London's Natural History Museum is re-modelling its entrance, moving out its famous Diplodocus skeleton - affectionately known as Dippy - and moving in a blue whale.

The exchange will not happen overnight: the complex logistics involved mean it will be 2017 before the great cetacean is hanging from the ceiling of the iconic Victorian Hintze Hall.

The museum thinks the change will increase the wow factor for visitors.

But it also believes the whale can better convey all the cutting-edge science conducted at the institution.

Museum's 'Dippy' dinosaur makes way for blue whale

By Jonathan Amos, Science correspondent, BBC News

29 January 2015

London's Natural History Museum is re-modelling its entrance, moving out the dinosaur and moving in a blue whale.

An artist's impression of what the world famous museum's entrance will look like once the blue whale skeleton has replaced that of Dippy

The exchange will not happen overnight: the complex logistics involved mean it will be 2017 before the great cetacean is hanging from the ceiling of the iconic Victorian Hintze Hall.

The museum thinks the change will increase the wow factor for visitors.

But it also believes the whale can better convey all the cutting-edge science conducted at the institution.

That is something a plaster-cast model of a Diplodocus skeleton - as familiar and as popular as it has become - can no longer do effectively.

"Everyone loves 'Dippy', but it's just a copy," commented Sir Michael Dixon, the NHM's director, "and what makes this museum special is that we have real objects from the natural world - over 80 million of them - and they enable our scientists and thousands like them from around the world to do real research."

It feels like Dippy the Diplodocus has always guarded the entrance to the Natural History Museum, but in fact it only took up position in the 1970s. The cast was given as a gift by the Scottish American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, after a discussion with King Edward VII, then a keen trustee of the British Museum

It feels like Dippy the Diplodocus has always guarded the entrance to the Natural History Museum, but in fact it only took up position in the 1970s. The cast was given as a gift by the Scottish American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, after a discussion with King Edward VII, then a keen trustee of the British Museum

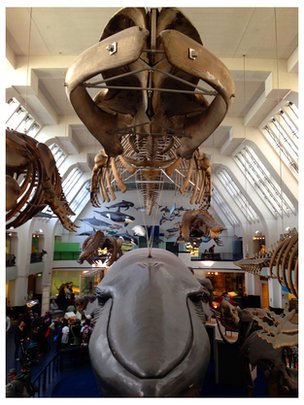

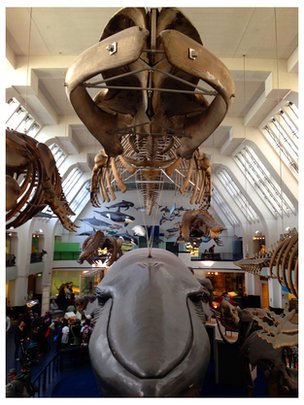

The 82ft-long blue whale skeleton currently hangs in the mammals gallery.

It was acquired for the museum shortly after it opened in 1881. The animal had beached at Wexford on the southeast coast of Ireland (which was then part of the UK).

The curators paid £250 for it in 1891, although it was not put on public display in London until 1935.

Every single bone is present. They will now all be carefully dismantled, cleaned and catalogued, and then re-suspended on wires above the Hintze entrance.

Anyone walking into the current mammals gallery knows the skeleton to have a flat pose, but the intention is to give it a dramatic, diving posture in its new home.

"It's a fantastically complete specimen," said Richard Sabin, whose vertebrates division at the NHM will oversee the transfer.

"It's also one of the largest of its kind on display anywhere in the world; and we know its history, we know how it was killed and processed, and that's quite rare.

"Just the act of moving it will be great for science because we'll scan every bone, and that means any researcher will be able to study it and even print 3D parts if they want to."

The blue whale specimen was acquired by curators shortly after the museum opened. Every single bone is present

The blue whale specimen was acquired by curators shortly after the museum opened. Every single bone is present

The museum has chosen the whale to lead what it calls its "three great narratives".

When the whale is dismantled, every bone will be scanned to make a virtual specimen

These cover the origins and evolution of life, the diversity of life on Earth today, and the long-term sustainability of humans' custodianship of the planet.

The cetacean has something to say on all them, particularly the last. Blue whales - the largest animal that currently lives and the heaviest that we know about to have ever lived - were hunted to the brink of extinction before a ban on their exploitation was put in place in the 1960s.

Indeed, it was NHM scientists who were instrumental in gathering the data in the earlier decades of the 20th Century that showed commercial practices were driving the animal to oblivion.

"And going forward we want to tell more of these stories about the societally relevant research that we do," explained Sir Michael.

"So, for example, today our teams help the police with the forensic examination of crime scenes; we do projects that potentially could help feed nine billion people in 2050; and we also look at whether it's possible to eradicate certain parasitic diseases in Africa.

"We're not just nerdy guys who can identify every species of butterfly."

The museum would like to make the switch-over to the whale much faster, but Hintze Hall is a major circulation space and it has to remain open throughout the transition.

Dippy will not disappear. It is likely to feature in a larger exhibit that illustrates how dinosaurs lived in their environment. This could be taken outside to the front of the South Kensington building, Sir Michael said.

There is also the possibility that Dippy could go on tour as well, to bolster the exhibition spaces at regional museums in the UK.

The entrance in 1901: Whales have held centre stage before. This sperm whale was a long-time incumbent of Hintze Hall

The entrance in 1901: Whales have held centre stage before. This sperm whale was a long-time incumbent of Hintze Hall

But for the larger part of the 20th Century, it was African elephants that dominated the big hall

But for the larger part of the 20th Century, it was African elephants that dominated the big hall

Big undertaking: A bowhead whale skeleton being hoisted into position in the NHM's Whale Hall in 1934

Big undertaking: A bowhead whale skeleton being hoisted into position in the NHM's Whale Hall in 1934

The blue whale will be given a diving posture when it is hung from the ceiling

The blue whale will be given a diving posture when it is hung from the ceiling

London's Natural history Museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology and zoology

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-31025229

The exchange will not happen overnight: the complex logistics involved mean it will be 2017 before the great cetacean is hanging from the ceiling of the iconic Victorian Hintze Hall.

The museum thinks the change will increase the wow factor for visitors.

But it also believes the whale can better convey all the cutting-edge science conducted at the institution.

Museum's 'Dippy' dinosaur makes way for blue whale

By Jonathan Amos, Science correspondent, BBC News

29 January 2015

London's Natural History Museum is re-modelling its entrance, moving out the dinosaur and moving in a blue whale.

An artist's impression of what the world famous museum's entrance will look like once the blue whale skeleton has replaced that of Dippy

The exchange will not happen overnight: the complex logistics involved mean it will be 2017 before the great cetacean is hanging from the ceiling of the iconic Victorian Hintze Hall.

The museum thinks the change will increase the wow factor for visitors.

But it also believes the whale can better convey all the cutting-edge science conducted at the institution.

That is something a plaster-cast model of a Diplodocus skeleton - as familiar and as popular as it has become - can no longer do effectively.

"Everyone loves 'Dippy', but it's just a copy," commented Sir Michael Dixon, the NHM's director, "and what makes this museum special is that we have real objects from the natural world - over 80 million of them - and they enable our scientists and thousands like them from around the world to do real research."

The 82ft-long blue whale skeleton currently hangs in the mammals gallery.

It was acquired for the museum shortly after it opened in 1881. The animal had beached at Wexford on the southeast coast of Ireland (which was then part of the UK).

The curators paid £250 for it in 1891, although it was not put on public display in London until 1935.

Every single bone is present. They will now all be carefully dismantled, cleaned and catalogued, and then re-suspended on wires above the Hintze entrance.

Anyone walking into the current mammals gallery knows the skeleton to have a flat pose, but the intention is to give it a dramatic, diving posture in its new home.

"It's a fantastically complete specimen," said Richard Sabin, whose vertebrates division at the NHM will oversee the transfer.

"It's also one of the largest of its kind on display anywhere in the world; and we know its history, we know how it was killed and processed, and that's quite rare.

"Just the act of moving it will be great for science because we'll scan every bone, and that means any researcher will be able to study it and even print 3D parts if they want to."

The museum has chosen the whale to lead what it calls its "three great narratives".

When the whale is dismantled, every bone will be scanned to make a virtual specimen

These cover the origins and evolution of life, the diversity of life on Earth today, and the long-term sustainability of humans' custodianship of the planet.

The cetacean has something to say on all them, particularly the last. Blue whales - the largest animal that currently lives and the heaviest that we know about to have ever lived - were hunted to the brink of extinction before a ban on their exploitation was put in place in the 1960s.

Indeed, it was NHM scientists who were instrumental in gathering the data in the earlier decades of the 20th Century that showed commercial practices were driving the animal to oblivion.

"And going forward we want to tell more of these stories about the societally relevant research that we do," explained Sir Michael.

"So, for example, today our teams help the police with the forensic examination of crime scenes; we do projects that potentially could help feed nine billion people in 2050; and we also look at whether it's possible to eradicate certain parasitic diseases in Africa.

"We're not just nerdy guys who can identify every species of butterfly."

The museum would like to make the switch-over to the whale much faster, but Hintze Hall is a major circulation space and it has to remain open throughout the transition.

Dippy will not disappear. It is likely to feature in a larger exhibit that illustrates how dinosaurs lived in their environment. This could be taken outside to the front of the South Kensington building, Sir Michael said.

There is also the possibility that Dippy could go on tour as well, to bolster the exhibition spaces at regional museums in the UK.

London's Natural history Museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology and zoology

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-31025229

Last edited: