140 years ago this week a group of British redcoats made a heroic stand against the Zulus. Here's a minute by minute account of the action...

Minute by blood-soaked minute, the TRUE story of Zulu: Heart-stopping graphic account of the greatest last stand in British history 140 years ago this week

On January 22, 1879 - 140 years ago - nearly 1,700 British soldiers were massacred by 22,000 Zulu warriors

The British Army had invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control

Fearsome warrior heads for Rorke’s Drift, sparking one of the most famous battles in British history into life

Battle was given the big screen treatment in 1964 starring Michael Caine, Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins

By Jonathan Mayo For The Daily Mail

19 January 2019

Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers, the senior officer at Rorke’s Drift mission station on the border of the Zulu kingdom, is in his tent writing a letter home.

Suddenly his peace is disturbed by two soldiers arriving on horseback, shouting that a British force has been massacred and that thousands of Zulus are heading his way.

It is January 22, 1879 — 140 years ago next week. The British Army, keen to expand its territory in South Africa, has just invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control. Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford, the British commander, boasted: ‘I shall show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power.’

He could not have been more wrong. Twenty-thousand of King Cetshwayo’s men attacked 1,700 British soldiers camped at Isandlwana, and massacred almost all of them.

Now, a huge force of warriors is heading for the tiny Rorke’s Drift encampment, and one of the most famous battles in British history is about to explode into life.

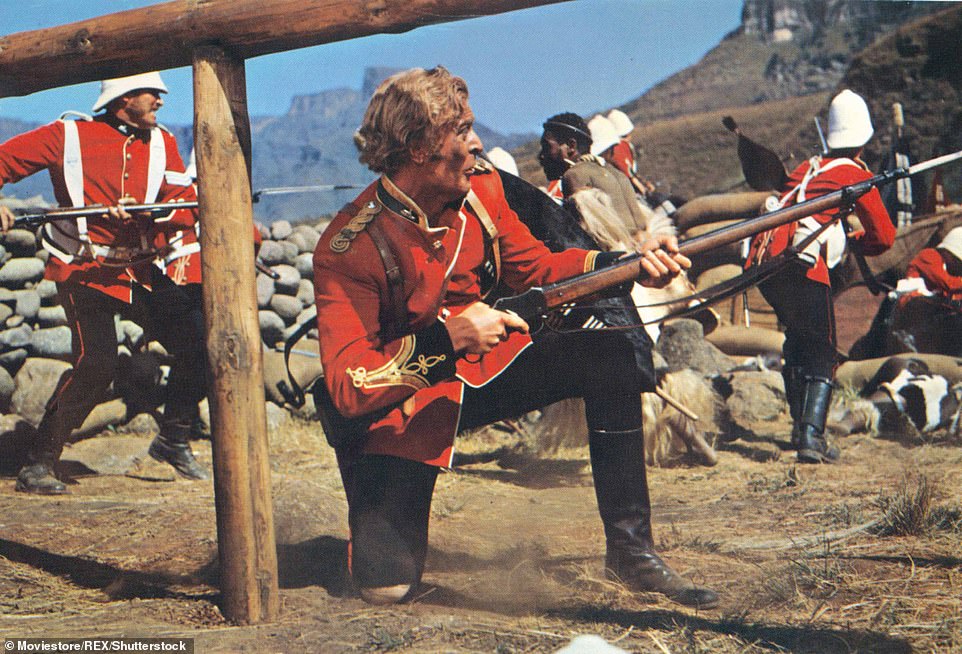

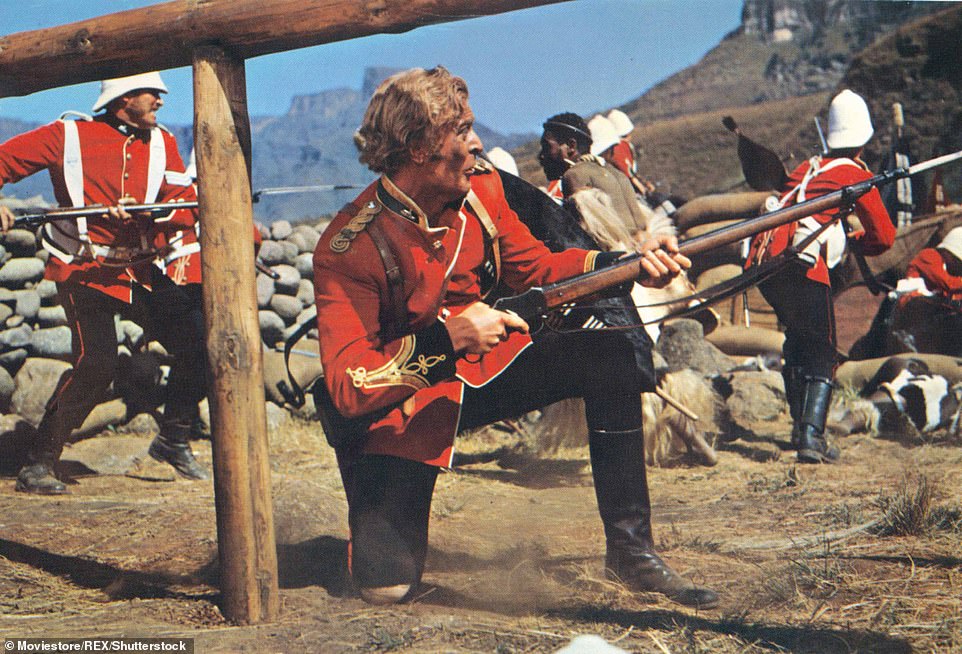

Stanley Baker and Michael Caine star in 1964 film Zulu: It is January 22, 1879 — 140 years ago next week. The British Army, keen to expand its territory in South Africa, has just invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control. Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford, the British commander, boasted: ‘I shall show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power’

Stanley Baker and Michael Caine star in 1964 film Zulu: It is January 22, 1879 — 140 years ago next week. The British Army, keen to expand its territory in South Africa, has just invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control. Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford, the British commander, boasted: ‘I shall show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power’

January 22, 1879

3.45pm

Preparations for the defence of the small, isolated mission station at Rorke’s Drift, six miles from Isandlwana, are under way. A few days ago, Lord Chelmsford’s army turned the one-storey house into a hospital, and the church into a food store. Guarding it is a small force of 104 men from B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, and about 100 local recruits from the Natal Native Contingent (NNC).

Evacuation of the hospital is impossible, so it has been decided to stay and fight. The commanding officer of B Company, 33-year-old Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, has ordered construction of a 4 ft-high perimeter wall around the storehouse and hospital out of sacks of mealie (maize) and heavy wooden biscuit boxes.

The doors to the hospital are being barricaded and holes being made in the walls for troops to fire through. Surgeon James Reynolds looks at the defences with approval. ‘It was charming to find in a short time how protected we had made ourselves’, he wrote later. ‘We felt the mealie barriers might afford us a fair chance.’

Otto Witt, the mission’s Swedish pastor, is distressed to see his wallpaper being ruined and his best furniture scattered on the floor;

the redcoats smile. Fearing for the safety of his wife and children who are staying in a nearby village, Witt rides off to be with them.

A few survivors of Isandlwana are riding past the mission station, giving terrifying accounts of the battle. ‘Not a fighting chance for you, young feller,’ one bedraggled soldier says to a redcoat.

Twenty-thousand of King Cetshwayo’s men attacked 1,700 British soldiers camped at Isandlwana, and massacred almost all of them. Now, a huge force of warriors is heading for the tiny Rorke’s Drift encampment, and one of the most famous battles in British history is about to explode into life (Michael Caine battles a Zulu warrior)

Twenty-thousand of King Cetshwayo’s men attacked 1,700 British soldiers camped at Isandlwana, and massacred almost all of them. Now, a huge force of warriors is heading for the tiny Rorke’s Drift encampment, and one of the most famous battles in British history is about to explode into life (Michael Caine battles a Zulu warrior)

4.20pm

The Zulu regiment heading for Rorke’s Drift is led by King Cetshwayo’s younger brother, Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande. They were the reserve force at Isandlwana and missed out on the battle. Dabulamanzi is determined to plunder the British to have something to show for the victory.

They know Rorke’s Drift from the days when Irishman James Rorke farmed the land. ‘Let us go and have a fight at Jim’s!’ Dabulamanzi’s men shout.

They are formidable and well-disciplined warriors, adept in hand-to-hand combat. Some have rifles, but their chief weapon is the short spear, nicknamed the ‘iklwa’ after the sound it makes when it’s withdrawn from a victim’s body.

The first of Dabulamanzi’s men arrive at the Buffalo River near the mission and are fired on by a mounted unit of the local NNC and their British officer Lieutenant Alfred Henderson. Intimidated by the enemy’s numbers, the NNC turn tail and ride away, followed by Henderson, who shouts his apologies to Lieutenant Chard.

When the remaining NNC soldiers at the mission station see their colleagues fleeing, they leap over the barricades and run, too. Angry at the deserters, some of the men of B Company open fire, shooting a British corporal in the head.

Zulu scouts report back to Prince Dabulamanzi that Rorke’s Drift is poorly defended and full of stores and rifles. Dabulamanzi had not expected such rich pickings.

A painting of the Royal Regiment of Wales, including Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead (centre, left arm raised) at the battle of Rorkes Drift in South Africa, against the Zulu nation

A painting of the Royal Regiment of Wales, including Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead (centre, left arm raised) at the battle of Rorkes Drift in South Africa, against the Zulu nation

4.25pm

The hastily constructed defences at Rorke’s Drift have been built with the expectation that 200 men would be defending them. Now there are only 100.

‘We seemed very few, now all these people had gone,’ Lieutenant Chard wrote later. He orders B Company to build a new barricade, made of biscuit boxes, between the front and rear mealie-bag barricades to serve as a second line of defence in case the Zulus break through. Meanwhile, Private Fred ‘Brickie’ Hitch is clambering on to the thatched roof of the storehouse to act as lookout.

Hitch sees Zulus advancing from behind the mission station and calls down to warn Lieutenant Bromhead, who asks how many there are. ‘About 4,000 to 6,000,’ Hitch reports back.

‘Is that all?’ Bromhead replies, to give his men courage. ‘We can manage that lot very well in a few seconds!’

Michael Caine reloads his rifle amid a battle with the Zulu warriors in the 1964 film about the events of Rorke's Drift

Michael Caine reloads his rifle amid a battle with the Zulu warriors in the 1964 film about the events of Rorke's Drift

4.30pm

Looking through a hole he’s made in the hospital wall, 28-year-old Private Henry Hook watches the Zulu warriors advance at speed as if they expect little resistance.

In the hospital, patients who can walk have been given rifles, and Hook and five other soldiers have each been allocated a small room to defend. ‘You could hardly swing a bayonet in them,’ said Hook.

When the enemy is 500 yards away, Hook and the other defenders on the southern barricade open fire but, to Surgeon Reynolds’s alarm, Dabulamanzi’s men keep on coming ‘at the same slow, slinging trot and all in dead silence’. Finally, the Zulus take cover behind boulders.

In his excitement, 46-year-old Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton, who has been directing the men’s fire, jumps up on a wagon and throws his cap at the enemy.

When the enemy is 500 yards away, Hook and the other defenders on the southern barricade open fire but, to Surgeon Reynolds’s alarm, Dabulamanzi’s men keep on coming ‘at the same slow, slinging trot and all in dead silence’. Finally, the Zulus take cover behind boulders

When the enemy is 500 yards away, Hook and the other defenders on the southern barricade open fire but, to Surgeon Reynolds’s alarm, Dabulamanzi’s men keep on coming ‘at the same slow, slinging trot and all in dead silence’. Finally, the Zulus take cover behind boulders

5pm

There are now Zulus in front as well as behind the mission station. They begin leaping over a garden wall and charging at the British mealie bag barricade.

As the warriors in front are killed, the next wave clamber over their bodies and continue the attack.

Private James Dunbar shoots one of the Zulu leaders dead, so Prince Dabulamanzi takes cover behind a tree 100 yards from the mission station and directs the attacks from there.

5.15pm

Wave after wave of Zulus are hurling themselves at the barricades, but the 22-inch steel bayonets on the end of B Company’s rifles are keeping them out. Nicknamed ‘the lunger’, the bayonets give the British redcoats a reach of more than six feet and they can easily penetrate a shield.

Lookout Fred Hitch has come down from the storehouse rooftop to be in the thick of the action. A Zulu grabs the muzzle of Hitch’s rifle and tries to pull it away. But Hitch has the gun firmly in his left hand: he loads it with his right and shoots the Zulu dead.

5.30pm

Some of Dabulamanzi’s men who have rifles take up positions in caves on a low, flat hill they call Shiyane (‘eyebrow’) behind the mission station. They fire at the backs of the redcoats fighting at the north barricade, but the Zulus’ rifles are ineffective at that range.

Calmly walking up and down behind the British barricades, cheering his men and taking shots at the enemy, is Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton.

A Zulu runs towards the barricade and Dalton shouts: ‘Pot that fellow!’ Seconds later Dalton is hit in the shoulder. He hands his rifle to Lieutenant Chard so calmly that Chard at first has no idea that he is severely wounded.

Surgeon Reynolds drags Dalton towards the storehouse where he and his staff tend to his wound as best they can. Within minutes, Dalton is back on his feet giving orders. Private Henry Hook later described him as ‘one of the bravest men who ever lived’.

6pm

Although only two men have been killed and four injured so far, the defenders of Rorke’s Drift are in danger of being overwhelmed.

Lieutenant Chard orders his men to retreat behind the makeshift wall of biscuit boxes linking the north and south barricades. The Zulus surround the hospital, battering on the barricaded doors and grabbing at the rifles firing through windows and holes in the walls. The men in the hospital must now fend for themselves.

6.20pm

Privates Henry Hook and Thomas Cole are defending a corner room in the hospital, caught ‘like rats in a hole’, in Hook’s words. One patient on a bed begs them to take his bandages off so he can join the fight. Cole, who suffers claustrophobia, panics in the confined space and forces open the outside door. He is immediately shot through the head.

The attackers throw burning spears on to the thatched roof of the hospital and Hook’s room starts to fill with smoke. He has no wish to be burned alive so he slips through an internal door into the next room. The patient in bed begs to come too, but Hook decides it’s impossible.

‘I had to leave him to an awful fate,’ he later confessed. Hook discovers he’s trapped in a room with nine more patients.

6.30pm

There is chaos in other hospital rooms as the Zulus break in through the barricaded doors and overcome the defenders. Private Joseph Williams and the four patients he is guarding are killed.

Meanwhile, Hook is bayoneting and shooting Zulus as they try to get through the internal door. To his relief, he is joined by a private named John Williams who, armed with a pickaxe, starts hacking a hole in the furthest mud wall from the attackers. Williams then drags eight patients though the gap he has made.

The last patient left is Private John Connolly, a large man with a broken leg. Hook crawls through the small hole, grabs Connolly by his coat and pulls him through, breaking his leg once more.

‘As we left the room, the Zulus burst in with furious cries of disappointment and rage,’ Hook said. They lunge at him through the hole. Williams picks up his pickaxe and starts smashing his way into the next room.

6.45pm

Elsewhere in the hospital, Privates William Beckett and John Waters are defending a small room where the missionary Otto Witt keeps his cloak and robes.

Unable to fight any longer, the two men hide in a wardrobe and, fortunately, when the Zulus burst into the room they don’t think to look inside it. For the moment, the two soldiers are safe.

On the barricades, B Company’s chaplain Reverend George Smith is handing out ammunition packets and telling the redcoats: ‘Don’t swear men, but shoot them boys, shoot them.’

Some of the soldiers are ripping apart their jackets and using the cloth to protect their hands from the red-hot rifle barrels.

7.15pm

Hook, Williams and the rest of the survivors in the hospital have reached a room at the far end, closest to their comrades defending the storehouse. The room has a window big enough to get a man through. By the light of the flames from the burning roof, the trapped men can see the biscuit box wall 50 yards away, but the yard is being raked by fire from both sides.

The first man out through the window is an injured trooper named Hunter. Lieutenant Chard watches with horror as Hunter, ‘dazed by the glare of the burning hospital and the firing that was going on all around’, hesitates and a Zulu rushes out and spears him.

Chard urgently calls for two volunteers to help the rest of the trapped men. Private Fred Hitch and Corporal William Allen jump the barricade while their comrades give covering fire. One by one they drag the patients to safety, while inside the hospital Hook and two other soldiers keep the Zulus at bay with only their bayonets, as they have run out of ammunition.

7.45pm

Privates Beckett and Waters are still hiding in the wardrobe. When the room is silent, Beckett runs through an outside door, but is quickly killed.

8pm

All the remaining redcoats and patients in the end room have escaped from the hospital and made it to the safety of the barricade, except for Sergeant Robert Maxfield, who was delirious and refused to move. Private Robert Jones bravely climbs back through the window to try to rescue Maxfield, only to see him killed in his bed by the Zulus.

Private John Waters wraps one of Otto Witt’s black cloaks around him, jumps out of the wardrobe, runs out of the hospital and hides in the grass.

8.30pm

With the hospital burning, and his forces swelled by more warriors who have seen the flames and heard the sound of guns, victory seems to be in Prince Dabulamanzi’s grasp.

He decides to attack the storehouse at the eastern side of the mission station, as far as possible from the fire which illuminates his men and is making them sitting ducks.

Lieutenant Chard knows his situation is getting even worse. He is losing men, and if the storehouse falls they will be surrounded and killed. Chard orders his men to build a temporary 8ft-high fortification, known as a redoubt, out of mealie sacks. It is built in only ten minutes and the wounded are swiftly carried inside. A circle of soldiers is formed within the redoubt. They fire over the heads of the soldiers on the barricades.

9pm

One of Lieutenant Chard’s men lets out a yell: he can see redcoats marching from the direction of Natal. There is cheering as the news spreads and for a few minutes the Zulu attacks cease.

But the men never arrive: when their officers saw the flames, they assumed the station had fallen and ordered their men to return to base.

10pm

Private John Waters is slowly making his way through the grass towards the storehouse. He gets as far as the cookhouse and crawls inside, only to discover it’s full of Zulus firing at his comrades.

As they have their back to him, Waters slowly creeps to the fireplace and stands up in the chimney, remaining as quiet and as still as possible.

January 23, 1879

Midnight

The British have been without water for eight hours, and the injured especially are suffering from acute thirst.

Half-way between the storehouse and the smouldering ruins of the hospital is a water cart. Lieutenant Chard, Private Henry Hook and two others fix their bayonets and run towards the cart, chasing away the Zulus in the yard.

Chard pulls the cart towards the redoubt and pushes a leather hose through a hole in the wall. Containers are filled with the precious river water.

1am

By now both sides are exhausted and the Zulu attacks are becoming less ferocious. Earlier, the Zulus had run 11 miles to Rorke’s Drift and have had little to eat or drink.

Chard and Bromhead have no idea what is going on, so every now and then they climb to the top of the redoubt and listen, keeping what Chard described as ‘an anxious watch’.

3.30am

There is now mostly silence at the mission station, except for the occasional gunshot and the chilling cries of the wounded.

5.20am

As the sun rises, the British can see that the Zulus have gone. Around the mission station are pools of blood, piles of bodies, spears, shields and hundreds of spent cartridges.

A cloud of smoke hangs above the Buffalo River valley and the air is full of the smell of burning wood and flesh. Chard sends some men to retrieve weapons and to kill any wounded or dying Zulus.

Suddenly, a young warrior leaps up and fires at the British at close range, then he jumps a wall and runs away. No one is hit but a volley of shots follows him. ‘I’m glad to say the plucky fellow got off,’ said Chard.

Private John Waters, who had been hiding in the cookhouse fireplace, emerges covered in soot and is almost shot by mistake.

6am

Private Hook walks over to a redcoat who is still looking over the barricade with his rifle at the ready. ‘What are you doing here?’ Hook asks.

When the redcoat doesn’t respond, Hook tilts his helmet back and sees a bullet hole in the dead man’s head.

7am

Concerned that the enemy might return, the British are repairing their barricades and taking the thatch off the storehouse.

Suddenly, vast numbers of Zulus appear from the south-west and sit in the grass, out of range of the British rifles, to watch the redcoats work. Chard calls his men back behind the barricades and orders them to bring any wounded Zulus as a deterrent.

Chard knows he has only a box and a half of ammunition left and they won’t survive another onslaught.

8.00am

After a tense hour, the Zulus get up and walk slowly away. The Rorke’s Drift defenders are mystified until they see a column of men in the distance.

‘Are they friends to relieve us,’ wonders Henry Hook, ‘or more Zulus to destroy us?’ Then, to his relief, he sees British mounted infantry cross the Buffalo River. ‘We gave three cheers, really feeling that it was all right for us,’ Surgeon Reynolds said. The Zulus had no wish to clash with a fresh fighting force.

9.30am

Lieutenant Chard is washing his face in a puddle when Lord Chelmsford, who has just seen the terrible aftermath of the massacre at Isandlwana, arrives. Chelmsford thanks the defenders ‘with much emotion’ for their bravery.

The biscuit boxes that saved many lives are broken open and a makeshift breakfast begins. A barrel of rum has survived the battle and is shared among the men of B Company. To everyone’s surprise, Henry Hook, who is teetotal, holds out his mug for some rum. ‘I feel I want something after all that,’ he says.

Aftermath

It’s estimated that more than 600 Zulus died at Rorke’s Drift, and scores more were killed in brutal reprisals in the days that followed. Just 15 British soldiers were killed in the battle and ten wounded.

The Zulu War continued until the Zulus were defeated in July 1879 at the Battle of Ulundi. For the British, the defence of Rorke’s Drift was a welcome distraction from the disaster of Isandlwana. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli refused to meet Lord Chelmsford, whom he blamed for the defeat, but said that the men of Rorke’s Drift were proof ‘that the stamina and valour of the English soldiery have not diminished’.

An unprecedented 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded, including to Lieutenant Chard, Lieutenant Bromhead, Surgeon James Reynolds, Private Hook and Private Hitch. Chard and Bromhead were invited to dine with Queen Victoria at Balmoral; Bromhead was away fishing so received the invitation too late.

In 1972, the actor Stanley Baker, who played John Chard in the Hollywood blockbuster Zulu, bought Chard’s Victoria Cross at auction for £2,700.

Jonathan Mayo is the author of Titanic Minute By Minute, published by Short Books at £8.99

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6608779/Minute-blood-soaked-minute-TRUE-story-Zulu.html

Minute by blood-soaked minute, the TRUE story of Zulu: Heart-stopping graphic account of the greatest last stand in British history 140 years ago this week

On January 22, 1879 - 140 years ago - nearly 1,700 British soldiers were massacred by 22,000 Zulu warriors

The British Army had invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control

Fearsome warrior heads for Rorke’s Drift, sparking one of the most famous battles in British history into life

Battle was given the big screen treatment in 1964 starring Michael Caine, Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins

By Jonathan Mayo For The Daily Mail

19 January 2019

Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers, the senior officer at Rorke’s Drift mission station on the border of the Zulu kingdom, is in his tent writing a letter home.

Suddenly his peace is disturbed by two soldiers arriving on horseback, shouting that a British force has been massacred and that thousands of Zulus are heading his way.

It is January 22, 1879 — 140 years ago next week. The British Army, keen to expand its territory in South Africa, has just invaded Zululand after the Zulu leader King Cetshwayo refused to accept British control. Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford, the British commander, boasted: ‘I shall show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power.’

He could not have been more wrong. Twenty-thousand of King Cetshwayo’s men attacked 1,700 British soldiers camped at Isandlwana, and massacred almost all of them.

Now, a huge force of warriors is heading for the tiny Rorke’s Drift encampment, and one of the most famous battles in British history is about to explode into life.

January 22, 1879

3.45pm

Preparations for the defence of the small, isolated mission station at Rorke’s Drift, six miles from Isandlwana, are under way. A few days ago, Lord Chelmsford’s army turned the one-storey house into a hospital, and the church into a food store. Guarding it is a small force of 104 men from B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, and about 100 local recruits from the Natal Native Contingent (NNC).

Evacuation of the hospital is impossible, so it has been decided to stay and fight. The commanding officer of B Company, 33-year-old Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, has ordered construction of a 4 ft-high perimeter wall around the storehouse and hospital out of sacks of mealie (maize) and heavy wooden biscuit boxes.

The doors to the hospital are being barricaded and holes being made in the walls for troops to fire through. Surgeon James Reynolds looks at the defences with approval. ‘It was charming to find in a short time how protected we had made ourselves’, he wrote later. ‘We felt the mealie barriers might afford us a fair chance.’

Otto Witt, the mission’s Swedish pastor, is distressed to see his wallpaper being ruined and his best furniture scattered on the floor;

the redcoats smile. Fearing for the safety of his wife and children who are staying in a nearby village, Witt rides off to be with them.

A few survivors of Isandlwana are riding past the mission station, giving terrifying accounts of the battle. ‘Not a fighting chance for you, young feller,’ one bedraggled soldier says to a redcoat.

4.20pm

The Zulu regiment heading for Rorke’s Drift is led by King Cetshwayo’s younger brother, Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande. They were the reserve force at Isandlwana and missed out on the battle. Dabulamanzi is determined to plunder the British to have something to show for the victory.

They know Rorke’s Drift from the days when Irishman James Rorke farmed the land. ‘Let us go and have a fight at Jim’s!’ Dabulamanzi’s men shout.

They are formidable and well-disciplined warriors, adept in hand-to-hand combat. Some have rifles, but their chief weapon is the short spear, nicknamed the ‘iklwa’ after the sound it makes when it’s withdrawn from a victim’s body.

The first of Dabulamanzi’s men arrive at the Buffalo River near the mission and are fired on by a mounted unit of the local NNC and their British officer Lieutenant Alfred Henderson. Intimidated by the enemy’s numbers, the NNC turn tail and ride away, followed by Henderson, who shouts his apologies to Lieutenant Chard.

When the remaining NNC soldiers at the mission station see their colleagues fleeing, they leap over the barricades and run, too. Angry at the deserters, some of the men of B Company open fire, shooting a British corporal in the head.

Zulu scouts report back to Prince Dabulamanzi that Rorke’s Drift is poorly defended and full of stores and rifles. Dabulamanzi had not expected such rich pickings.

4.25pm

The hastily constructed defences at Rorke’s Drift have been built with the expectation that 200 men would be defending them. Now there are only 100.

‘We seemed very few, now all these people had gone,’ Lieutenant Chard wrote later. He orders B Company to build a new barricade, made of biscuit boxes, between the front and rear mealie-bag barricades to serve as a second line of defence in case the Zulus break through. Meanwhile, Private Fred ‘Brickie’ Hitch is clambering on to the thatched roof of the storehouse to act as lookout.

Hitch sees Zulus advancing from behind the mission station and calls down to warn Lieutenant Bromhead, who asks how many there are. ‘About 4,000 to 6,000,’ Hitch reports back.

‘Is that all?’ Bromhead replies, to give his men courage. ‘We can manage that lot very well in a few seconds!’

4.30pm

Looking through a hole he’s made in the hospital wall, 28-year-old Private Henry Hook watches the Zulu warriors advance at speed as if they expect little resistance.

In the hospital, patients who can walk have been given rifles, and Hook and five other soldiers have each been allocated a small room to defend. ‘You could hardly swing a bayonet in them,’ said Hook.

When the enemy is 500 yards away, Hook and the other defenders on the southern barricade open fire but, to Surgeon Reynolds’s alarm, Dabulamanzi’s men keep on coming ‘at the same slow, slinging trot and all in dead silence’. Finally, the Zulus take cover behind boulders.

In his excitement, 46-year-old Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton, who has been directing the men’s fire, jumps up on a wagon and throws his cap at the enemy.

5pm

There are now Zulus in front as well as behind the mission station. They begin leaping over a garden wall and charging at the British mealie bag barricade.

As the warriors in front are killed, the next wave clamber over their bodies and continue the attack.

Private James Dunbar shoots one of the Zulu leaders dead, so Prince Dabulamanzi takes cover behind a tree 100 yards from the mission station and directs the attacks from there.

5.15pm

Wave after wave of Zulus are hurling themselves at the barricades, but the 22-inch steel bayonets on the end of B Company’s rifles are keeping them out. Nicknamed ‘the lunger’, the bayonets give the British redcoats a reach of more than six feet and they can easily penetrate a shield.

Lookout Fred Hitch has come down from the storehouse rooftop to be in the thick of the action. A Zulu grabs the muzzle of Hitch’s rifle and tries to pull it away. But Hitch has the gun firmly in his left hand: he loads it with his right and shoots the Zulu dead.

5.30pm

Some of Dabulamanzi’s men who have rifles take up positions in caves on a low, flat hill they call Shiyane (‘eyebrow’) behind the mission station. They fire at the backs of the redcoats fighting at the north barricade, but the Zulus’ rifles are ineffective at that range.

Calmly walking up and down behind the British barricades, cheering his men and taking shots at the enemy, is Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton.

A Zulu runs towards the barricade and Dalton shouts: ‘Pot that fellow!’ Seconds later Dalton is hit in the shoulder. He hands his rifle to Lieutenant Chard so calmly that Chard at first has no idea that he is severely wounded.

Surgeon Reynolds drags Dalton towards the storehouse where he and his staff tend to his wound as best they can. Within minutes, Dalton is back on his feet giving orders. Private Henry Hook later described him as ‘one of the bravest men who ever lived’.

6pm

Although only two men have been killed and four injured so far, the defenders of Rorke’s Drift are in danger of being overwhelmed.

Lieutenant Chard orders his men to retreat behind the makeshift wall of biscuit boxes linking the north and south barricades. The Zulus surround the hospital, battering on the barricaded doors and grabbing at the rifles firing through windows and holes in the walls. The men in the hospital must now fend for themselves.

6.20pm

Privates Henry Hook and Thomas Cole are defending a corner room in the hospital, caught ‘like rats in a hole’, in Hook’s words. One patient on a bed begs them to take his bandages off so he can join the fight. Cole, who suffers claustrophobia, panics in the confined space and forces open the outside door. He is immediately shot through the head.

The attackers throw burning spears on to the thatched roof of the hospital and Hook’s room starts to fill with smoke. He has no wish to be burned alive so he slips through an internal door into the next room. The patient in bed begs to come too, but Hook decides it’s impossible.

‘I had to leave him to an awful fate,’ he later confessed. Hook discovers he’s trapped in a room with nine more patients.

6.30pm

There is chaos in other hospital rooms as the Zulus break in through the barricaded doors and overcome the defenders. Private Joseph Williams and the four patients he is guarding are killed.

Meanwhile, Hook is bayoneting and shooting Zulus as they try to get through the internal door. To his relief, he is joined by a private named John Williams who, armed with a pickaxe, starts hacking a hole in the furthest mud wall from the attackers. Williams then drags eight patients though the gap he has made.

The last patient left is Private John Connolly, a large man with a broken leg. Hook crawls through the small hole, grabs Connolly by his coat and pulls him through, breaking his leg once more.

‘As we left the room, the Zulus burst in with furious cries of disappointment and rage,’ Hook said. They lunge at him through the hole. Williams picks up his pickaxe and starts smashing his way into the next room.

6.45pm

Elsewhere in the hospital, Privates William Beckett and John Waters are defending a small room where the missionary Otto Witt keeps his cloak and robes.

Unable to fight any longer, the two men hide in a wardrobe and, fortunately, when the Zulus burst into the room they don’t think to look inside it. For the moment, the two soldiers are safe.

On the barricades, B Company’s chaplain Reverend George Smith is handing out ammunition packets and telling the redcoats: ‘Don’t swear men, but shoot them boys, shoot them.’

Some of the soldiers are ripping apart their jackets and using the cloth to protect their hands from the red-hot rifle barrels.

7.15pm

Hook, Williams and the rest of the survivors in the hospital have reached a room at the far end, closest to their comrades defending the storehouse. The room has a window big enough to get a man through. By the light of the flames from the burning roof, the trapped men can see the biscuit box wall 50 yards away, but the yard is being raked by fire from both sides.

The first man out through the window is an injured trooper named Hunter. Lieutenant Chard watches with horror as Hunter, ‘dazed by the glare of the burning hospital and the firing that was going on all around’, hesitates and a Zulu rushes out and spears him.

Chard urgently calls for two volunteers to help the rest of the trapped men. Private Fred Hitch and Corporal William Allen jump the barricade while their comrades give covering fire. One by one they drag the patients to safety, while inside the hospital Hook and two other soldiers keep the Zulus at bay with only their bayonets, as they have run out of ammunition.

7.45pm

Privates Beckett and Waters are still hiding in the wardrobe. When the room is silent, Beckett runs through an outside door, but is quickly killed.

8pm

All the remaining redcoats and patients in the end room have escaped from the hospital and made it to the safety of the barricade, except for Sergeant Robert Maxfield, who was delirious and refused to move. Private Robert Jones bravely climbs back through the window to try to rescue Maxfield, only to see him killed in his bed by the Zulus.

Private John Waters wraps one of Otto Witt’s black cloaks around him, jumps out of the wardrobe, runs out of the hospital and hides in the grass.

8.30pm

With the hospital burning, and his forces swelled by more warriors who have seen the flames and heard the sound of guns, victory seems to be in Prince Dabulamanzi’s grasp.

He decides to attack the storehouse at the eastern side of the mission station, as far as possible from the fire which illuminates his men and is making them sitting ducks.

Lieutenant Chard knows his situation is getting even worse. He is losing men, and if the storehouse falls they will be surrounded and killed. Chard orders his men to build a temporary 8ft-high fortification, known as a redoubt, out of mealie sacks. It is built in only ten minutes and the wounded are swiftly carried inside. A circle of soldiers is formed within the redoubt. They fire over the heads of the soldiers on the barricades.

9pm

One of Lieutenant Chard’s men lets out a yell: he can see redcoats marching from the direction of Natal. There is cheering as the news spreads and for a few minutes the Zulu attacks cease.

But the men never arrive: when their officers saw the flames, they assumed the station had fallen and ordered their men to return to base.

10pm

Private John Waters is slowly making his way through the grass towards the storehouse. He gets as far as the cookhouse and crawls inside, only to discover it’s full of Zulus firing at his comrades.

As they have their back to him, Waters slowly creeps to the fireplace and stands up in the chimney, remaining as quiet and as still as possible.

January 23, 1879

Midnight

The British have been without water for eight hours, and the injured especially are suffering from acute thirst.

Half-way between the storehouse and the smouldering ruins of the hospital is a water cart. Lieutenant Chard, Private Henry Hook and two others fix their bayonets and run towards the cart, chasing away the Zulus in the yard.

Chard pulls the cart towards the redoubt and pushes a leather hose through a hole in the wall. Containers are filled with the precious river water.

1am

By now both sides are exhausted and the Zulu attacks are becoming less ferocious. Earlier, the Zulus had run 11 miles to Rorke’s Drift and have had little to eat or drink.

Chard and Bromhead have no idea what is going on, so every now and then they climb to the top of the redoubt and listen, keeping what Chard described as ‘an anxious watch’.

3.30am

There is now mostly silence at the mission station, except for the occasional gunshot and the chilling cries of the wounded.

5.20am

As the sun rises, the British can see that the Zulus have gone. Around the mission station are pools of blood, piles of bodies, spears, shields and hundreds of spent cartridges.

A cloud of smoke hangs above the Buffalo River valley and the air is full of the smell of burning wood and flesh. Chard sends some men to retrieve weapons and to kill any wounded or dying Zulus.

Suddenly, a young warrior leaps up and fires at the British at close range, then he jumps a wall and runs away. No one is hit but a volley of shots follows him. ‘I’m glad to say the plucky fellow got off,’ said Chard.

Private John Waters, who had been hiding in the cookhouse fireplace, emerges covered in soot and is almost shot by mistake.

6am

Private Hook walks over to a redcoat who is still looking over the barricade with his rifle at the ready. ‘What are you doing here?’ Hook asks.

When the redcoat doesn’t respond, Hook tilts his helmet back and sees a bullet hole in the dead man’s head.

7am

Concerned that the enemy might return, the British are repairing their barricades and taking the thatch off the storehouse.

Suddenly, vast numbers of Zulus appear from the south-west and sit in the grass, out of range of the British rifles, to watch the redcoats work. Chard calls his men back behind the barricades and orders them to bring any wounded Zulus as a deterrent.

Chard knows he has only a box and a half of ammunition left and they won’t survive another onslaught.

8.00am

After a tense hour, the Zulus get up and walk slowly away. The Rorke’s Drift defenders are mystified until they see a column of men in the distance.

‘Are they friends to relieve us,’ wonders Henry Hook, ‘or more Zulus to destroy us?’ Then, to his relief, he sees British mounted infantry cross the Buffalo River. ‘We gave three cheers, really feeling that it was all right for us,’ Surgeon Reynolds said. The Zulus had no wish to clash with a fresh fighting force.

9.30am

Lieutenant Chard is washing his face in a puddle when Lord Chelmsford, who has just seen the terrible aftermath of the massacre at Isandlwana, arrives. Chelmsford thanks the defenders ‘with much emotion’ for their bravery.

The biscuit boxes that saved many lives are broken open and a makeshift breakfast begins. A barrel of rum has survived the battle and is shared among the men of B Company. To everyone’s surprise, Henry Hook, who is teetotal, holds out his mug for some rum. ‘I feel I want something after all that,’ he says.

Aftermath

It’s estimated that more than 600 Zulus died at Rorke’s Drift, and scores more were killed in brutal reprisals in the days that followed. Just 15 British soldiers were killed in the battle and ten wounded.

The Zulu War continued until the Zulus were defeated in July 1879 at the Battle of Ulundi. For the British, the defence of Rorke’s Drift was a welcome distraction from the disaster of Isandlwana. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli refused to meet Lord Chelmsford, whom he blamed for the defeat, but said that the men of Rorke’s Drift were proof ‘that the stamina and valour of the English soldiery have not diminished’.

An unprecedented 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded, including to Lieutenant Chard, Lieutenant Bromhead, Surgeon James Reynolds, Private Hook and Private Hitch. Chard and Bromhead were invited to dine with Queen Victoria at Balmoral; Bromhead was away fishing so received the invitation too late.

In 1972, the actor Stanley Baker, who played John Chard in the Hollywood blockbuster Zulu, bought Chard’s Victoria Cross at auction for £2,700.

Jonathan Mayo is the author of Titanic Minute By Minute, published by Short Books at £8.99

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6608779/Minute-blood-soaked-minute-TRUE-story-Zulu.html