. There was also a playing card set with key figures of the scandal as face cards.

Oates, in turn, received a state apartment in Whitehall and an annual allowance of £1,200. He was not ready to stop, however, and soon presented new allegations. He claimed that assassins intended to shoot the king with silver bullets so the wound would not heal. The public invented its own stories, including a tale that the sound of digging had been heard near the House of Commons and rumours of a French invasion in the Isle of Purbeck. The "purge" spread to the countryside.

Oates was heaped with praise. He asked the College of Arms to check his lineage and produce a coat of arms for him. They gave him the arms of a family that had died out. There were even rumours that Oates was to be married to one of the Earl of Shaftesbury's daughters.

However, public opinion begun to turn against Oates. Having had at least 15 probably innocent men executed, the last Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, executed on July 1, 1681, Judge Scroggs began to declare people innocent. The King began to devise countermeasures.

On August 31, 1681 Oates was told to leave his apartments in Whitehall, but remained undeterred and denounced the King, the Duke of York and just about anyone he regarded as an opponent. He was arrested for sedition, sentenced to a fine of £100,000 and thrown into prison.

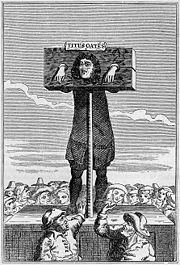

Engraving of a pilloried Titus Oates

When James II acceded to the throne, he had a score to settle. He had Oates retried and sentenced for perjury to annual pillory, loss of clerical dress and imprisonment for life. Oates was taken out of his cell wearing a hat with the text "Titus Oates, convicted upon full evidence of two horrid perjuries" and put into the pillory at the gate of Westminster Hall where passers-by pelted him with eggs. The next day he was pilloried in London and a third day was stripped, tied to a cart and whipped from Aldgate to Newgate. The next day, the whipping resumed. The judge was Judge Jeffreys who stated that Oates was a "Shame to mankind".

Oates spent the next three years in prison. At the accession of William of Orange (King William III) and Mary II in 1688 he was pardoned and granted a pension of £5 a week but his reputation did not significantly recover. The pension was later suspended but in 1698 was restored and increased to £300 a year. Titus Oates died on July 12 or July 13, 1705.

In 2006, Titus Oates was selected by the BBC History Magazine as the 17th century's worst Briton. He ranked the third-equal worst Briton over the last 1000 years.

wikipedia.org