The 22nd January is the 50th anniversary of a great British war film - Zulu.

The film tells the story of the 22nd January 1879 Battle of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War during which just 150 British troops resolutely and successfully defended their garrison against an intense assault by 3,000 to 4,000 Zulu warriors.

What gives the film its appeal is that, unlike many films today, it is completely unblighted by political correctness and swaggering, arrogant Yanks. It is filled by great British actors like Michael Caine, Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins playing great British heroes. Not a Yank in sight.

Had Zulu been made today it would overflow with anti-colonial barbs and damaging denunciations of British savagery

Also, Hollywood at the time was insisting on catapulting Americans into OUR war films. The real-life World War II British commandos whose exploits inspired The Guns Of Navarone (1961) somehow needed the help of Gregory Peck, while Steve McQueen and James Garner were incongruous inmates of a British prisoner-of-war camp in The Great Escape (1963). In real life, however, no Americans whatsoever took part in the Great Escape.

It would get worse, with whole episodes of Britain’s wars regularly hijacked and Americanised in a way that left British viewers grumbling into their beer about blatant misportrayals of our past.

Even Zulu Dawn, Zulu’s 1979 successor about another battle on the eve of Rorke’s Drift, found a top-of-the-bill role for an imported Burt Lancaster.

But Zulu itself stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story.

A spell-binding story of raw courage with NO gore, NO political correctness and NO swaggering Yanks... on its 50th anniversary, a salute to Zulu, a great British war film

By Tony Rennell

2 January 2014

Daily Mail

The battle is re-fought like no other single incident in Britain’s imperial history. It reappears regularly on television, particularly at high days and holidays. This festive season is no exception.

On our screens, the desperate fight by 140 soldiers to defend Rorke’s Drift, a tiny outpost of Queen Victoria’s empire in the South African veldt in 1879, was re-enacted in that classic British war film, Zulu.

Once again, our blood chilled at the fast-approaching rumble of fists pounding on cowhide shields.

Best of enemies: Lt Bromhead (Michael Caine) clashes with a Zulu warrior in the 1964 epic

‘Damn funny,’ is the young British lieutenant’s quizzical remark as he looks towards the empty horizon, ‘like a train in the distance . . .’

Then up goes an anguished cry as the enemy suddenly materialises in a vast mass on the surrounding hilltops — ‘Blimey … Zulus … Thousands of ’em …!’

Introducing Michael Caine: The actor, now in his 80s, led an all British cast

And so the action begins in a film universally (and rightly) hailed for its epic battle scenes and unsurpassed on-screen adventure.

The outcome never changes, but its impact is never dulled as wave after wave of black warriors heroically hurl themselves at barricades manned just as heroically by white men in scarlet tunics and gleaming white pith helmets.

The defenders — outnumbered by more than 25 to one against 4,000 Zulus — fall back, regroup, hold their ground, fight their attackers hand-to-hand to a standstill, and win the day, but only just.

The Zulus finally withdraw, but not before delivering a haunting song in tribute to the courage of the Britons.

Despite the terrible bloodshed, there is honour on both sides — and a lump in the throats of those of us watching this masterpiece of British film-making even for the umpteenth time.

Zulu has the power to grip our attention because it is timeless in theme, look and style — which makes it even more of a surprise that it is half a century old and this month celebrates its 50th birthday.

It opened at the Plaza in Lower Regent Street, London, on January 22, 1964 — the 85th anniversary of the battle it depicted.

Today it is still as fresh as it was for that premiere audience, its wide-screen images of the majestic South African landscape as stunning as ever, its action-packed fight scenes compelling, its human drama absorbing. The cobwebs show only in the opening credit that reads: ‘And introducing Michael Caine.’

Playing Bromhead, one of the two lieutenants who commanded the Rorke’s Drift defence, shot the then little-known Caine into the big time.

He is in his 80s now, with more than 100 films to his credit, but Zulu remains among his most memorable (even if his role as a toff officer was a far cry from the Cockney Jack-the-lad he proved better suited to).

Caine was part of an all-British cast, led by the magnificent home-grown talents of Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins.

Action: The all-British cast was led by the magnificent home-grown talents of Stanley Baker (pictured) and Jack Hawkins

Richard Burton’s voice thundered out the narration. This in itself was noteworthy.

Elsewhere, Hollywood was insisting on catapulting Americans into our war films. The British commandos whose exploits inspired The Guns Of Navarone (1961) somehow needed the help of Gregory Peck, while Steve McQueen and James Garner were incongruous inmates of a British prisoner-of-war camp in The Great Escape (1963).

It would get worse, with whole episodes of Britain’s wars regularly hijacked and Americanised in a way that left British viewers grumbling into their beer about blatant misportrayals of our past.

Even Zulu Dawn, Zulu’s 1979 successor about another battle on the eve of Rorke’s Drift, found a top-of-the-bill role for an imported Burt Lancaster.

But Zulu itself stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story.

It helped that director Cy Endfield had been forced out of his American homeland. Blacklisted by Hollywood in the Red-baiting Fifties because of alleged communist sympathies, he found refuge in the United Kingdom.

One of the many memorable battle scenes as the hopelessly outnumbered British take on wave after wave of Zulu warriors

Amazingly, the film he co-produced with its lead actor, Baker, manages to remain neutral about Britain’s much-maligned imperial heritage.

I can’t help thinking that a modern re-make of Zulu would overflow with anti-colonial barbs and damaging denunciations of British savagery — not least because the Zulu War of 1879 was, in truth, one of the darker chapters of our imperial history, an unedifying episode of land-grabbing for the sake of it and military intervention for no good reason.

An excuse was invented to invade Zululand and an easy victory expected. But 1,300 men of the first column to enter were cut to pieces at Isandlwana.

The British retreated in disarray, and the victorious Zulus marched forward to menace the borders of British South Africa, only to be stopped heroically at Rorke’s Drift.

When the news of both battles reached Britain, national celebration of the smaller victory was cynically used to dilute the bigger catastrophe, an attempted cover-up worthy of government spin-doctors a century and more later.

Ready, aim, fire! Stanley Baker commands a group of British soldiers

Yet Zulu thankfully avoids taking sides in this moral morass. It doesn’t play on manufactured guilt, or lecture and hector us from some anachronistic ethical high ground. It avoids self-righteous, self-serving politics and pays pure and simple tribute to human endeavour.

The moment that, for me, elevates it into a different dimension is when a young British soldier stares open-mouthed at the huge enemy army encircling Rorke’s Drift. The situation looks hopeless, and death — skewered agonisingly in the dust — a certainty.

‘Why does it have to be us?’ he wails. ‘Why us?’

The handlebar-moustachioed colour sergeant next to him, erect and unflinching, could have replied with windy patriotic zeal and flag-waving imperialist grandeur.

Instead, this paragon of British backbone — played incomparably by Nigel Green — says calmly: ‘Because we’re here, lad. Just us. Nobody else.’

His is the authentic voice of soldiering through the centuries — as true today for our troops in Afghanistan as it was for Queen Victoria’s footsoldiers. Men doing their duty, facing death because that’s their job. No hint of glory. No pleasure in killing.

British grit holds out against hopeless odds, and defeat is turned to triumph of a sort. But war, we conclude, is always terrible, an evil — if sometimes a necessary one.

And there is a price to pay for the victors as well as the defeated. As the smoke of guns disperses over the final battle scene, the British soldiers stare in horror at the piled-up bodies of Zulu around their sand-bagged last redoubt.

They are not triumphant but appalled at the ‘butcher’s yard’ — as Lt Chard (Stanley Baker) puts it — which they have inflicted. ‘I feel sick,’ says Lt Bromhead (Caine), ‘and ashamed.’

Zulu stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story

And it’s that mood that sets Zulu apart from run-of-the-mill war films. It tells us that we can and should loathe war on principle, but still salute those we send to fight on our behalf.

That message makes it as moving and thought-provoking now as it was when first released five decades ago.

It has not dated or tired or lost its potency — which is all the more remarkable given that it is the product of an era almost unrecognisable now, as the circumstances in which it was made demonstrate.

Filming was on location in a deeply racist South Africa, where apartheid was ruthlessly enforced by a whites-only minority government. The African National Congress was a banned organisation and Nelson Mandela on trial for treason.

His 27 years in prison had just begun. The idea that one day he would be his country’s leader and the world’s inspiration was unthinkable.

Though the outside world voiced disapproval of apartheid, it had not yet made South Africa the pariah state it would soon become, boycotted and out-of-bounds.

Thus, the Labour-supporting actor Baker and Left-leaning fellow producer Endfield were not deterred from filming there — though they chafed at the racist rules they found imposed on them when they arrived.

Cast and crew were warned that having sex with non-whites was illegal and would result in prosecution, imprisonment and a lashing.

The producers were also forbidden from paying wages to the 500 local black men and women they used as extras for the Zulu army — a stricture they got round by giving them the herd of cattle used on set.

But this was a country whose black population was so held back that those extras had never seen a film, and had no idea what they were being asked to do.

To enlighten them, Endfield put on the screening of a Western out there in the remote Drakensberg Mountains. Surprisingly perhaps, the South African government showed no qualms at allowing film-makers with such liberal credentials into their own backyard.

Lt Bromhead (Caine) tends to an injured Lt Chard (Stanley Baker) in another memorable scene

Presumably they were comfort-able with the notion of a film in which a minority of white men held out against an overwhelming number of blacks.

On the face of it, the events at Rorke’s Drift mirrored the white supremacists’ view of the world.

Yet Baker and Endfield’s film is the exact opposite. It soars above racial stereotypes. The Zulus are presented as a disciplined, proud and honourable people, of equal worth, not the sub-species that apartheid ideology reduced them to.

A single British redcoat’s sneering remark on screen that ‘they’re savages, aren’t they’ (the actual Victorian view, in all honesty) is rapidly countered with an outpouring of respect for their bravery.

No wonder this was a film the South African government made sure its black population would never get to see for themselves. Meanwhile, in the UK, Zulu opened to considerable acclaim, though its historical imperfections did not go unnoticed.

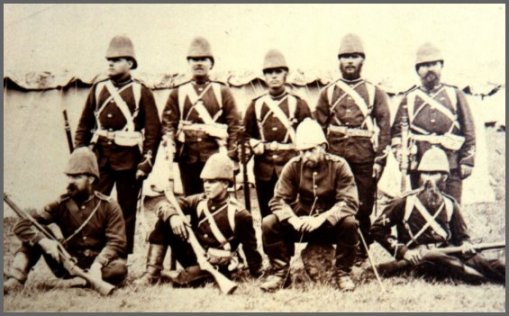

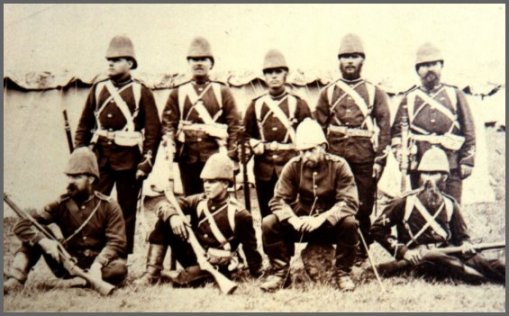

Some of the real-life heroes of Rorke's Drift. The 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot

One private soldier, Henry Hook, is depicted as a malingerer and a drunk who finally comes good and does his duty — a dramatic device invented for the screenplay.

The real Hook’s ageing daughter left the premiere in disgust when she saw her model soldier father’s reputation trashed.

There are other errors of detail. Pedants point out that some of the rifles are the wrong vintage or the wrong make.

The regiment fighting at Rorke’s Drift is described as the South Wales Borders, whereas military historians know it was the 2nd Warwickshire, which did not become a Welsh regiment until two years after the battle.

The Zulus’ final haunting song saluting ‘fellow braves’ did not happen, any more than a stirring rendition of Men Of Harlech sounded out in wonderful Welsh baritones from the barricades.

A bigger discrepancy is the absence of gore. No guts are spilled. Fatal stab wounds are like pinpricks. Bodies lie intact despite the bone-crunching, stomach-churning effect of bullets and bayonets. ‘It is war without the nasty bits,’ wrote one military specialist.

But this was typical of the times. Back in the early Sixties, film- makers and censors thankfully spared us graphic violence. A few years after Zulu, this restraint came off when Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) deliberately introduced more realism into cinematic slaughter.

There was no looking back after that — or, for the squeamish among us, no looking at all. A remake of Zulu today would be drenched in so much blood it might prove unwatchable.

Yet the absence of gore, far from diminishing Zulu, adds to its greatness. If it homed in on the visual horrors of war, it would detract from what one critic called ‘the iconic mix of ripping yarn and derring-do’, the story of Rorke’s Drift, where 11 VCs were won for valour and a timeless legend was born.

They don’t make films like Zulu any more, more’s the pity.

But, please, movie-makers, don’t try to update it. I suspect a modern version would torture itself (and its viewers) with political correctness and overload it (and us) with battlefield bloodletting and special effects, all in 3D, in-your-face technology and ear-splitting multi-channel sound.

No thank you. I’ll stick with the classic we know and love — half a century old but still going strong.

Zulu is on Channel 4 tomorrow at 1.15pm.

Read more: A salute to Zulu: A spell binding story of raw courage with NO gore, NO political correctness and NO swaggering Yanks... a great British war film on its 50th anniversary | Mail Online

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

The film tells the story of the 22nd January 1879 Battle of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War during which just 150 British troops resolutely and successfully defended their garrison against an intense assault by 3,000 to 4,000 Zulu warriors.

What gives the film its appeal is that, unlike many films today, it is completely unblighted by political correctness and swaggering, arrogant Yanks. It is filled by great British actors like Michael Caine, Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins playing great British heroes. Not a Yank in sight.

Had Zulu been made today it would overflow with anti-colonial barbs and damaging denunciations of British savagery

Also, Hollywood at the time was insisting on catapulting Americans into OUR war films. The real-life World War II British commandos whose exploits inspired The Guns Of Navarone (1961) somehow needed the help of Gregory Peck, while Steve McQueen and James Garner were incongruous inmates of a British prisoner-of-war camp in The Great Escape (1963). In real life, however, no Americans whatsoever took part in the Great Escape.

It would get worse, with whole episodes of Britain’s wars regularly hijacked and Americanised in a way that left British viewers grumbling into their beer about blatant misportrayals of our past.

Even Zulu Dawn, Zulu’s 1979 successor about another battle on the eve of Rorke’s Drift, found a top-of-the-bill role for an imported Burt Lancaster.

But Zulu itself stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story.

A spell-binding story of raw courage with NO gore, NO political correctness and NO swaggering Yanks... on its 50th anniversary, a salute to Zulu, a great British war film

By Tony Rennell

2 January 2014

Daily Mail

The battle is re-fought like no other single incident in Britain’s imperial history. It reappears regularly on television, particularly at high days and holidays. This festive season is no exception.

On our screens, the desperate fight by 140 soldiers to defend Rorke’s Drift, a tiny outpost of Queen Victoria’s empire in the South African veldt in 1879, was re-enacted in that classic British war film, Zulu.

Once again, our blood chilled at the fast-approaching rumble of fists pounding on cowhide shields.

Best of enemies: Lt Bromhead (Michael Caine) clashes with a Zulu warrior in the 1964 epic

‘Damn funny,’ is the young British lieutenant’s quizzical remark as he looks towards the empty horizon, ‘like a train in the distance . . .’

Then up goes an anguished cry as the enemy suddenly materialises in a vast mass on the surrounding hilltops — ‘Blimey … Zulus … Thousands of ’em …!’

Introducing Michael Caine: The actor, now in his 80s, led an all British cast

And so the action begins in a film universally (and rightly) hailed for its epic battle scenes and unsurpassed on-screen adventure.

The outcome never changes, but its impact is never dulled as wave after wave of black warriors heroically hurl themselves at barricades manned just as heroically by white men in scarlet tunics and gleaming white pith helmets.

The defenders — outnumbered by more than 25 to one against 4,000 Zulus — fall back, regroup, hold their ground, fight their attackers hand-to-hand to a standstill, and win the day, but only just.

The Zulus finally withdraw, but not before delivering a haunting song in tribute to the courage of the Britons.

Despite the terrible bloodshed, there is honour on both sides — and a lump in the throats of those of us watching this masterpiece of British film-making even for the umpteenth time.

Zulu has the power to grip our attention because it is timeless in theme, look and style — which makes it even more of a surprise that it is half a century old and this month celebrates its 50th birthday.

It opened at the Plaza in Lower Regent Street, London, on January 22, 1964 — the 85th anniversary of the battle it depicted.

Today it is still as fresh as it was for that premiere audience, its wide-screen images of the majestic South African landscape as stunning as ever, its action-packed fight scenes compelling, its human drama absorbing. The cobwebs show only in the opening credit that reads: ‘And introducing Michael Caine.’

Playing Bromhead, one of the two lieutenants who commanded the Rorke’s Drift defence, shot the then little-known Caine into the big time.

He is in his 80s now, with more than 100 films to his credit, but Zulu remains among his most memorable (even if his role as a toff officer was a far cry from the Cockney Jack-the-lad he proved better suited to).

Caine was part of an all-British cast, led by the magnificent home-grown talents of Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins.

Action: The all-British cast was led by the magnificent home-grown talents of Stanley Baker (pictured) and Jack Hawkins

Richard Burton’s voice thundered out the narration. This in itself was noteworthy.

Elsewhere, Hollywood was insisting on catapulting Americans into our war films. The British commandos whose exploits inspired The Guns Of Navarone (1961) somehow needed the help of Gregory Peck, while Steve McQueen and James Garner were incongruous inmates of a British prisoner-of-war camp in The Great Escape (1963).

It would get worse, with whole episodes of Britain’s wars regularly hijacked and Americanised in a way that left British viewers grumbling into their beer about blatant misportrayals of our past.

Even Zulu Dawn, Zulu’s 1979 successor about another battle on the eve of Rorke’s Drift, found a top-of-the-bill role for an imported Burt Lancaster.

But Zulu itself stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story.

It helped that director Cy Endfield had been forced out of his American homeland. Blacklisted by Hollywood in the Red-baiting Fifties because of alleged communist sympathies, he found refuge in the United Kingdom.

One of the many memorable battle scenes as the hopelessly outnumbered British take on wave after wave of Zulu warriors

Amazingly, the film he co-produced with its lead actor, Baker, manages to remain neutral about Britain’s much-maligned imperial heritage.

I can’t help thinking that a modern re-make of Zulu would overflow with anti-colonial barbs and damaging denunciations of British savagery — not least because the Zulu War of 1879 was, in truth, one of the darker chapters of our imperial history, an unedifying episode of land-grabbing for the sake of it and military intervention for no good reason.

An excuse was invented to invade Zululand and an easy victory expected. But 1,300 men of the first column to enter were cut to pieces at Isandlwana.

The British retreated in disarray, and the victorious Zulus marched forward to menace the borders of British South Africa, only to be stopped heroically at Rorke’s Drift.

When the news of both battles reached Britain, national celebration of the smaller victory was cynically used to dilute the bigger catastrophe, an attempted cover-up worthy of government spin-doctors a century and more later.

Ready, aim, fire! Stanley Baker commands a group of British soldiers

Yet Zulu thankfully avoids taking sides in this moral morass. It doesn’t play on manufactured guilt, or lecture and hector us from some anachronistic ethical high ground. It avoids self-righteous, self-serving politics and pays pure and simple tribute to human endeavour.

The moment that, for me, elevates it into a different dimension is when a young British soldier stares open-mouthed at the huge enemy army encircling Rorke’s Drift. The situation looks hopeless, and death — skewered agonisingly in the dust — a certainty.

‘Why does it have to be us?’ he wails. ‘Why us?’

The handlebar-moustachioed colour sergeant next to him, erect and unflinching, could have replied with windy patriotic zeal and flag-waving imperialist grandeur.

Instead, this paragon of British backbone — played incomparably by Nigel Green — says calmly: ‘Because we’re here, lad. Just us. Nobody else.’

His is the authentic voice of soldiering through the centuries — as true today for our troops in Afghanistan as it was for Queen Victoria’s footsoldiers. Men doing their duty, facing death because that’s their job. No hint of glory. No pleasure in killing.

British grit holds out against hopeless odds, and defeat is turned to triumph of a sort. But war, we conclude, is always terrible, an evil — if sometimes a necessary one.

And there is a price to pay for the victors as well as the defeated. As the smoke of guns disperses over the final battle scene, the British soldiers stare in horror at the piled-up bodies of Zulu around their sand-bagged last redoubt.

They are not triumphant but appalled at the ‘butcher’s yard’ — as Lt Chard (Stanley Baker) puts it — which they have inflicted. ‘I feel sick,’ says Lt Bromhead (Caine), ‘and ashamed.’

Zulu stuck resolutely to its historical integrity, one of the last blockbusters of its kind to dare to exclude American stars from what was essentially a British story

And it’s that mood that sets Zulu apart from run-of-the-mill war films. It tells us that we can and should loathe war on principle, but still salute those we send to fight on our behalf.

That message makes it as moving and thought-provoking now as it was when first released five decades ago.

It has not dated or tired or lost its potency — which is all the more remarkable given that it is the product of an era almost unrecognisable now, as the circumstances in which it was made demonstrate.

Filming was on location in a deeply racist South Africa, where apartheid was ruthlessly enforced by a whites-only minority government. The African National Congress was a banned organisation and Nelson Mandela on trial for treason.

His 27 years in prison had just begun. The idea that one day he would be his country’s leader and the world’s inspiration was unthinkable.

Though the outside world voiced disapproval of apartheid, it had not yet made South Africa the pariah state it would soon become, boycotted and out-of-bounds.

Thus, the Labour-supporting actor Baker and Left-leaning fellow producer Endfield were not deterred from filming there — though they chafed at the racist rules they found imposed on them when they arrived.

Cast and crew were warned that having sex with non-whites was illegal and would result in prosecution, imprisonment and a lashing.

The producers were also forbidden from paying wages to the 500 local black men and women they used as extras for the Zulu army — a stricture they got round by giving them the herd of cattle used on set.

But this was a country whose black population was so held back that those extras had never seen a film, and had no idea what they were being asked to do.

To enlighten them, Endfield put on the screening of a Western out there in the remote Drakensberg Mountains. Surprisingly perhaps, the South African government showed no qualms at allowing film-makers with such liberal credentials into their own backyard.

Lt Bromhead (Caine) tends to an injured Lt Chard (Stanley Baker) in another memorable scene

Presumably they were comfort-able with the notion of a film in which a minority of white men held out against an overwhelming number of blacks.

On the face of it, the events at Rorke’s Drift mirrored the white supremacists’ view of the world.

Yet Baker and Endfield’s film is the exact opposite. It soars above racial stereotypes. The Zulus are presented as a disciplined, proud and honourable people, of equal worth, not the sub-species that apartheid ideology reduced them to.

A single British redcoat’s sneering remark on screen that ‘they’re savages, aren’t they’ (the actual Victorian view, in all honesty) is rapidly countered with an outpouring of respect for their bravery.

No wonder this was a film the South African government made sure its black population would never get to see for themselves. Meanwhile, in the UK, Zulu opened to considerable acclaim, though its historical imperfections did not go unnoticed.

Some of the real-life heroes of Rorke's Drift. The 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot

One private soldier, Henry Hook, is depicted as a malingerer and a drunk who finally comes good and does his duty — a dramatic device invented for the screenplay.

The real Hook’s ageing daughter left the premiere in disgust when she saw her model soldier father’s reputation trashed.

There are other errors of detail. Pedants point out that some of the rifles are the wrong vintage or the wrong make.

The regiment fighting at Rorke’s Drift is described as the South Wales Borders, whereas military historians know it was the 2nd Warwickshire, which did not become a Welsh regiment until two years after the battle.

The Zulus’ final haunting song saluting ‘fellow braves’ did not happen, any more than a stirring rendition of Men Of Harlech sounded out in wonderful Welsh baritones from the barricades.

A bigger discrepancy is the absence of gore. No guts are spilled. Fatal stab wounds are like pinpricks. Bodies lie intact despite the bone-crunching, stomach-churning effect of bullets and bayonets. ‘It is war without the nasty bits,’ wrote one military specialist.

But this was typical of the times. Back in the early Sixties, film- makers and censors thankfully spared us graphic violence. A few years after Zulu, this restraint came off when Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) deliberately introduced more realism into cinematic slaughter.

There was no looking back after that — or, for the squeamish among us, no looking at all. A remake of Zulu today would be drenched in so much blood it might prove unwatchable.

Yet the absence of gore, far from diminishing Zulu, adds to its greatness. If it homed in on the visual horrors of war, it would detract from what one critic called ‘the iconic mix of ripping yarn and derring-do’, the story of Rorke’s Drift, where 11 VCs were won for valour and a timeless legend was born.

They don’t make films like Zulu any more, more’s the pity.

But, please, movie-makers, don’t try to update it. I suspect a modern version would torture itself (and its viewers) with political correctness and overload it (and us) with battlefield bloodletting and special effects, all in 3D, in-your-face technology and ear-splitting multi-channel sound.

No thank you. I’ll stick with the classic we know and love — half a century old but still going strong.

Zulu is on Channel 4 tomorrow at 1.15pm.

Read more: A salute to Zulu: A spell binding story of raw courage with NO gore, NO political correctness and NO swaggering Yanks... a great British war film on its 50th anniversary | Mail Online

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

Last edited: