Today is 800 years exactly since one of England's most reviled monarchs, King John, died from dysentery. BBC News examines how this gut-wrenching condition has claimed the lives of several English kings, changing the course of history.

King John: Dysentery and the death that changed history

By Greig Watson

BBC News

19 October 2016

The ruin of Newark Castle in Nottinghamshire, where John died, possibly in the gatehouse on the far left

It is 800 years since one of England's most reviled monarchs, King John, died from dysentery. BBC News examines how this gut-wrenching condition has claimed the lives of several English kings, changing the course of history.

"Foul as it is, Hell itself is made fouler by the presence of John."

Chronicler Matthew Paris's epitaph reflects the contempt with which John was widely held - but could also be a nod to his unpleasant demise.

His chaotic and disastrous reign came to a heaving end on, or near, the toilet. Or whatever served as a toilet in Newark Castle on 19 October 1216.

By finishing John, dysentery - essentially diarrhoea so violent it causes bleeding and death - may have spectacularly changed the course of English history.

John was blamed for the murder of Prince Arthur, his nephew, who had a better claim to the throne

And it was not the only time it managed to kill a king or set the country on a new course.

"He was a total jerk," says Marc Morris, author of King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta.

"He was loathed by contemporaries as cruel and cowardly.

"Many people think of medieval Europe as a place where anything goes, like Game of Thrones.

"But there were rules, especially about how you treated nobles. John broke these taboos.

"He didn't just kill, he was sadistic. He starved people to death. And not just enemy knights, but once a rival's wife and son."

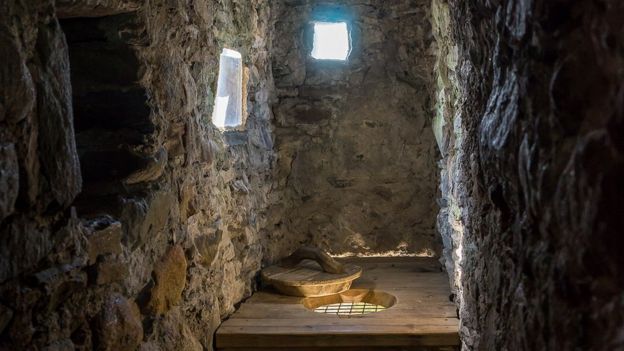

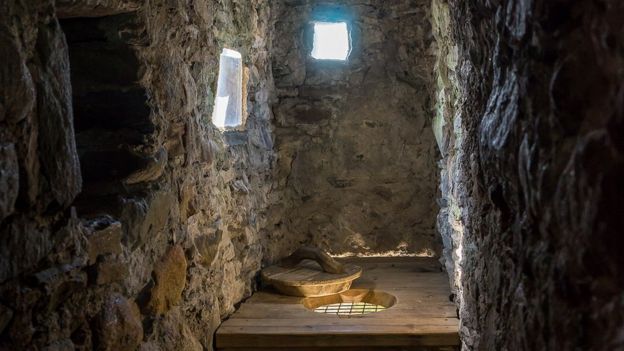

Medieval sanitary arrangements could be basic, even for the aristocracy in their castles

Losing swathes of inherited territory in France, and then pushing up taxes to fund vain attempts to get it back, alienated his subjects in England.

A reputation for being a sexual predator with the wives and daughters of nobles, along with arbitrary treatment of both allies and rivals, angered the elite.

He annoyed Pope Innocent III so much the pontiff excommunicated John and ordered England's churches closed.

All this led to civil war, Magna Carta and a French prince, Louis, being offered the throne.

A fanciful recreation of John being forced to approve the Magna Carta

But while fighting, John became weak and sick. Travelling from Norfolk towards the Midlands, he halted at Newark and soon after died.

Rumours put his demise down to eating unripe peaches, drinking too much sweet ale or even being dosed with poison from a toad.

Dr Iona McCleery, an expert in medieval medicine, says: "To say John died of overindulgence was a way of criticising his personality. It implies intemperance, gluttony and imprudence.

"To say he was poisoned showed he was hated. Whatever the truth, those writing down history had nothing good to say about John."

Dysentery is caused by parasites in the gut but is also easily confused with other viral and bacterial infections.

Despite civil war King John managed to get a royal tomb in Worcester Cathedral

It is most commonly spread by dirty water or food being contaminated with human waste.

Dr McCleery says: "Dysentery was not necessarily a condition of the commoner. Lots of vegetables were grown in soil fertilised with human waste.

"John had been on the march, fighting a war, under a lot of strain.

"He was probably physically and emotionally exhausted and living conditions on the march can be primitive, no matter who you are."

After John's death the fire went out of the civil war and Prince Louis was chased from England. Stability returned, the Magna Carta took root.

But dysentery was not finished with the fate of England or its kings.

Henry V was poised to become king of France but died on campaign, leaving an infant heir

Edward I, the Hammer of the Scots, died of it on his way to renew war with Robert the Bruce in 1307. His son Edward II lost the resulting battles and Scotland retained its independence.

It may have accounted for Edward, the Black Prince. Famed warrior and statesman, his death in 1376 the year before his father Edward III meant the Black Prince's son, Richard II, would became king aged 10. Richard's reign ended in rebellion, overthrow and death.

Dysentery also killed Henry V, hero of Agincourt, while campaigning in France in 1422. Henry VI became king at nine months old.

The adult Henry VI was utterly unsuited to medieval kingship and was subject to catatonic fits. France was lost and rebellions sparked the Wars of the Roses, which wracked England until 1485.

But in ending John's life when it did, dysentery may have had its greatest impact.

Hundreds of thousands still die from dysentery and related diseases in the developing world

Dr Morris says: "Many kings could be, by our standards, cruel but John was cruel, cowardly and a failure.

"But by dying when he did, it meant Magna Carta, which he had rejected, would be reissued.

"By default, his legacy was such a rule would not be repeated, through a document which still symbolises the rights of the subject against the power of a tyrant."

And while dysentery may sound to many of us like a disease of the past, it is still a major killer in developing countries.

The World Health Organization estimates nearly 900,000 people die from dysentery or similar diseases every year, the vast majority young children.

King John: Dysentery and the death that changed history - BBC News

Death of King John: 800 years on

The one town that worships England's worst monarch

King Street in King's Lynn, Norfolk, one town in Britain that remembers John fondly Credit: ALAMY

Chris Leadbeater, Travel writer

19 October 2016

The Telegraph

It had not been going well. In truth, it had been a dreadful 16-year reign, defined by the loss of Normandy and other English possessions on (what is now) French soil – and by the total collapse of relations between monarch and nobility.

Even Magna Carta – since saluted as a fine achievement of the age, a first fire of democracy – was little more than a sticking plaster meant to keep throne and aristocracy from hacking at each other’s throats.

But even by the low standards of the medieval era, King John’s final days were tawdry. At civil war with the lords of his realm, desperately ill, and in financial woe, the ruler who had succeeded the iconic Richard the Lionheart would leave the stage in pain and shame.

And yet, this month, as these events reach their 800th anniversaries, they are being revisited. Opinion has relegated John (not without justification) to a villainous figure on the fringes of the Robin Hood legends. But his demise is a tale worth retelling. And it can make for a journey through some of the most pristine areas of England’s landscape.

Which is why I find myself in King’s Lynn on a rainy autumn morning. Eight centuries ago, John was here, too. By October 1216, he was beset by enemies in Lincolnshire and Norfolk, but had paused in a place where he was enduringly popular.

In 1204, he had granted this town on the River Great Ouse a charter which would be instrumental in its developing into a busy port.

This help has not been forgotten. Earlier this month a bronze sculpture of John was unveiled on New Conduit Street, continuing a trend for fond memorial in King’s Lynn.

John's baggage train is lost in quicksand in the Wash Credit: 2014 Getty Images/Hulton Archive

The Stories Of Lynn museum in the Town Hall displays a facsimile of the charter, as well as the King John Cup – a relic used at feasts in the Middle Ages, hailed as a gift to the town from the man himself. The reality, that this silver-gilt goblet was crafted circa 1340, has not diminished the affection in which John is held.

The King John Cup

The ruins of Newark Castle, Nottinghamshire Credit: ALAMY

The historic quarter of King’s Lynn which surrounds the museum is not so far removed from the safe haven which greeted its champion in 1216. On the other side of Saturday Market Place, the Minster – constructed in 1095 – would have witnessed the king’s progress.

And if other buildings came later – the 15th-century Hanseatic warehouse on St Margaret’s Lane, a base for German merchants; Bank House, an 18th-century money hub on King’s Staithe Square, now a hotel – they owe their origins to the 1204 charter. Beyond this, the River Great Ouse flows to the sea.

The 15th-century Hanseatic warehouse on St Margaret’s Lane

Bank House

John went westward on October 12, 1216 – and into disaster, cutting along the lip of The Wash, the marshy tidal area which still shapes Norfolk’s top edge. At some juncture, his baggage train became mired in quicksand. Chronicles disagree on whether this cost him a few packhorses or the Crown Jewels, but the incident was a humiliation – a symbol of a failing king’s shortcomings.

King John lost the Crown Jewels somewhere in the Wash, according to chronicles

The hoard has never been found, and has taken on a mythical aura – but the setting remains. And it’s glorious. I take the A17 west from King’s Lynn, turn north for Terrington St Clement, then dive into the maze of farm lanes. At one point, I fear I am as lost as John’s treasure – but Ongar Hill Road leads to a gravel car park, and a path through the fields.

And there, finally, is The Wash National Nature Reserve, behind a high sea bank. A welcome sign shows little has changed. “Please note that parts of the Reserve are very dangerous,” it advises. “There are deep pools, creeks and soft mud.” I stick to the path, amid a swirl of bird song, and a distant hum of tractors.

John emerged from the bog 60 miles north-west, at Newark, Nottinghamshire. Dying. He had contracted dysentery in King’s Lynn, and on the night of October 18-19, he succumbed to it. The castle which framed his last gasps is still there, too, looming over the Trent.

The one town that worships England's worst monarch

King John: Dysentery and the death that changed history

By Greig Watson

BBC News

19 October 2016

The ruin of Newark Castle in Nottinghamshire, where John died, possibly in the gatehouse on the far left

It is 800 years since one of England's most reviled monarchs, King John, died from dysentery. BBC News examines how this gut-wrenching condition has claimed the lives of several English kings, changing the course of history.

"Foul as it is, Hell itself is made fouler by the presence of John."

Chronicler Matthew Paris's epitaph reflects the contempt with which John was widely held - but could also be a nod to his unpleasant demise.

His chaotic and disastrous reign came to a heaving end on, or near, the toilet. Or whatever served as a toilet in Newark Castle on 19 October 1216.

By finishing John, dysentery - essentially diarrhoea so violent it causes bleeding and death - may have spectacularly changed the course of English history.

John was blamed for the murder of Prince Arthur, his nephew, who had a better claim to the throne

And it was not the only time it managed to kill a king or set the country on a new course.

"He was a total jerk," says Marc Morris, author of King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta.

"He was loathed by contemporaries as cruel and cowardly.

"Many people think of medieval Europe as a place where anything goes, like Game of Thrones.

"But there were rules, especially about how you treated nobles. John broke these taboos.

"He didn't just kill, he was sadistic. He starved people to death. And not just enemy knights, but once a rival's wife and son."

Medieval sanitary arrangements could be basic, even for the aristocracy in their castles

Losing swathes of inherited territory in France, and then pushing up taxes to fund vain attempts to get it back, alienated his subjects in England.

A reputation for being a sexual predator with the wives and daughters of nobles, along with arbitrary treatment of both allies and rivals, angered the elite.

He annoyed Pope Innocent III so much the pontiff excommunicated John and ordered England's churches closed.

All this led to civil war, Magna Carta and a French prince, Louis, being offered the throne.

A fanciful recreation of John being forced to approve the Magna Carta

But while fighting, John became weak and sick. Travelling from Norfolk towards the Midlands, he halted at Newark and soon after died.

Rumours put his demise down to eating unripe peaches, drinking too much sweet ale or even being dosed with poison from a toad.

Dr Iona McCleery, an expert in medieval medicine, says: "To say John died of overindulgence was a way of criticising his personality. It implies intemperance, gluttony and imprudence.

"To say he was poisoned showed he was hated. Whatever the truth, those writing down history had nothing good to say about John."

Dysentery is caused by parasites in the gut but is also easily confused with other viral and bacterial infections.

Despite civil war King John managed to get a royal tomb in Worcester Cathedral

It is most commonly spread by dirty water or food being contaminated with human waste.

Dr McCleery says: "Dysentery was not necessarily a condition of the commoner. Lots of vegetables were grown in soil fertilised with human waste.

"John had been on the march, fighting a war, under a lot of strain.

"He was probably physically and emotionally exhausted and living conditions on the march can be primitive, no matter who you are."

After John's death the fire went out of the civil war and Prince Louis was chased from England. Stability returned, the Magna Carta took root.

But dysentery was not finished with the fate of England or its kings.

Henry V was poised to become king of France but died on campaign, leaving an infant heir

Edward I, the Hammer of the Scots, died of it on his way to renew war with Robert the Bruce in 1307. His son Edward II lost the resulting battles and Scotland retained its independence.

It may have accounted for Edward, the Black Prince. Famed warrior and statesman, his death in 1376 the year before his father Edward III meant the Black Prince's son, Richard II, would became king aged 10. Richard's reign ended in rebellion, overthrow and death.

Dysentery also killed Henry V, hero of Agincourt, while campaigning in France in 1422. Henry VI became king at nine months old.

The adult Henry VI was utterly unsuited to medieval kingship and was subject to catatonic fits. France was lost and rebellions sparked the Wars of the Roses, which wracked England until 1485.

But in ending John's life when it did, dysentery may have had its greatest impact.

Hundreds of thousands still die from dysentery and related diseases in the developing world

Dr Morris says: "Many kings could be, by our standards, cruel but John was cruel, cowardly and a failure.

"But by dying when he did, it meant Magna Carta, which he had rejected, would be reissued.

"By default, his legacy was such a rule would not be repeated, through a document which still symbolises the rights of the subject against the power of a tyrant."

And while dysentery may sound to many of us like a disease of the past, it is still a major killer in developing countries.

The World Health Organization estimates nearly 900,000 people die from dysentery or similar diseases every year, the vast majority young children.

King John: Dysentery and the death that changed history - BBC News

Death of King John: 800 years on

The one town that worships England's worst monarch

King Street in King's Lynn, Norfolk, one town in Britain that remembers John fondly Credit: ALAMY

Chris Leadbeater, Travel writer

19 October 2016

The Telegraph

It had not been going well. In truth, it had been a dreadful 16-year reign, defined by the loss of Normandy and other English possessions on (what is now) French soil – and by the total collapse of relations between monarch and nobility.

Even Magna Carta – since saluted as a fine achievement of the age, a first fire of democracy – was little more than a sticking plaster meant to keep throne and aristocracy from hacking at each other’s throats.

But even by the low standards of the medieval era, King John’s final days were tawdry. At civil war with the lords of his realm, desperately ill, and in financial woe, the ruler who had succeeded the iconic Richard the Lionheart would leave the stage in pain and shame.

And yet, this month, as these events reach their 800th anniversaries, they are being revisited. Opinion has relegated John (not without justification) to a villainous figure on the fringes of the Robin Hood legends. But his demise is a tale worth retelling. And it can make for a journey through some of the most pristine areas of England’s landscape.

Which is why I find myself in King’s Lynn on a rainy autumn morning. Eight centuries ago, John was here, too. By October 1216, he was beset by enemies in Lincolnshire and Norfolk, but had paused in a place where he was enduringly popular.

In 1204, he had granted this town on the River Great Ouse a charter which would be instrumental in its developing into a busy port.

This help has not been forgotten. Earlier this month a bronze sculpture of John was unveiled on New Conduit Street, continuing a trend for fond memorial in King’s Lynn.

John's baggage train is lost in quicksand in the Wash Credit: 2014 Getty Images/Hulton Archive

The Stories Of Lynn museum in the Town Hall displays a facsimile of the charter, as well as the King John Cup – a relic used at feasts in the Middle Ages, hailed as a gift to the town from the man himself. The reality, that this silver-gilt goblet was crafted circa 1340, has not diminished the affection in which John is held.

The King John Cup

The ruins of Newark Castle, Nottinghamshire Credit: ALAMY

The historic quarter of King’s Lynn which surrounds the museum is not so far removed from the safe haven which greeted its champion in 1216. On the other side of Saturday Market Place, the Minster – constructed in 1095 – would have witnessed the king’s progress.

And if other buildings came later – the 15th-century Hanseatic warehouse on St Margaret’s Lane, a base for German merchants; Bank House, an 18th-century money hub on King’s Staithe Square, now a hotel – they owe their origins to the 1204 charter. Beyond this, the River Great Ouse flows to the sea.

The 15th-century Hanseatic warehouse on St Margaret’s Lane

Bank House

John went westward on October 12, 1216 – and into disaster, cutting along the lip of The Wash, the marshy tidal area which still shapes Norfolk’s top edge. At some juncture, his baggage train became mired in quicksand. Chronicles disagree on whether this cost him a few packhorses or the Crown Jewels, but the incident was a humiliation – a symbol of a failing king’s shortcomings.

King John lost the Crown Jewels somewhere in the Wash, according to chronicles

The hoard has never been found, and has taken on a mythical aura – but the setting remains. And it’s glorious. I take the A17 west from King’s Lynn, turn north for Terrington St Clement, then dive into the maze of farm lanes. At one point, I fear I am as lost as John’s treasure – but Ongar Hill Road leads to a gravel car park, and a path through the fields.

And there, finally, is The Wash National Nature Reserve, behind a high sea bank. A welcome sign shows little has changed. “Please note that parts of the Reserve are very dangerous,” it advises. “There are deep pools, creeks and soft mud.” I stick to the path, amid a swirl of bird song, and a distant hum of tractors.

John emerged from the bog 60 miles north-west, at Newark, Nottinghamshire. Dying. He had contracted dysentery in King’s Lynn, and on the night of October 18-19, he succumbed to it. The castle which framed his last gasps is still there, too, looming over the Trent.

The one town that worships England's worst monarch

Last edited: